After My Son Killed My Baby Girl, I Had to Accept Him for Who He Is: A Predator

I hate football. And I really hate Super Bowl Sunday. It was February 4, 2007, shortly after the Indianapolis Colts beat the Chicago Bears, when three policemen knocked on the front doors of Buffalo Wild Wings, where I worked. They spoke with my manager, then they headed over to me.

One officer sat me down and explained that something had happened to my 4-year-old daughter, Ella. I started yelling at him to take me to her.

"No, we can't," he said. "Ella has been killed."

I fainted. When I came to, I asked if my eldest, my 13-year-old son Paris, was okay.

"No, he's alive and at the police station but you can't see him because he hasn't asked for you," said the officer.

"What the hell are you talking about?" I said. "I'm his mother, for God's sake. Take me to him!"

"Ma'am, we can't do that. Paris was the one who murdered Ella."

I lost both of my children that Super Bowl Sunday. Paris was arrested and, 6 months later, sentenced to 40 years in prison. He's at the Ferguson Unit in Madison County, Texas, where I visit him every two or three months and where he'll likely remain well into his 40s.

You could say I was "wild" growing up in Atlanta. By the time I was 17, I was strung out on heroin, and I'd continue to struggle with addiction for years. I graduated from high school with honors and went to college at the University of Tennessee to study human ecology, which, looking back, is ironic.

What makes people work and what makes them tick has always fascinated me. I am of the opinion that in order to understand a person, you also have to understand the context or the environment in which they grew up.

I got sober, but it became harder and harder to live with nothing to take the edge off. I contemplated overdosing to end my life, but then, during my sophomore year of college, I found out I was pregnant with Paris. I finally had something to live for, something to look forward to, and I learned how to be happy.

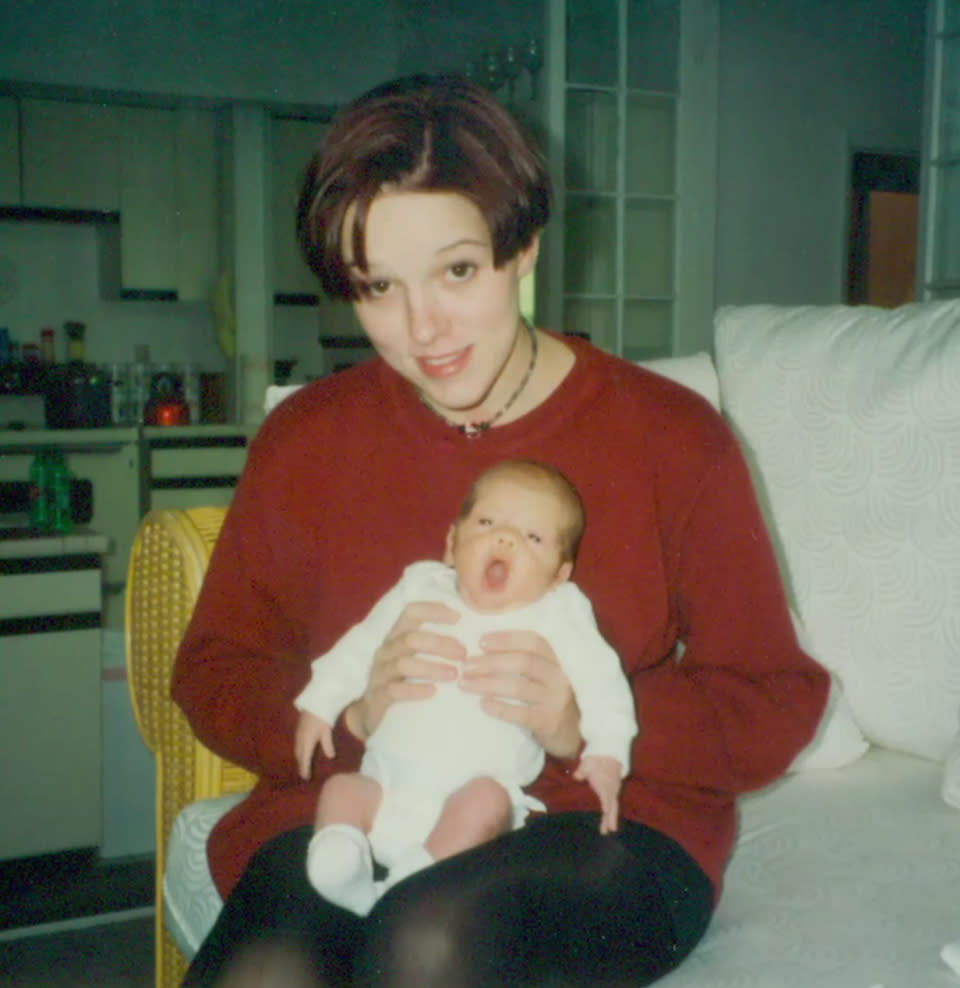

He was a beautiful baby. I remember feeling the deepest love you could imagine when he was born in October 1993. I thought to myself, he is my first born, my first love.

His father wasn't around much, but when he came to visit Paris at 16 months old, it became clear to me that something was very wrong with him. That year, we found out his dad was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. For our child's sake, I decided to cut off contact with him.

I worked odd jobs to support myself through school and relied on financial support from my family. My mother babysat when I needed help. I was young, newly sober, working, going to school, and I felt like my life was based on a lot of conditions. It was a chaotic time.

I graduated from college with my human ecology degree, with a concentration in child and family development. In the following years, I'd meet Ella's father and get pregnant again. I gave birth to Ella naturally, at home. When I first held her, I had an overwhelming sense of protective love and pride for my little girl.

Posted by The ELLA Foundation on Thursday, August 18, 2011

Paris loved Ella too. How could he not? She was an introvert, but extremely opinionated, strong-willed, confident, and goofy. She was obsessed with Ice Age and insisted on watching the same scene - the one where the characters go down an ice-slide - over and over again. Paris and I would just watch her and say my goodness, how many times can she do this?

We were living with my mother in Seymour, Texas, when I relapsed on cocaine for a 6-month-long period. Paris was 11. Even though I wasn't using daily, he stepped up to take care of Ella. Paris was an incredibly smart child. He was artistic, creative, and he never displayed violent or disturbing tendencies, until one day in 2005.

I never, at any point, had any indication that he could kill.

Ella and her aunt, my sister, were playing with a stick outside. Paris took it from them, and when they demanded it back, he destroyed it. The girls were very upset, so I told Paris to go inside. He huffed and walked away. The next thing I knew, my mother's housekeeper ran in and told me that Paris had run off with a knife. We chased him down the street, cornered him, and he started sobbing. He dropped the knife and fell to the ground. We took him to a private hospital.

He was held there for a week. When I called and asked what was happening with him, I'd get no response. I decided to bring him home, and he seemed okay. Of course, we had our issues: He was a teenager and I was maintaining sobriety, but Paris never threatened to hurt me or anybody else. I was honestly more worried about him hurting himself. I never, at any point, had any indication that he could kill.

Then, on that Super Bowl Sunday of 2007, all hell broke loose. I was running late for work and Ella was in the bathtub, under the supervision of a babysitter. She asked me to kiss her goodbye.

"Just one more kiss, momma, just one more time!" she pleaded.

I kept kissing her goodbye. It's my last memory of her.

Paris was pissed off at me. He'd just spent his entire allowance on t-shirts and shoes at the mall, so I scolded him. I was trying to teach him about budgeting. He was sulking in the corner when I left, but I kissed him on the cheek, nonetheless, and told him, "I know you're mad at me but we'll get through this."

Then, around 4:30 p.m., I went to work.

That night, the babysitter left our home without my consent. In her absence, Paris beat and attempted to strangle Ella. He ultimately stabbed her 17 times with a knife. She died, but not quickly, as I'd later find out. And after he murdered Ella, Paris called 911 on himself.

When the officers arrived at Buffalo Wild Wings to deliver the news, a police chaplain offered to drive me home, but I refused. I drove myself. At home a flood of cop cars had already arrived and the media was starting to surround me. I waited in front of the house, freezing, for officials to bring Ella outside.

Finally, after 6 hours, the coroner took her away. She was in a body bag that was zipped up to her chin and she had blood coming out of her mouth. She had a very large contusion on her forehead where she had been punched. I started screaming: I'm so sorry that I wasn't there. The sun was just starting to rise. Right then, I made a promise to Ella that something meaningful would come out of her death.

Two weeks later, I found myself in the District Attorney's office looking at my son, wondering why he had done this. He had positioned himself in a chair in the back of the room when he looked up at me.

"You used to say that you would never be able to kill anybody unless they hurt one of your kids," he said. "I bet you didn't think it was going to turn out like this."

I was scared to death for him.

The DA wanted Paris to plead not guilty, but what good would that have done him? I wanted to get Paris into a mental institution where he, as a minor, could get help. But the prosecution wanted to make sure Paris was given the maximum sentence. He was given 40 years in prison. First he went to a juvenile center and then, when he turned 19, it was decided during a transfer hearing that he would be sent to an adult prison, where he is now.

"Paris scaled on the moderate range of psychopathic traits."

After his arrest, Paris was diagnosed with conduct disorder, the only personality diagnosis that can be given to a minor. [Editor's note: According to the CDC, conduct disorder is defined as a child that shows "an ongoing pattern of aggression toward others, and serious violations of rules and social norms at home, in school, and with peers."] When he was 15, I hired a psychologist who confirmed he had moderate psychopathic traits, or callous-unemotional traits.

Only once I understood what Paris is - a predator - was I able to forgive him. For instance, if I was swimming in a beautiful ocean, enjoying myself, and a shark came up and bit my leg off, hopefully I would not spend the rest of my life hating that shark. Hopefully, I would understand that sharks are what they are. And, for better or worse, Paris is a shark. If you want to dwell on hating the shark, more power to you, but you're not going to get very far. And in an effort to forgive the shark, you need to figure out what makes the shark work. That's been my mindset since college, when I studied human ecology, and that's how I think about my son now.

In June 2013, I gave birth to my third child, a boy named Phoenix. I met his father after Ella died, but he's no longer in the picture. So, it's just me and Phoenix now. His name symbolizes a new beginning, which suits us just fine. Paris writes letters to Phoenix, which he wants me to give to him when he turns 12 or 13. But I question letting the person who killed my daughter talk to my son. I'll never be comfortable with Paris, and I'll never forget what he did to Ella.

Not long after she died, I started the ELLA Foundation, a nonprofit to prevent violence and advocate for human rights through education, criminal justice reform, and victim advocacy. I'm now a public speaker traveling the country to talk about motherhood, the death penalty, mass incarceration, forgiveness, and empathy.

And while I've learned to forgive Paris, you don't ever fully heal from something like that. You learn to live with it. He could've made 10,000 other choices that night and I'll never understand why he did what he did. My son is a predator, but if I spent my whole life hating him, what good would that do? I can't double guess the past. No one can.

Charity Lee shares her emotional story in The Family I Had, a documentary premiering on Investigation Discovery on December 21.

You Might Also Like