Spend the Night in Gore Vidal's Ravello Home, La Rondinaia

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Gore Vidal used to gripe that every morning a tourist boat would pass below his cliff-hugging villa on the turquoise waters of the Gulf of Salerno—a vertiginous one thousand feet below, to be exact. He could hear the tour guide announce his name with her microphone, pointing out the house to sightseers, but to his chagrin he couldn’t decipher what they were saying about him. There are many ways the guide could have described the maestro hibernating inside La Rondinaia, his chalk-white abode in Ravello: fiction writer, celebrity intellectual, acid-tongued wit, pro-promiscuity gay icon, occasional talk show brawler, Hollywood screenwriter, collector of bold-faced friends.

No doubt Vidal would have preferred to be remembered as the most astute diagnostician of the illnesses plaguing the American Empire (or the United States of Amnesia, as he liked to call his homeland). Since his death in 2012, I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard friends wish that the patrician sage were alive to shed light on the wild turns of the past decade. It’s as if our own ears are straining across an unspannable void for one last audience with Vidal. Instead we have only the material that writers leave in their wake: the bulk of their literary work.

But there is another way to chart this literary lion’s peripatetic rise. Like Edith Wharton and Ernest Hemingway, Vidal used his private homes as extensions of his outsize personality. They weren’t simply domestic sanctuaries but carefully engineered showrooms for myth building and social maneuvering. “He used his home like a stage set,” says filmmaker and writer Matt Tyrnauer, Vidal’s literary executor. “And he could use it to either entertain or intimidate.”

“La Rondinaia reminded me of the house in Sunset Boulevard,” says Diane von Furstenberg, an occasional guest, of the overall decor, which included well-placed framed pictures of influential friends, impossible to miss from any chair. “It had the feeling of being inhabited by an old star.”

I visited Ravello recently to spend a night in the house in hopes of summoning a ghost. This summer will be the first full season introducing La Rondinaia to the market of private rentals. (In the most coveted months, the cost is roughly $13,000 a night, or $90,000 a week, via the agency In Villas Veritas, says founder Laura Blair.) A consortium of Italian businessmen purchased the home as a tourist sector investment in 2006, and for nearly a decade there were constant rumors of the house reopening as a boutique hotel. Ultimately, the group couldn’t agree on a direction, and eventually two of its members, brothers Vincenzo and Gerardo di Natale, who had made their fortune with an energy company, bought out their partners. According to Vincenzo’s son Gerardo, La Rondinaia had been a source of fascination for his father as a young boy sailing along the coast. The di Natales began extensive renovations in 2016, giving the 90-year-old property a makeover that included ripping up Vidal’s aged carpets, refinishing the floors, commissioning frescoes for the 26-foot-high ceilings, and, according to Gerardo, dismantling many bookshelves. The only room they didn’t touch was Vidal’s study, now under lock and key.

In an attempt to have the last word on his own days, Vidal wrote two extraordinary memoirs there: 1995’s juicy Palimpsest, in which he recounts his fraught childhood as the heir to a political dynasty, his icy relations with Jacqueline Kennedy (they shared an Auchincloss stepfather), and his tangles with the likes of Tennessee Williams. The follow-up, 2006’s Point to Point Navigation, reads like a victory lap in which Vidal, when not bragging or score-settling, recounts the painful loss of his partner of 53 years, Howard Austen (they met on Labor Day in 1950). By the time Vidal died, at age 86, he could boast of having led one of those giant, sprawling 20th-century lives, the kind, to misquote the Bible, that held many mansions. And he owned literal mansions, stretching from the Hollywood Hills to a prime stretch of the southern Italian coast.

Vidal attributed his love of homes to his itinerant youth as the son of an unstable divorcée who would no sooner move into a new home than start eyeing the exit. He also adopted his Southern grandparents’ cogent advice: “Never rent. Buy if you can.” The writer bought his first of four properties at 21, flush with the success of his first novel, the coming-of-age war epic Williwaw. While traveling through Guatemala in 1946, Vidal stumbled upon a crumbling, earthquake-cracked 16th-century convent in the city of Antigua, and he used $3,000 of his earnings to purchase it. In the short time he resided there he hosted glamorous friends (later enemies), including Anaïs Nin, and he was already at work hashing out a number of novels, including The City and the Pillar, arguably the first American novel to deal explicitly with a gay love affair.

Vidal’s interest in expat life in Central America withered when Italy finally opened up following the devastation of World War II, and he sold the house in 1950. The same year, after renting an apartment in New York, he purchased the historic, bucolic Hudson River estate Edgewater, in Dutchess County. The early-19th-century Federal-style house has a grand façade of Doric columns, and along with Austen, his new companion, Vidal decorated much of the rambling interior with furniture borrowed from his friend, the socialite and heiress Alice Astor Pleydell-Bouverie. Edgewater wasn’t simply a country retreat during Vidal’s years of writing for Broadway and Hollywood (credits include the play The Best Man and the screenplay for Ben-Hur). It also served as the launching pad for his political ambitions, with Vidal running for his district’s congressional seat on the Democratic ticket in 1960. (He later claimed that his connection with John F. Kennedy hindered his chances.)

Vidal sold Edgewater in 1969, but he would have vivid dreams about the property for the rest of his life and would often lament letting it go. By that point he and Austen were ensconced in the bohemian world of their new arena, Rome, a city that offered plenty of decadence, history, and young male attention. In effect, Italy provided the writer the geographic equivalent of his status among his countrymen: He was a man apart, a visionary who, failing to be voted into political power, chose to critique its machinations from a distance.

Vidal did not buy a place in Rome, but in 1966 he installed himself at the top of a 17th-century palace off Corso Vittorio Emanuele II that Austen found when he noticed a sign advertising an apartment for rent. The penthouse was a spacious, rickety 20th-century addition with a double terrace that looked out onto the cat-colonied ruins of an ancient temple to Isis. The views, as well as Vidal’s catty cocktail parties packed with visiting artists and entrenched nobility, were legendary.

In 1972 Vidal became the owner of the property that would come to embody his own ego and self-projection, in its exclusivity and extravagance, in its isolation and ostentation. Rondinaia is Italian for swallow’s nest, an ideal name for a house that appears to teeter on a cliff’s edge. Even in the age of the drone, it seems impossible that such a structure exists, with its fluttering balconies, giant rectangular pool, and seven levels of terraced gardens on six-plus acres of vertiginous mountainside. There are different stories about who first discovered the house: Either Vidal visited it during a sojourn in the late 1940s with his playwright pal Williams and later bought it sight unseen, or Austen spotted a newspaper advertisement and visited it twice before giving the thumbs-up. Whatever the case, Vidal plunked down roughly $1.5 million for the enchanted estate, which was commissioned in 1915 by Ernest William Becket, Lord Grimthorpe, the wealthy owner of the neighboring Villa Cimbrone (now a grand hotel), and completed in 1927 by his daughter Lucy.

The six-bedroom concrete and stucco fortress with high, barrel vault ceilings is only a 10-minute walk from Ravello’s center square. After you’ve gone through three separate iron gates, past groves of lemon and olive trees and gardens of blue hydrangea, and along an allée of cypress trees dotted with Romanesque benches and stone lions, the house finally shimmers into sight. So does the mind-blowing view of swerving Amalfi coastline, with the nearby town and beaches of Minori glittering far below, and the burnished Tyrrhenian Sea. It may be the most scintillating panorama ever afforded a working novelist. Surely it was as close to the heavens as any writer could hope to reach.

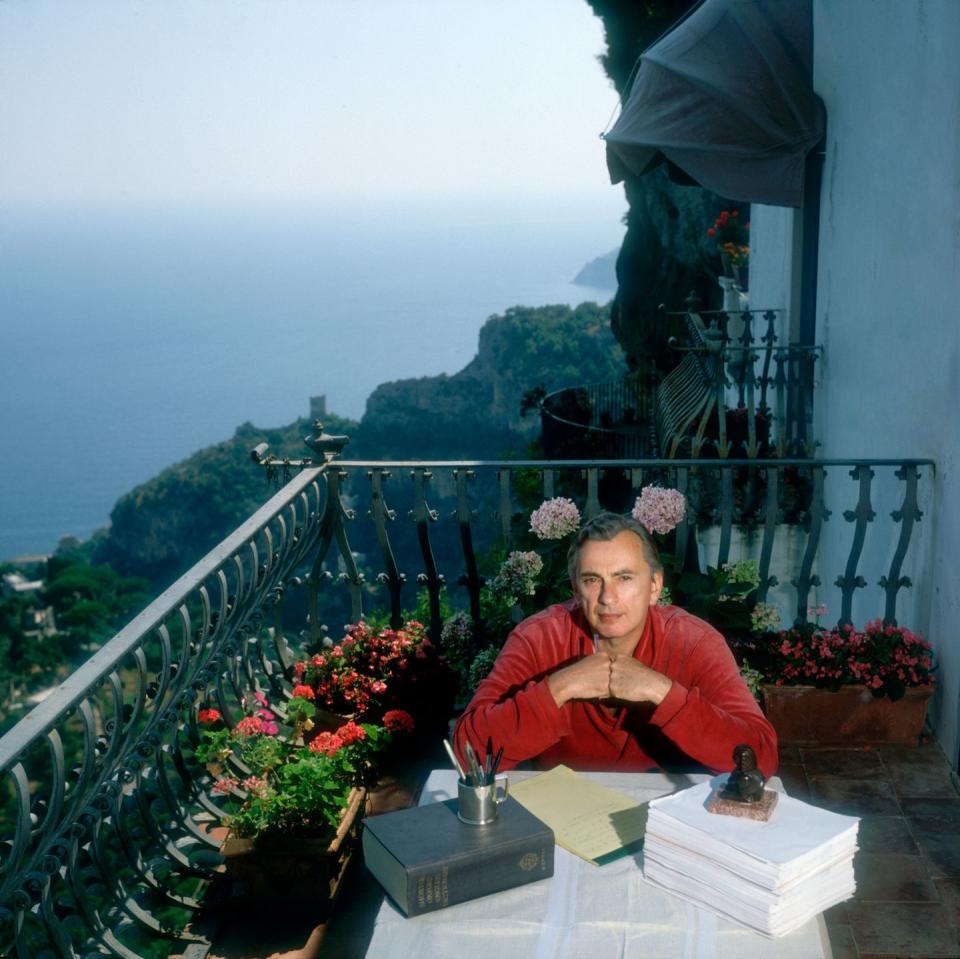

“The house was mythic, and Gore was mythic,” Tyrnauer says. “La Rondinaia would become a big part of his public persona.” He’s right. Many interviews with the novelist were held on his balcony. Vidal used to say that he liked living in Italy because it was the best place to watch the end of the world. It also happened to be a dramatic backdrop for that dying world to watch him.

Initially, Vidal slept in the upstairs bedroom, which was decked in elaborate yellow vietri tiles, but eventually he took the lowest floor for his private quarters. He decorated the larger room with 19th-century American wood furniture from his Edgewater days, mixed in with Neapolitan finds. Austen’s bedroom was next door, separated by a small gym and seating area. That left the airy, sea light–cleaved ground floor for work and socializing. The first room off the terra-cotta and mosaic tiled entry hallway, a white cube, was for Vidal’s study. Inside this bookcase-lined room with a balcony facing the sea, the author wrote every one of his books beginning with the 1973 historical novel, Burr. At his long chestnut desk he would write in longhand on legal pads, later typing up his manuscripts on portable Olivetti typewriters. His work hours were roughly 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., when he would knock off for cocktail hour, an important Vidalian ritual that continued (often in the town square) until well after midnight.

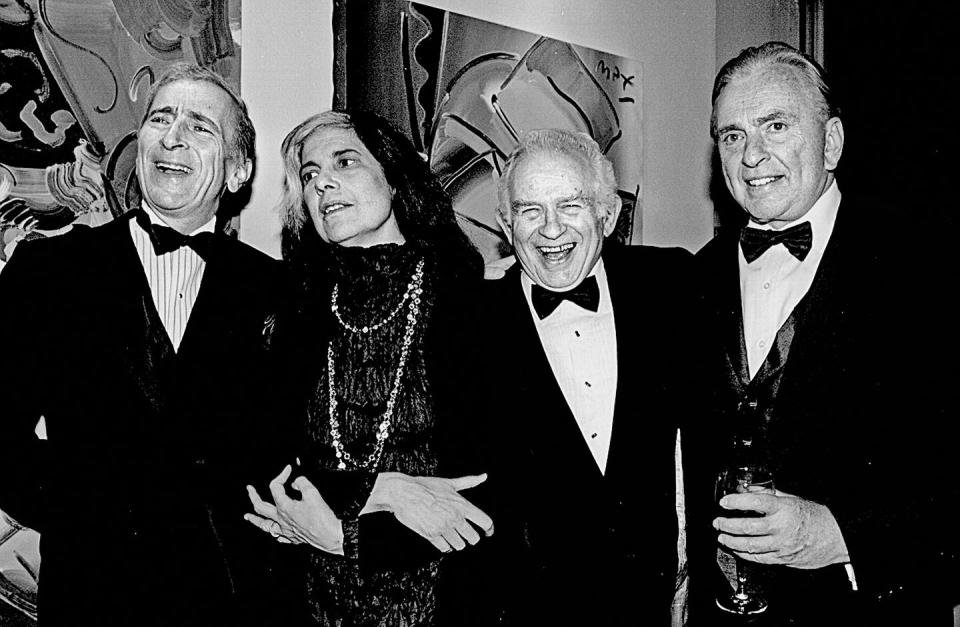

As their Italian years progressed, Vidal and Austen spent more and more time in Ravello; they finally let go of the Rome apartment in the early ’90s. But even in Amalfi they weren’t exactly in exile. One of the paintings that graced Vidal’s study was a figurative work by his friend Rudolf Nureyev. The famed dancer lived on a nearby private island, while film director and producer Franco Zeffirelli had a popular villa on the coast of Positano. (Together these houses formed “the golden triangle” among gay men and in-the-know socialites.) Particularly in summer, high-profile friends vacationing along the coast would stop in for a visit. Over the years, the guests included Mick and Bianca Jagger, Princess Margaret, Hillary Clinton, Paul Newman, Susan Sarandon, Andy Warhol, Carolina Herrera, and Johnny Carson.

Von Furstenberg would hike up the jagged hillside to see Vidal when her yacht sailed along the Amalfi Coast in the summer. “He was incredibly intelligent and witty,” she says. “And he was always nice with me. But his humor could be the kind that sometimes made someone suffer. I think he always wanted to be a politician, and there was a side of him that was a frustrated politician.” One name not on the visitor list was Vidal’s stepsister-once-removed Jacqueline. They were not on speaking terms by the time the writer bought the house, and though she visited Ravello, she never visited Vidal.

From the mid-1990s into the new century, both Vidal and Austen were in regular need of medical attention. On more than one occasion the young men of the village of Ravello were relied upon to carry Austen or Vidal out of La Rondinaia and down to the square, like a human ambulance, during a health emergency.

Vidal’s drinking increased so precipitously as he aged that the same townsfolk were often needed at night to carry him from the local café back to his house. He even had a door installed from an outdoor walkway to his suite, purportedly so that the locals could dump him inside after a rough bender. In 2006, after Austen’s death, Vidal sold La Rondinaia, and most of his furniture was crammed into a Spanish-style mansion in the Outpost Estates area of the Hollywood Hills, the same framed portraits of starry friends set on tables in a smaller studio, his view now a lush interior garden—picture-perfect for a Hollywood legend but by no means the sky-perch of old.

It was there in 2006 that I met Vidal, who smirked from his wheelchair while his enormous orange cat clawed my legs and nearly drew blood. “Do you miss Italy?” I asked him. “No,” he said, unsentimentally. “I had the best of it.” I thought of this visit this spring as I walked into his study at La Rondinaia. Amazingly, most of the belongings were exactly as the writer had left them, right down to a stack of Swiss bank checks made out in his name, a vintage globe, and a few bottles of liquor on the corner of his desk (perhaps the most well-used tools of the writing trade after his four Olivettis).

That evening the weather worsened, and I slept in his bedroom (though not in his bed; the di Natale brothers have gone to great lengths to furnish the house for those with wealthy expectations). I spent those hours in the night trying to channel Vidal by reading through his memoirs. The thunder outside turned ferocious—an angry Vidal, I decided, warning me off his turf. My eyes fell upon an exchange in Point to Point Navigation between the writer and his dying partner.

“Didn’t it go by awfully fast?” Austen remarks, and Vidal answers, “Of course it had. We had been too happy, and the gods cannot bear the happiness of mortals.”

This story appears in the Summer 2022 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like