How the Stats-Above-Everything Houston Astros Paved the Way for Baseball’s Demise

When Jeff Luhnow took over as general manager of the Houston Astros in December of 2011, he ripped the franchise down to its studs and rebuilt it into the most data-devoted, norm-questioning club in the history of American professional sports. The guy even hired a literal rocket scientist—Sig Mejdal, who led the analytical team—to join his staff. While the Astros lost more than 100 games in each of Luhnow’s first two seasons with the team, they eventually won their first-ever World Series in 2017. In the two seasons that followed, they won more than 100 games. And in a sport where the draft process is designed to redistribute young talent to the worst teams in the league, Houston’s minor-league clubs won more games than anyone else’s in 2019.

It sure seemed like the Astros had solved the sport. Well, not quite.

Last week, Luhnow was suspended for a year by Major League Baseball and then almost immediately fired by the Astros after the discovery of a complex, multi-year operation of spying on opposing pitchers. The long arc of the data revolution in sports, it turns out, bends toward bending the rules until they break.

***

Baseball’s Moneyball movement began with a shift in player evaluation. In the early aughts, Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane told his team’s old-school scouts, who were obsessed over how tall and how muscular prospects looked rather than how they performed, “We’re not selling jeans here.” The A’s also realized that walks counted just as much as singles—many of the initial analytical discoveries in sports hinge on first-grade-level math—so they valued on-base percentage over batting average. Bean’s A’s figured out which measurables led to winning, and then hammered away at those stats.

Eventually, though, most teams bought into the advanced evalution techniques. (Hell, you can probably do a pretty good job of it now; log onto Fangraphs.com, sort through the right tabs, and you’ll be able to see how valuable every single player is and was, to the tenth of a win.) With that edge all but gone, the next step was to change the way the game was played. As outlined in Travis Sawchik’s book Big Data Baseball, teams began to shift their fielders based on the micro-tendencies of each individual hitter. Since teams now knew where you were gonna hit the ball, hits themselves began to lose their value. Plus, even with the optimization of fielding position, balls in play produce noisy, not-necessarily predictive data points. So, enter the era of Three True Outcomes, a phrase coined by blogger Christina Kahrl to describe events that minimize the defensive role of the opposing team. Batters now want to either walk or hit a home run, and pitchers just want to strike you out. Pesky fielders have become increasingly irrelevant. The 2019 MLB season saw more home runs (1.39 per game) and more strikeouts (8.81) than ever before. Since 2010, home runs have increased by 45 percent and strikeouts by 25 percent. Today, the ball rarely enters the field of play.

So, if everyone knows who the good players are and everyone is trying to do the same thing, then how do you differentiate yourself? You find a way to scientifically and systematically make the players you already have even better. As Sawchick and Ben Lindbergh described in their recent book The MVP Machine, the sport’s next frontier is turning scrubs into starters, journeymen into superstars, and superstars into superduperstars. “Name a data-driven developmental trend in today’s game, and the Astros aren’t just at or near the forefront of it at the big-league level, but they’re also grooming the current roster’s replacements from Triple-A down to the Dominican Summer League,” they wrote. Under the guidance of Luhnow, the Astros polished their pitchers by teaching them how to increase the spin-rate on their pitches and encouraging them to throw more breaking balls. They optimized their hitters by encouraging them to pull the ball—hit it to the same side of the field they bat from because it increases power—and teaching them to raise the planes of their swings.

After six consecutive losing seasons, the Astros finally made the playoffs in 2015, only to miss out again the following season. With player evaluation, tactics, and player development all checked off the list, the only variable remaining was the other team. How could you know what they were going to do? Since effective mind-control technology still remains in its nascent stage, the Astros jerry-rigged their own psyops. As first reported by The Athletic and then confirmed by an official MLB report, during the World Series-winning 2017 season, Houston illegally used a camera in centerfield to relay the opposing catcher’s signs to a monitor behind the Astros dugout. A Houston player would then literally bang on a trashcan to signify to the batter what pitch was coming. As MLB comissioner Rob Manfred wrote in the league’s report: “Generally, one or two bangs corresponded to certain off-speed pitches, while no bang corresponded to a fastball.” The best part: It’s not even clear that it worked! As Lindbergh wrote for The Ringer, Houston’s offensive performance during the 2017 was actually worse at home than it was on the road.

Luhnow himself denies knowledge of the scheme, but the trashcan-banging spy-game is the logical, farcical endpoint of the atmosphere he established in Houston. Unlike Luhnow, Beane was a failed former top prospect—looked great in jeans, couldn’t hit a ball—and he wanted to rewrite the player pathways in a sport that had failed him. Luhnow, though, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and worked at the infamous, efficiency-obsessed consulting firm McKinsey before getting into baseball. In a barely believable narrative twist, Houston’s stadium used to be called “Enron Field,” named after the defunct energy firm that was called “America's Most Innovative Company" by Forbes six years in a row. The innovation, of course, was massive, systematic corporate fraud and corruption. In 2002, the Guardian called McKinsey, who groomed Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling and advised the company on a number of different projects, “The firm that built the house of Enron.” The firm that built the house of the Enron—well, it also helped build the Astros.

Like other elite titans of industry—the bankers trading in credit default swaps, the pharmaceutical companies pushing opioids—Luhnow and Co. also seemed willing to take shortcuts to a better bottom line. “While no one can dispute that Luhnow’s baseball operations department is an industry leader in its analytics,” Manfred wrote, “it is very clear to me that the culture of the baseball operations department, manifesting itself in the way its employees are treated, its relations with other Clubs, and its relations with the media and external stakeholders, has been very problematic.” Former Astros employees have described Houston as a place where numbers on the page were prized over all else. Luhnow and his top lieutenants took the idea of “maximizing efficiency” to an almost absurd, often immoral degree. In 2018, Luhnow traded for pitcher Roberto Osuna, who had been suspended for violating the league’s domestic-violence policy just a month before, despite the protestations of the majority of front-office members. According to Lindbergh and Sawchik, Luhnow also had to be talked out of drafting Oregon State pitcher Luke Heimmlich, a convicted child molester. An anonymous former staffer told them, “They don’t give a shit, to be honest, what people think about them. Jeff’s gonna do what he wants to do.”

And to what end? Luhnow is out of a job, and so are the other operators named in the report: manager A.J. Hinch, along with former bench coach Alex Cora, who was fired as manager of the Boston Red Sox despite winning the 2018 World Series, and former player Carlos Beltran, who was fired as manager of the New York Mets despite only being hired weeks before. The Red Sox themselves are in the midst of their own MLB sign-stealing investigation. While it’s not as if all of the other teams are following the Astros’ lead in the spying department, they are doing everything else. Thanks to this newfound devotion to player development and stat strategy, teams have been way more hesitant to hand out big contracts to stars, depressing earning power across the league. Last year, one-third of the league’s 30 teams lost at least 90 games, many of them in the midst of their own Astros-esque rebuild. And with so many more walks, strikeouts, and homers—over and over again—the game is just less interesting to watch. Want to see dynamic athletes moving in space, doing things with their bodies that no one else can? Baseball offers less and less of it with each passing year.

Not surprisingly, attendance has declined in each of the past four seasons. It dropped by about one million fans to 68.5 million, while 2018 marked the first year since 2003 that total attendance dipped below 70 million. Teams like the Astros have a better understanding of what wins baseball games than ever before, but somewhere along the way they lost track of everything else. The original Moneyball story was so resonant because it’s about a guy fighting against entrenched, conservative tradition, searching for a better way to play a game that means so much to so many people. Baseball doesn’t exist on a large scale—as a profitable industry that would attract the likes of Luhnow—if it’s not something that compels millions of people to spend their free time with it. Except, Luhnow’s Astros have made Moneyball into something way more menacing: a kind of bloodless, unfeeling search for every possible edge that never stops, fans be damned. And in the end, if no one wants to watch—and no one can trust what they’re seeing—then what good are all those wins?

Ryan O’Hanlon is a writer and editor living in Los Angeles. He publishes a twice-a-week newsletter about soccer called No Grass in the Clouds.

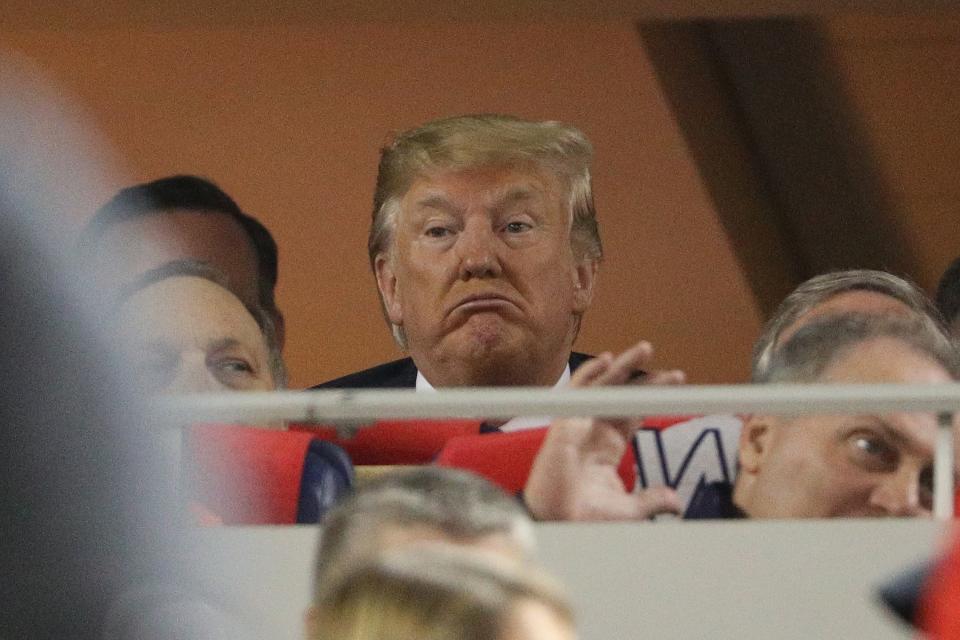

Security confiscated “Veterans for Impeachment” signs that two Iraq War vets unfurled behind home plate.

Originally Appeared on GQ