Stock Buybacks Aren't Inherently Evil, They're Just Devilishly Abused

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

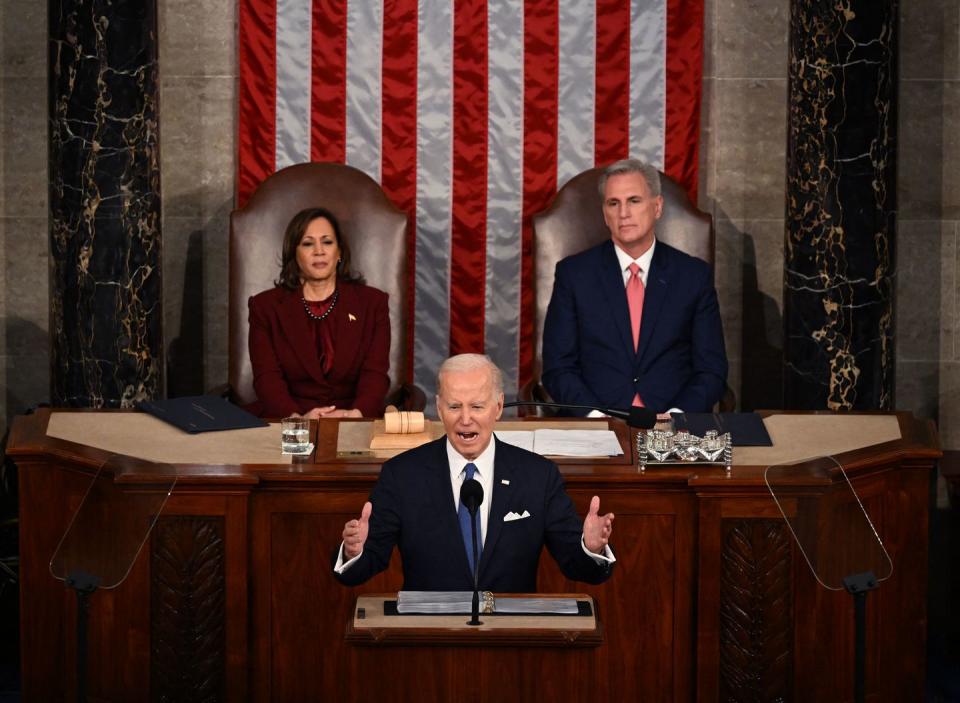

“When you are told that all repurchases are harmful to shareholders or to the country, or particularly beneficial to CEOs, you are listening to either an economic illiterate or a silver-tongued demagogue,” Warren Buffett wrote in his annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders on Saturday. He may be the first man in history to refer to Joe Biden as “silver-tongued,” if indeed Buffett was referencing the State of the Union address. Maybe the president is one for his first category. The Inflation Reduction Act imposed a 1% excise tax on stock buybacks, but in the big speech, Biden proposed to “quadruple” that.

The president also mentioned that the largest oil firms reported record profits in 2022—“$200 billion in the midst of a global energy crisis”—and suggested they had made the crisis worse by not investing in domestic production for years. The oil and gas firms would argue ramping up operations was risky in the increasingly uncertain environment of the last decade, as talk of a clean-energy transition grew louder. But what these firms spent their cash on instead this past year is our issue at hand: “They used the record profits to buy back their own stock, rewarding their CEOs and shareholders,” Biden said. “That’s why I propose we quadruple the tax on corporate stock buybacks and encourage long-term investments. They’ll still make considerable profit.”

If you look at the wider economy, you can see why this made it to the president’s desk. “For the decade 2012-2021,” says economist William Lazonick, who’s written extensively on this phenomenon, “474 corporations that were included in the S&P 500 Index in January 2022 repurchased shares valued at $5.7 trillion, equal to 55 percent of their net income, while also paying out $4.2 trillion in dividends, another 41 percent of net income.” That is, an overwhelming majority of top companies collectively spent more than half of their profits on buybacks, and less than five percent on their workers, building and maintaining their assets, research and development—their business. Not much has changed since 2014, when Lazonick blasted stock buybacks in the Harvard Business Review: Between 2003 and 2012, 449 S&P companies “used 54% of their earnings—a total of $2.4 trillion—to buy back their own stock, almost all through purchases on the open market.”

Like many of the more charming aspects of today’s corporate governance, stock buybacks as we now know them were birthed in the go-go 1980s, the Age of Reagan. Ol’ Dutch’s administration was captured by Milton Friedman and the Chicago School of Economics, and the key pillar of this church was the notion that corporations should be governed on a single principle: Maximizing Shareholder Value. This is, in a sense, the Rosetta Stone for how the American economy got comprehensively fucked over the ensuing decades, but for our purposes here, we should focus on a single obscure policy decision by the Securities and Exchange Commission in November 1982: They rolled out Rule 10b-18, which offered companies that bought back their own stock on the open market “safe harbor” from liability for stock manipulation. (Open market buybacks are different from “tender offers," where all shareholders are presented with an opportunity to sell their shares at the same price and time, often as part of a takeover bid.) This unmanipulation aspect is crucial, because buying back shares often boosts the stock price over the short term. Traditionally, it means the firm is signaling that it thinks its shares are undervalued—they’re a buy. But it also increases the “earnings per share,” a widely used metric for measuring a company’s value.

“It's a sugar high,” says Michael Connor, a former media executive who now leads Open MIC, a nonprofit working to foster corporate accountability. “Everyone feels good for a time, but then it wears off and then you’ve got to do it again and again and again.”

Consider the case of Intel, which became the world’s premier chipmaker through relentless investment in research and development to make its microprocessors not just the best on the market but basically the chip going into any PC. Then it fell off, precipitously, during a period where its then-CEO was forced to admit on an earnings call that the company’s processors hadn’t improved in five years—part of a larger period since 2005 in which the company dumped upwards of $100 billion into share buybacks. They also fell behind Taiwan Semiconductor in manufacturing. Semiconductors are a tough business, because you have to continually reinvest earnings to keep up technologically, but that’s the business. You can’t buyback your way out of that.

This is one of the faults critics attribute to the stock buyback craze: Money goes toward sugar-high share-price boosts in the short term rather than to investments in a more durable company in the long term. It certainly seems to function that way when they’re done to excess, and we have consumed these things like true Americans. The money also has not gone toward higher pay for workers: The four-decade period following the Reagan era saw stagnant real wages for people from the middle incomes down. (Higher up the income ladder, these firms have also often struggled to retain “higher skill” employees over the long term.) Stagnant wages and the explosion of wealth in the top 10, 1, and 0.1% of America—around 10% of the American population owns 80% of the stock—has left us with rampant inequality between those who have wealth and those who get paychecks. Executive-to-worker pay ratios have skyrocketed. And these share-price steroids have allowed some companies to paper over poor governance at the executive level. Look no further than Facebook (Meta) on this one, whose chief executive has overseen stagnation in the firm’s main business, a so-far disastrous pivot to the “metaverse,” a serious round of layoffs, and, soon after those job cuts, the announcement of a $40 billion stock buyback plan.

“You've got one person who is the CEO and the chairman and the largest stockholder in the company, and he frankly is responsible for a number of bad business decisions,” Connor says. “The share price took an almighty hit, and the solution was something close to a gimmick to try and bring it back.” Sears, the erstwhile retailer, represents a kind of combo between Intel and Facebook. Between 2006 and 2017, the firm spent less than 1% of its revenue on capital expenditures—maintaining and improving its existing stores and assets—compared to the 4% Target and Macy’s spent. Those two also bought back plenty of stock, but Sears did $6 billion of them as it circled the drain. The company was eventually stripped for parts to wrap up an entire episode that, despite the demise of the company, greatly benefited its CEO and largest shareholder, a hedge fund vet named Edward Lampert. It’s this kind of stuff that leads critics like Lazonick to call buybacks a tool of “value extraction rather than value creation.”

All too often, buyback campaigns run parallel to rounds of layoffs and benefit cuts. Chunks of the proceeds from sky-high drug prices that pharmaceutical companies say are necessary to fuel innovation are funneled into buybacks. And of course, as Biden mentioned, Chevron and its fellow travelers banked record profits, funneling much of the proceeds into buybacks, while Americans paid surging prices at the pump. The oil firms, for all their uncertainty about their part in our energy future, aren’t really pushing much of the windfall into diversifying their offerings to include more low-carbon technologies. “Clean energy investment accounts for around 5% of oil and gas company capital expenditure worldwide,” says the International Energy Agency, “up from 1% in 2019.”

Buffett backs buybacks as a benefit to shareholders when a company’s share price is trading below its value. However, recently many firms have bought back stock when the share price is cooking. There are times when share repurchases make logical sense, like when a company is trying to fend off a takeover attempt. Or when a company is simply holding too much cash, a buyback allows shareholders (theoretically) to invest that elsewhere. Apple had a giant cash pile in the early 2010s, but its buyback regime quickly got excessive. In 2014, corporate raider Carl Icahn famously wrote an open letter to Apple CEO Tim Cook pushing for the firm to buy back more stock at a time when Cook had already pledged $130 billion in buybacks and dividends by the end of 2015. Meanwhile, Apple had basically no domestic manufacturing capacity. The workers making phones in far-off lands did not see much of that excess cash. Lazonick suggests that big buyback campaigns from the Apples of the world lead to something of an arms race among firms, all looking to boost their prices to keep up.

Alex Edmans of London Business School argued in the Harvard Business Review in 2017 that executives turn to buybacks only after they’ve exhausted other promising areas of investment. He cited…a survey of executives. In the Wall Street Journal last month, Jason Zweig sought to throw cold water on the notion that firms are juicing their stock prices with buybacks, pointing to a study indicating that “in the year of repurchase, companies that did large or frequent buybacks had slightly lower—not higher—returns.” But the same Wall Street Journal reported 10 days later that stock prices have weathered 2023’s tricky economic conditions in part thanks to buybacks. People seem pretty upfront about this stuff on the Street. “Returning value to shareholders” indeed.

Executives benefit to the tune of moral hazard. Not only are options and awards a major portion of any top executive’s compensation, they often earn bonuses triggered by short-term performance. They’ve made a significant bet that the share price will rise over the short term, and they intend to do what they can to see it pays out. “The thing that bothers me the most is when they do stock buybacks but they don't adjust the EPS targets,” says Nell Minow, vice chair at ValueEdge Advisors, a corporate governance consultancy. That’s earnings-per-share. “There are two ways to meet” the targets, she continued. “One is to increase the earnings, and the other is to decrease the number of shares through a buyback. One of those is more beneficial to shareholders than the other…The timing can be, I’m just going to say ‘gamed’ to hit compensation goals.” If firms adjusted their CEO’s targets when a buyback is made, it would remove this incentive.

Minow added that it also grinds her gears when firms borrow money for buybacks—“usually the justification for buying back stock is you've got excess cash”—and when executives “sell into the buyback.” Essentially, they signal to the market that the stock is a buy, then sell it. “If the message they're trying to bring to the market is that the stock is underpriced,” she asked, “Why are they selling it at that price?” Oh, and there was also that time when firms snatched the proceeds from a massive tax cut that was billed as fuel for workers’ wages and capital investment and pumped it into buybacks.

Minow would have executives hold stock for three years following their firm’s buyback. Edmans backed the same in his defense of buybacks in the HBR, contending that repurchases are a sideshow and “giving CEOs pay schemes that incentivize them to hit earnings targets” is the real problem. He would scrap those schemes, while Minow says stock and option awards should be “indexed to the peer group.” If firms want to return money to shareholders in a one-off fashion, they can use a special dividend. (Traditionally, dividends remain at consistent levels year after year.) But now that buybacks have become a regular part of doing business at large corporations, they have a lot more in common with dividends. Not the taxes, though. With the exception of the “qualified” variety, dividends are taxed as income, while buybacks incur no new taxes except for capital gains for investors who sell shares.

Maybe it’s worth revisiting the tax rate on dividends to make them more attractive, because the ecosystem of people who most benefit from stock buybacks is a bit of a murky pool. Dividends reward investors who hold onto stock because they believe the company produces good products and the earnings to match. If a company cuts its dividend with a pledge to push that money into R&D to make more competitive products, and a shareholder doesn’t like it, they can sell. If they hold, they could be rewarded down the road if the company returns to making good products efficiently. But with buybacks, it’s the people selling shares now who benefit. Plugged-in traders can benefit hugely if they figure out when a stock buyback is going to happen, which doesn’t even necessarily imply an exchange of insider information. Minow mentioned executives selling into the buyback, but they aren’t alone.

To enforce new laws of corporate governance, Minow calls on shareholders everywhere to elect board members and candidates for compensation committees who operate on these principles. Lazonick and plenty of others have backed adding workers to corporate boards; they could advocate for some of this whirling windfall to go to workers, and also have a material stake in the long-term future of the company on whose steady paychecks they depend. Minow says anyone who sits on a board needs to have training in how corporations are run, and especially how compensation is awarded. Germany is often held up as a paradigm for worker participation on boards, but Minow contends the workers have suffered for a lack of familiarity with the winding labyrinth of corporate governance.

One thing that everyone I spoke to agreed would not make a difference was Joe Biden’s 1% tax on buybacks. “For some reason, Senators Sherrod Brown and Ron Wyden came out with a 2% tax,” Lazonick says. Through some Capitol Hill politicking, Senator Kyrsten Sinema successfully switched out a measure that sought to close the carried interest loophole, so beloved by private equity and hedge fund executives, for a 1% buyback levy in the Inflation Reduction Act. But even Biden’s proposed quadrupling would scarcely blip the radar, Lazonick reckons. (A separate move from Biden’s administration may have influenced at least ol’ Intel’s calculus, though: chipmakers are applying for government grants to build out their domestic manufacturing through the U.S. CHIPS Act that Congress passed last year, and the Department of Commerce is insisting that applicants “detail their intentions with respect to stock buybacks over five years,” with the clear intent of penalizing applicants planning buybacks.) Lazonick thinks a tax would have to be 10% to make a dent, but he’d really like to see 40%. It’s a never-gonna-happen, but his position is fundamentally different from Minow’s vision of shareholders and corporate boards reining in executive excess.

“Those profits were created by workers who worked hard and expect to have jobs in the future and get higher wages when the company's successful,” he says. “And they're created by us as taxpayers who fund all this infrastructure and investment in the knowledge base.” It’s the old specter of Maximizing Shareholder Value. What do your workers who helped build your company, or the commonwealth they built it in, have to do with anything?

You Might Also Like