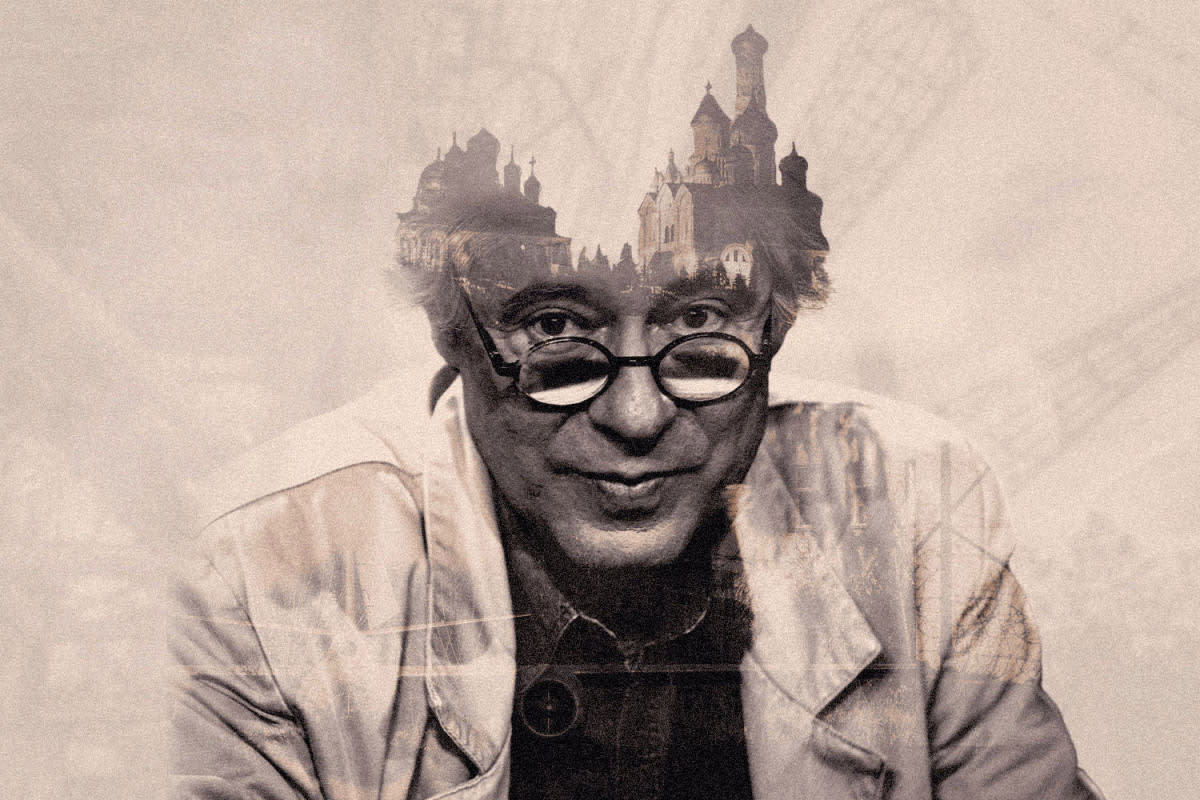

For the Spy Novelist Robert Littell, The Cold War Never Ended

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Two months before the election, I decided to read through the complete works of Robert Littell. They number more than 20 novels, from The Defection of A.J. Lewinter (1973) through to his newest, Comrade Koba, published in November. I had the sense that Littell’s particular style of spy novel would speak to me when American democracy seemed, and still remains, gravely under threat. Where John Le Carre channeled barely suppressed rage into realist narratives steeped in bureaucracy, and Charles McCarry took the adage that “the average intelligence officer is a sort of latter-day Marcel Proust,” Littell is more ironic and mordantly funny than his spy-writing peers, poking an eye at American patriotism while mercilessly skewering Soviet cynicism.

“The Cold War may be over but the great game goes on,” quips a CIA spy to his mentor at the end of Robert Littell’s 2002 masterwork The Company. It is meant as sarcasm, because the 900-page epic documents the on-the-ground, multi-generational, transatlantic horror resulting from the United States and Soviet Union’s bipartisan addiction to spying. But it is also stark truth that cuts deeper almost two decades later: too many people still view geopolitics as sport, the consequences (mass death, propping up tyrants, terrorism, hunger, you name it) barely registering as important.

Littell acquired his espionage acumen as a foreign correspondent for Newsweek in the 1960s, reporting from behind the Iron Curtain on multiple occasions. (His time in Bulgaria led to the 1976 novel The October Circle.) He quit the magazine to write full time and then moved to Paris with his family in the early 1970s, where he has lived ever since. The expatriate remove almost certainly allows for distance from his home country, but it also allows for clarity, as in this essay on the erosion of national security under the outgoing administration.

Littell’s characters are always aware of being pawns. AJ Lewinter is structured like a chess match. Charlie Heller, spurred by the terrorism death of his fiancée to plot revenge against her killers in The Amateur (1981), uses his top-secret cryptography skills to blackmail the agency into letting him run wild, even as they fully intend to exact opposite. The Sisters (1986), my personal favorite of Littell’s novels, is a joyous romp of intelligence hijinks by two ruthlessly intelligent case officers, until the reason for their clever goings-on – a presidential assassination – dawns with mounting dread. And Martin Odum spends the entirety of Legends (2006) grappling with his many identities, stripped away to reveal the hole at the center of his existence, as what must exist for far too many spies, current and former.

Reading through Littell’s body of work brings to mind a quote from Vladimir Nabokov, who knew a thing or two about displacement and reinventing himself in a new language: “Satire is a lesson, parody is a game.” No matter how many revolutions are staged or refuted, how many wars won or lost, how many lives destroyed or obliterated, the fights continue with wearying sameness. The game is never over. There are always new side quests to be countenanced and dispatched of, even as the major one marches forth undeterred.

Espionage is the scaffolding for nearly all of Littell’s books. (There are one-offs, like his second published novel Sweet Reason, a satire-heavy Mutiny on the Bounty homage that doesn’t quite land.) The driving force, though, took me by surprise: I did not anticipate that Littell’s body of work would be so Jewish. Spycraft is the basis for a larger project on the price of assimilation, where the act of becoming someone else, as required when taking on a CIA-produced legend, has roots in the massive waves of immigration coming through Ellis Island in the first part of the 20th century.

This immigration wave directly links to Littell’s own family history. His grandfather, Abraham, arrived in the United States in the 1880s from Lithuania as Abraham Litzky, married Sarah Litowich, and sired three sons, including Leo, born in New York City in 1896. Leo would register for the World War I draft as Litzky, but when he married Sadie Hausman in 1925, he’d altered his name to Littell. His children would bear that surname legally. But the ghost of Litzky, the name left behind on the altar of assimilation, clung to the novelist Robert, the Diaspora Jew and the American expatriate, and surfaces in a number of his books.

That ghost wafts through the The Revolutionist’s Zander Til, an anarchist freedom fighter who organizes strikes on the Lower East Side and succumbs to betrayal (lest he be betrayed) in Stalin’s regime; in the hipster, weed-smoking Rebbe Ascher ben Nachman, “a gondola plying the murky waters between the ultra-orthodox and the ultra-un-orthodox” [p. 13] who chews scenery throughout The Visiting Professor (1994); and in every murdered or missing Yiddish poet in Soviet Russia, whose art lived on for Littell to read, absorb and memorialize in various fictional forms.

Diaspora immigration doesn’t only preoccupy Littell. The State of Israel, and its shifting meanings, take up much of his literary attention. His first book, written in tandem with fellow Newsweek journos Ed Klein and Richard Z. Chesnoff, was a counterfactual novel imagining that Israel lost the Six-Day War. Decades later, Littell co-wrote a book with former Prime Minister Shimon Peres. And Israel-Palestinian relations ended up under the microscope in the chilling The Vicious Circle (2006), a hostage drama of two fundamentalists — one a rabbi, one an imam — who are closer in ideology and personality than either wishes to admit.

Whether in darkly comic or starkly tragic mode, Littell refuses to preach or moralize. The side he takes is the side that holds up all flaws to the light.

It’s quite likely that Comrade Koba will be Robert Littell’s last published work. At 85, he is firmly in the “late style” phase, where the work becomes leaner, shorter, a single movement rather than a grand concerto. Littell doesn’t have to do that anymore. The Company capped the first 30 years of his career with magnificent sweep and brio. Diversions into private detective fiction with Legends (2006) and A Nasty Piece of Work (2013) felt like change-ups to the espionage fastballs of his 1980s work in particular, The Amateur (1981), Sisters (1986) and The Revolutionist (1988).

His most recent run of novels have shifted focus more closely on the key players of the US-Soviet epic struggle, while keeping those players just out of the frame. Young Philby (2012) is about the UK’s most famous double agent and defector — Kim to some friends, Adrian to CIA director James Jesus Angleton, forever looking for moles and growing increasingly deranged after learning of Philby’s betrayal — but his story is told by others. Seeing him through the fictionalized eyes of his first wife and handler, Litzi Friedman, and his spy-friends Donald MacLean and Guy Burgess, accomplishes more than reading Philby’s own turgid memoir, My Silent War (1968), and complements Ben MacIntyre’s splendid narrative nonfiction account A Spy Among Friends (2014), published two years after Littell’s novel but proof that the novelist got a lot about Philby’s early life right.

A similar gambit animates The Mayakovsky Tapes (2016), where the Soviet poet is vividly present, but only through the stories told by four women — lovers, muses, romantic objects of affection — in a single hotel room on the day that Stalin would die. The women were real, and the stories largely true, but the conceit of assembling Lilya Brik, Elly Jones, Tatyana Yakovleva and Nora Polonskaya in a Moscow hotel room, relaxing into their ecstasies and grievances while a tape recorder runs, elevates the novel from mere trifle to something more potent.

The key is the young man responsible for the tape recorder: R. Litzky is supposed to be silent, but sometimes he can’t help himself, interrupting in English when he’s not supposed to let on how well he understands Russian. His late-book confession of his own identity, the lies and misrepresentations, also cloud Littell’s gamesmanship with the reader: R. Litzky — Rasputin as a joke, Robespierre as a reveal — is a fun-house teen mirror version of Littell himself.

Comrade Koba regresses the Littell/Litzky character further in age, to 10, and renames him Leon, after his father. The conceit is that the boy, orphaned by the sudden death of his father and the imprisonment of his mother, is hiding from Soviet intelligence in their very building. He explores and meets an old man named Koba, who has much to tell about the Stalin regime. Leon relays these stories to his best friend Isabeau, a delightful character whose narration betrays her disbelief at what she considers tall tales — especially the prospect that Koba might be Stalin himself.

The novel doesn’t quite work as a single entity: it’s a little too slight, too caught up in subverting the trope of the dying man imparting stories and wisdom to a younger charge. But it succeeds as a capstone to Littell’s career, his decades-long quest to understand the origins of the Cold War, the nature of spying, and his own reckoning with Jewish identity and assimilation. Much as we try to be someone else, we are only destined to be ourselves.

More Like This

The post For the Spy Novelist Robert Littell, The Cold War Never Ended appeared first on InsideHook.

The article For the Spy Novelist Robert Littell, The Cold War Never Ended by Sarah Weinman was originally published on InsideHook.