Sister, Can You Spare Some Eggs?

At 22, Arianna W. was certain she wanted to freeze her eggs—one day.

It was 2016, and she was interning at Boston IVF Fertility Clinic, witnessing firsthand the spectrum of ways people were creating families. As a queer woman with hopes of becoming a mother in the future, she knew that her own journey to starting a family, biologically, would likely involve reproductive tech interventions.

For that reason, the idea of donating some of her eggs to help another family with a parallel experience was always in the back of her mind. “I just thought it wouldn’t happen until I was going through my own [fertility and egg retrieval] process,” she says.

Arianna was also acutely aware that, “ideally, I should [freeze my eggs] on the earlier side, and not in my mid- or late 30s,” due to the studied age-related decline in fertility. But its five-figure price tag put the option out of reach.

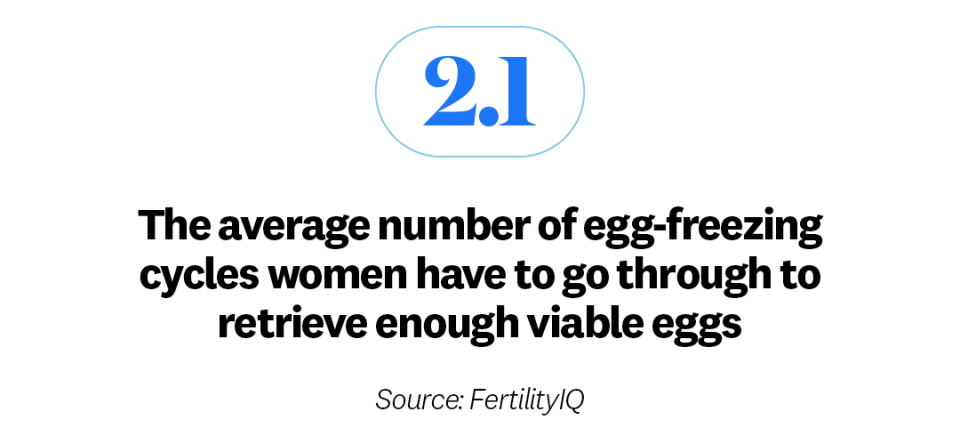

The average total cost for egg freezing is $30,000 to $40,000 for treatment (the average 2.1 retrieval cycles a woman goes through to get enough viable eggs) and storage (for five years), according to data from FertilityIQ, a website that provides courses and information on infertility treatments. “In my early 20s, I didn’t have that kind of money to spare,” she says. “So even though I knew this was something I wanted to pursue, the process was way too cost-prohibitive.”

Seven years later, Arianna was scrolling on Instagram when a compelling advertisement popped up on her feed. The ad was promoting “accessible egg freezing,” including an option to do so for free if she donated a portion of her eggs to another family. Intrigued by this “split” program, Arianna immediately clicked through to begin the process.

The egg freeze-donate hybrid model is a new approach to fertility preservation.

Sometimes referred to as freeze-and-share, this model gives donors the option to freeze a portion of their retrieved eggs in lieu of monetary compensation. So while the donor isn’t offered a cash incentive for their eggs, they don’t have to pay thousands of dollars to freeze and store them, either, and can potentially save themselves an additional retrieval process by doing both at once.

A handful of fertility clinics across the country, such as Oma Fertility and Freeze and Share, offer a version of this approach, with specifics varying between programs.

At Cofertility—a company founded by three women who each experienced their own fertility challenges—the “split” program, which Arianna utilized, is one of the primary offerings. The company also has a program for women solely interested in freezing eggs, and a platform for intended parents to connect with egg donors. The “split” option connects these two groups, giving women the opportunity to freeze and store their eggs for free when they donate half to intended parents who are choosing to use donor eggs due to genetic disease in their family history, or who can’t otherwise conceive, says CEO and cofounder Lauren Makler. That could mean cancer survivors, same-sex couples, or a family dealing with fertility challenges.

With the Cofertility “split” program, women get to keep their eggs frozen and stored for up to 10 years, at no cost. The company says their goal is to break down barriers and challenges that exist in both the egg preservation and donation spaces.

While it may seem widespread in 2023, egg freezing is a relatively nascent technology. It’s been available only since the late 1980s, when it was still considered an experimental procedure. Initially, it was used exclusively for women undergoing cancer treatment or having their ovaries removed—procedures that put their fertility at risk. Then, in October 2012, it was reclassified as an elective procedure by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM).

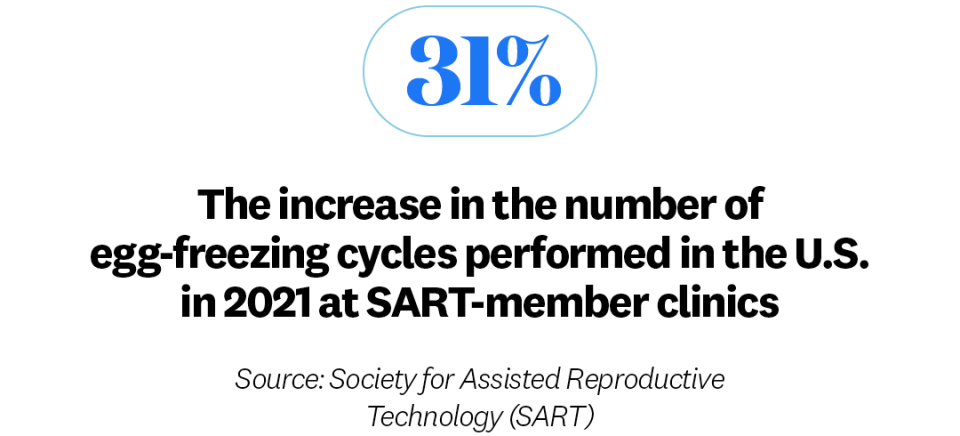

Since that reclassification, interest in egg freezing spiked. In 2021 alone, the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) reported a 31 percent increase in the number of egg-freezing cycles performed at SART-member clinics. Despite its mounting popularity, the staggering cost of egg freezing keeps many interested women from moving forward with this option, especially at a younger age. “Egg freezing, in general, is just something that’s not accessible for most women,” says Makler, “and the best time to freeze your eggs is often when you can least afford it.”

Freeze-and-share models have a different method of attracting clients compared to traditional egg donation programs.

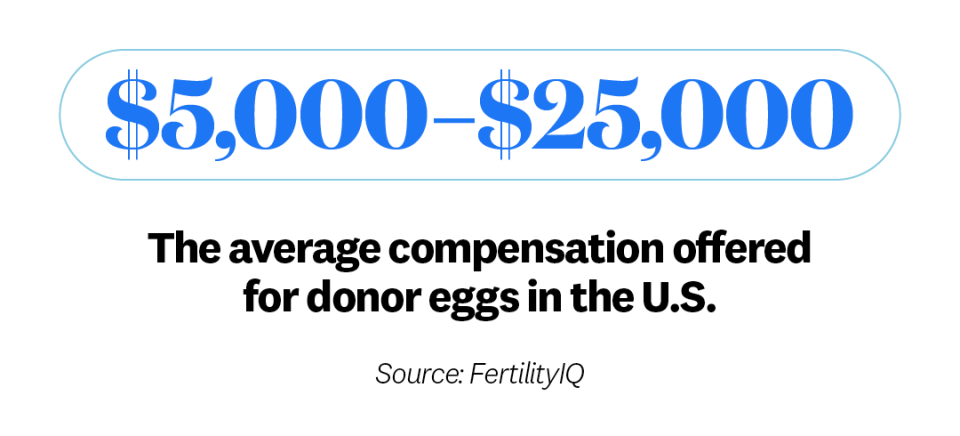

Since assisted reproductive technology (ART) has become more mainstream, donors have typically received monetary payment for their eggs, which the ASRM says is “justified on ethical grounds,” adding, “compensation should acknowledge the donor’s time, inconvenience, and discomfort.”

For the most part, this justification is echoed by clinics throughout the industry, says Lisa Ikemoto, a professor of bioethics and reproductive rights at U.C. Davis School of Law. “The position the clinics have is that they’re not paying for the eggs; instead, they’re paying for the time and effort it takes to provide them.”

But based on many advertisements for donors, and the differing prices offered for eggs depending on the donor, the idea that clinics are simply paying for time and effort “isn’t really carried through, in practice, on a consistent basis,” says Ikemoto.

A simple scroll through social media reveals how some advertisements for donors present the donation process as a fun time. One Meta Ad for the Donor Egg Market bears the tagline “adventure awaits” with the caption: “Egg donors can earn between $50,000 and $55,000 as well as opportunities to travel, all expenses paid, to exciting locations.” Another from Egg Donor Connect Software reads: “Start your egg donor journey today. Reason #5, travel somewhere awesome.”

In highlighting egg donation as a ticket to a vacation, the tone of these ads hardly captures the reality of the process. “It’s important to understand that this is a serious commitment,” says Lauren Bishop, MD, director of fertility preservation and an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

“It involves two weeks of coming into the office for bloodwork and ultrasound appointments, taking nightly injections, and then hopefully ending with an egg retrieval,” Bishop says.

She adds that, while the procedure is generally well tolerated, side effects can include bloating, fatigue, and a full, heavy feeling as a result of the enlarged ovaries. Albeit rare, some more severe potential concerns include ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and ovarian torsion (when an ovary twists on itself).

And while egg retrieval doesn’t impact future personal fertility, according to Dr. Bishop, since it involves removing eggs that would typically dissolve at the end of the month anyway, there isn’t enough research to confirm the long-term effects of egg freezing or donating. Some experts do have hypothetical concerns about an increased risk of breast, uterine, and other cancers—but again, further research is needed.

In addition to highlighting only potential benefits of the process, these types of ads may also motivate someone who isn’t really interested in donating to participate, given the high economic incentive. The issue is “something that has affected mostly women of color who are more likely to be socioeconomically disadvantaged,” says Karenne Fru, MD, PhD, a fertility specialist at Oma Fertility.

While other advertisements, such as one for Donor Concierge, include a more wholesome call to action (“Give a beautiful gift to an unconditionally loving family”), this particular private client ad goes on to offer “$200,000 in compensation to a generous, educated, and athletic young woman.” Which brings up another troubling scenario: the variable cost of eggs based on genetic makeup.

“The industry has demonstrated that it’s willing to respond to racial preferences, [along with] even more class-specific factors that don’t necessarily tell you about an outcome,” says Michele Goodwin, Chancellor’s Professor at the University of California at Irvine and founding director of the Center for Biotechnology and Global Health Policy. (Think: anything from SAT scores to musical talents.)

To an extent, some of these preferences may seem understandable, since most people are hoping their future child will bear a likeness to them. However, while variable costs may boil down to basic economic principles of supply and demand, assigning different values to specific genetics can still be unsettling. “They’re often offered in a way that allows a replication and reinforcement of all kinds of biases. And I think that’s ethically problematic,” says Ikemoto. Based on these practices, she believes the implications are clear: “This is not necessarily about paying people for their time and effort. This is about egg selling.”

Freeze-and-share models are often touted as being more accessible and ethical than traditional egg donation, but experts say there are pros and cons to consider about each option.

The icky feeling associated with this cash compensation model is one of the reasons someone might choose a freeze-and-share program over a traditional egg donation method, despite the fact that they may not get the same high payment they’d otherwise make.

To break it down: On average, egg compensation ranges from $5,000 to $25,000 in the United States, according to Fertility IQ. The average cost for a single cycle of egg freezing, plus 10 years of storage, is roughly $20,500 in the United States, per FertilityIQ. In that case, free retrieval and 10 years of storage, as one would receive at Cofertility, for example, could be considered a financially equitable trade, Goodwin and Ikemoto say.

It should be noted that the average woman needs to undergo multiple cycles of egg freezing to get enough viable eggs for chances of a successful pregnancy later. So, if half a donor’s eggs will go to intended parents (if there’s an odd number of mature eggs, the extra one will go to the intended parents), the donor may want to go through another freezing cycle themselves. This would cost them roughly another $16,000, per FertilityIQ, though a second cycle could also be done through a freeze-and-share program and once again be free.

As mentioned, in the free market, the price tag of donor eggs has seemingly no limit—with compensation as high as six figures and above. So while freeze-and-share is equitable to average egg freezing and storage costs (and may actually be worth more monetarily than some folks would be paid for their eggs), for other donors, it doesn’t compete with the price they could demand.

Based on her own experience with the fertility industry, Makler believes one of the major reasons there is so much stigma around traditional egg donation is the cash compensation model. “It feels really transactional and impersonal for everybody involved,” she says.

In fact, when one 2021 study from Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics surveyed 143 individuals who were donor-conceived, they found “nearly 74 percent said that they often or very often think about the nature of their conception, and 62.2 percent felt the exchange of money for donor gametes was wrong.”

“We think [selling their eggs] is off-putting for a lot of women who might otherwise actually be more than happy to help grow another family,” says Makler. “This stigma leaves intended parents with fewer options, and that especially hurts specific communities, such as LGBTQ individuals, who are relying on egg donation for family planning.”

This stigma was one of the primary barriers for 27-year-old Kristen C., who’s thought about egg donation several times. “My parents are foster parents and one of my siblings was adopted, so I am very familiar and comfortable with the idea of growing your family in different ways,” she says. But the cash compensation model—which made sense to her, based on the time and physical investment—never sat well with Kristen. “Overall, it just didn’t feel right to me, which was weird, because at its core, I felt like donating eggs was such a great thing to do.”

So when she came across the “split” program at Cofertility, it seemed to solve her primary concerns. As a married woman in her 20s, Kristen hadn’t necessarily put egg freezing at the top of her priority list, especially since other financial burdens like student loans and housing took precedence. However, while she and her husband weren’t ready to have kids any time soon, the nagging pressure to figure out her timeline was always looming. “It was exciting for both of us to get the gift of time and to know we don’t have to put so much pressure on ourselves to figure it out immediately.”

There’s also the fact that by removing the cash aspect, programs like Cofertility are able to keep their costs much steadier and potentially lower for intended parents—which increases access in that space as well. With freeze-and-share programs, intended parents are actually paying to cover the donor’s procedure and storage, versus purchasing their eggs.

More transparency between donors and intended parents is also a benefit for some.

There’s another factor to consider with egg donations these days: “True anonymity can be more challenging as hereditary testing and technology continue to progress,” says Dr. Bishop.

With this in mind, Cofertility and Oma Fertility are considering a different approach with their donors that looks much more like an adoption process than an anonymous or impersonal exchange—the traditional model that most (albeit, not all) agencies take.

This means donors and intended parents are matched based on an array of factors. “It could be anything from someone they’d want to be friends with to someone they feel some sort of connection with,” says Makler of the Cofertility program specifically. From there, the intended parents and donors are given the option to meet virtually or in person. Each side has the power to move forward with the process or decide it’s not the right match. They also have the opportunity to outline the type of relationship they’d like to have in the future.

For Arianna, the prospect of a more open agreement was appealing. Her dad was adopted, and he didn’t discover any information about his biological family until his 40s. After seeing the positive impact her dad experienced when he connected with his half sister, Arianna “wanted to give intended parents and whatever biological child an option to reach out or have some sort of connection.”

As an African American woman, it was also important to her to match with a couple “where at least one person was African American. I was also drawn to helping another queer couple in this process,” she says. “Fortunately, there’s a lot of autonomy and flexibility in terms of what this [journey] looks like for each person.”

The matching process has given Kristen a bit more peace of mind too. “Once I met the prospective parents, it was clear they selected me more for my personality than any physical attributes,” she says. “Overall, I’ve felt like I’m valued as a complete person, not just for my eggs—and they’re so happy to help me on my fertility journey as well.”

Though the freeze-and-share option opens doors for many, it won’t work for everyone.

Not all women will qualify as a freeze-and-share donor. At both Oma and Cofertility, women must go through a rigorous screening process in order to be eligible. In some scenarios, a candidate may also become ineligible even after they’ve been matched with intended parents. For instance, at Cofertility, candidates go through further screening (including fertility hormone testing and transvaginal ultrasound). Sometimes, based on the results, “if she is expected to get a very low egg yield, we would not recommend moving forward with the split program,” says Makler.

In cases where the split is no longer an option, donors would have to pay if they wish to continue with their egg freezing. While the costs vary by region, in New York City, it costs $11,000 for a single egg freezing cycle plus five years of storage with Cofertility, whereas Oma Fertility charges $5,500 to $6,000 based on location, with a yearly storage fee of $250 to $500. The donor may also choose not to move forward with egg freezing if the free option is no longer available.

It’s also worth noting that even after freezing and storing eggs, the additional cost of IVF is significant (in the ballpark of $20,000 for a single cycle, per data from FertilityIQ). Plus, “since we can never test for egg quality, it still is a little bit of an unknown if you would be able to get pregnant using these eggs down the road or not,” says Dr. Bishop. In other words, no matter the route, it’s neither completely free nor a 100 percent fertility insurance policy.

These exorbitant prices speak to a larger issue in the fertility space.

While emerging offerings like freeze-and-share programs can be exciting because they “enable more people to access this technology by making it more affordable for them,” says Ikemoto, she wonders if “clinics could also provide greater access across the board by lowering their prices.” When it comes to comparing traditional egg donation with freeze-and-share programs, “the egg-sharing option raises many of the same issues,” Ikemoto notes.

One such issue is the fact that both have the potential to be economically tempting, pushing women who may be on the fence about donation to participate. Not every woman who wishes to freeze her eggs—but is deterred by the cost—is comfortable with the idea of sharing her DNA. In those cases, the options are fairly limited. Although a number of employers offer egg freezing as a medical benefit, the service still isn’t covered by most insurance providers.

“This raises questions about whether there should be access that’s beyond the traditional frames. Should it be through the government? Insurance? Should Medicaid cover it? Is there a human right to the potential to become a parent?” asks Goodwin. “We don’t have that sorted out yet.”

Ikemoto also points out that it’s important to consider who really benefits from these emerging options in the fertility space. At the end of the day, most companies “want to expand their customer base without reducing prices and profitability,” she says. “Egg sharing attracts people, including young people, and leaves the standard price intact.”

Still, there’s no denying assisted reproductive technologies, when folks can access them, can have a profound positive impact. “It has been quite liberating for [intended parents] with fertility challenges, those who aren’t coupled, or who are LGBTQ,” says Goodwin. “This has been a way for many people to create families.”

This article is part of Women’s Health’s coverage of National Infertility Awareness Week (April 23–29, 2023).

You Might Also Like