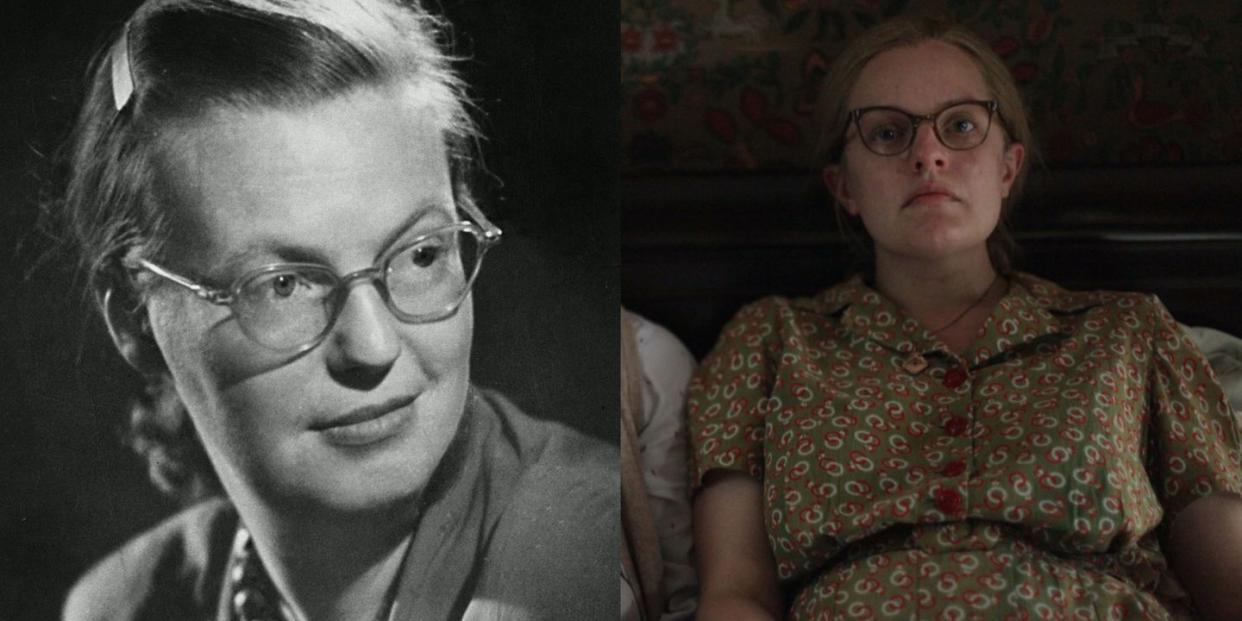

Shirley Jackson Was a Master of Horror. Elisabeth Moss's New Movie Is Only Part of Her Story.

Remember “The Lottery,” that bone-chilling short story about a bucolic New England village where a gruesome ritual sacrifice occurs? For thousands of readers, “The Lottery” is their initial point of access to horror writer Shirley Jackson, as her celebrated story remains a fixture on middle school literature syllabuses around the globe. Yet unbeknownst to many, “The Lottery” is far from Jackson’s biggest accomplishment as a writer; in fact, it’s merely a single dispatch from an American master whose towering life in letters was long under-appreciated.

Jackson has come back into the public eye as the enigmatic subject of Shirley, a sensational new film from indie director Josephine Decker, which stars Elisabeth Moss as the reclusive writer. Adapted from Shirley: A Novel, by Susan Scarf Merrell, the film depicts Jackson near the end of her life, when a young graduate student and his pregnant wife (both fictional) come to stay in her bohemian Vermont home. Fred is an acolyte of Jackson’s husband, the literary critic and Bennington College professor Stanley Edgar Hyman, while Rose becomes something of an amanuensis to Jackson as she writes what will become Hangsaman, her acclaimed 1951 novel. Though Fred and Rose may be fictional, what they observe during their stay are the very real tensions present in Jackson and Hyman’s marriage, as well as the visceral reality of Jackson’s demons.

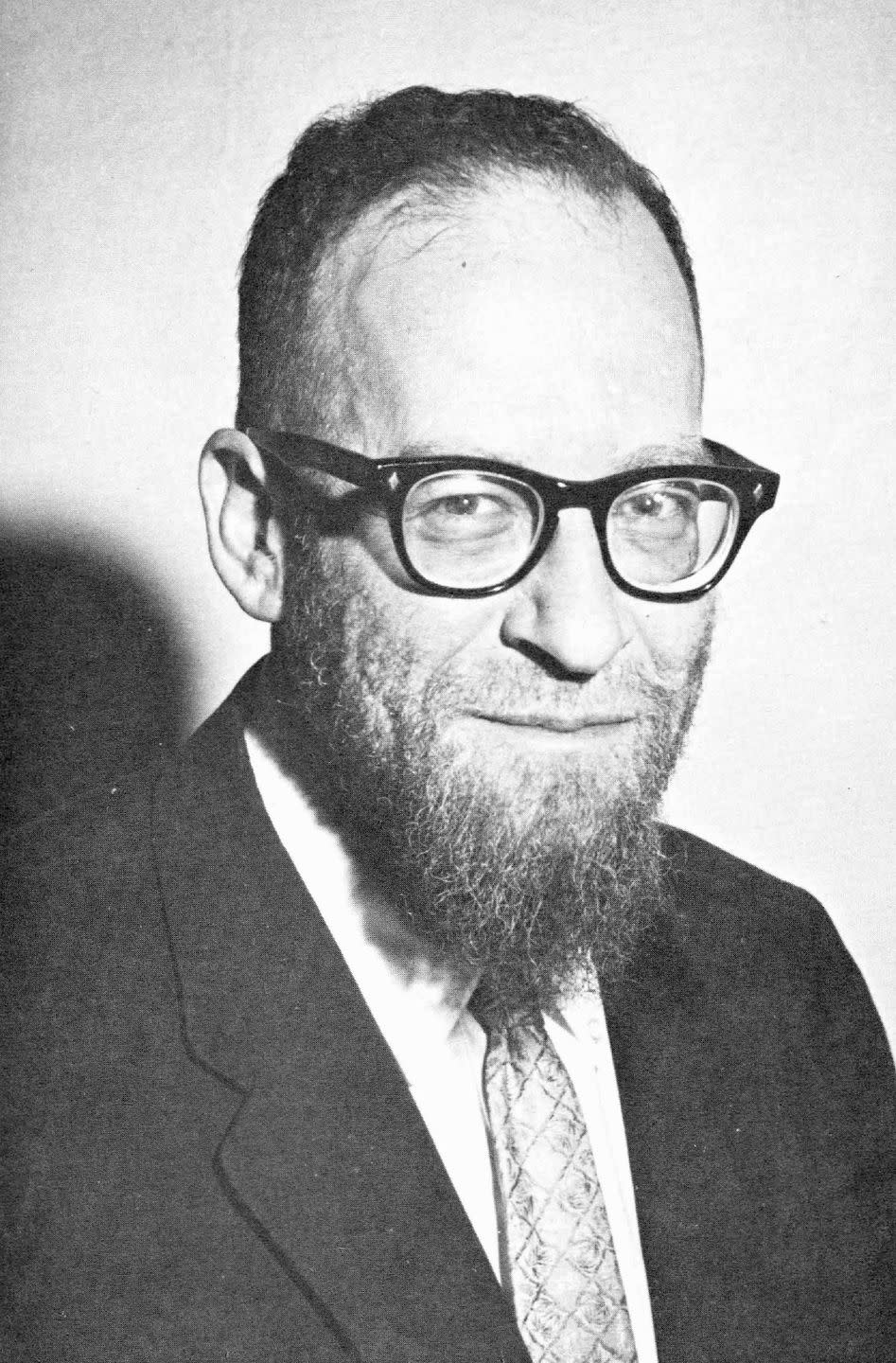

In 1916, Jackson was born in an affluent suburb of San Francisco, where she struggled to fit in with other children and spent much of her time writing. As a young adult, she studied journalism at Syracuse University, where she began publishing her stories in the campus literary magazine. It was through college journalism that Jackson encountered Hyman, who read one of her stories in the campus newspaper and vowed to marry the writer, sight unseen. In 1940, Jackson and Hyman married, traveling the East Coast before settling in North Bennington, Vermont, where Hyman had been hired as an instructor at Bennington College.

Jackson and Hyman became known to the North Bennington community as generous, gregarious hosts, who lived in a rambling home filled with cats, children, frequent company, and over 25,000 books. While their social life was lively and warm, Jackson was miserable in North Bennington, where she felt ostracized by the community (though she had the last laugh, as she modeled the murderous townspeople of “The Lottery” after the people of North Bennington). She also chafed at her role as a “faculty wife,” writing, “I was not bitter about being a faculty wife, very much, although it did occur to me once or twice that young men who were apt to go on and become college teachers someday might … wear some large kind of identifying badge. The way it is now, almost any girl is apt to find herself hardening slowly into a faculty wife when all she actually thought she was doing was just getting married.”

Although Jackson largely enjoyed her role as a homemaker and mother, she turned to the page to express ambivalence about the mind-numbing drudgery of housework, as well as the propensity of domestic life to subsume a woman’s identity. She poured those feelings into a series of comic essays about her hectic life and her cheeky children, which she sold to women’s magazines like Mademoiselle, Good Housekeeping, Woman’s Day, and Ladies’ Home Journal. Those essays later became what Jackson called “domestic memoirs,” titled Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons.

In 1948, Jackson published “The Lottery” in The New Yorker. It generated the most mail in the history of magazine, with thousands of readers sending letters in droves to express their anger and confusion about the story’s disturbing ending, where a woman is stoned to death by her neighbors. Despite the backlash, it became one of the most significant short stories of its time, translated into over a dozen languages and adapted for radio, television, and the stage. The success of “The Lottery” turned Jackson into a literary star, though her growing fame bred conflict with Hyman, who believed fiercely in Jackson’s talent, yet bristled at the degree to which her literary career had eclipsed his own. Though Jackson had become the breadwinner of the family, Hyman maintained financial control, meting out portions of Jackson’s earnings to her as he saw fit.

Jackson was tortured by Hyman’s infidelities, particularly with his students, and by his insistence on regaling their friends with tales of his extramarital exploits. From the early days of their courtship, Hyman insisted on sleeping with other women, browbeating a reluctant Jackson into an open marriage that was decisively one-sided. She expressed her rage through her art, sneaking pompous, Hyman-like men into her fiction while also sketching cartoons of herself serving Hyman entrails for dinner or lurking behind him with a hatchet. It was this tension between a woman’s prescribed role and the psychic damage caused by it that fueled her fiction, populated as it is by women whose psychological demons manifest in supernatural horrors.

In 1959, Jackson published her most celebrated novel, The Haunting of Hill House, which Stephen King called one of the most important horror novels of the twentieth century. Yet by the time of the novel’s publication, Jackson’s health was in steep decline, as she suffered from heart problems, weight-related issues, and crippling anxiety that left her unable to leave the house. Jackson self-medicated with alcohol, amphetamines, and barbiturates—a potent combination whose negative interaction was not understood by the doctors of her time. Shirley depicts Jackson deep in the throes of agoraphobia, with Hyman taunting her about her inability to leave the house. Though she continued to publish even through her bouts of ill health, including her celebrated final novel, We Have Always Lived in a Castle, Jackson died of a heart attack in 1965 at just 48 years old, leaving behind a number of unfinished and undiscovered works that have resurfaced in the decades since.

Shirley takes liberties with the timeline of Jackson’s life, shuffling the years to depict how her psychological turmoil informed her finest works. Though Jackson published Hangsaman in 1951, the film depicts her writing Hangsaman in 1964. Shirley also completely erases the four small children present in Jackson and Hyman’s home, making no mention of parenthood whatsoever. Yet perhaps its biggest leap is the bold eroticism of Jackson’s relationship with Rose, as Jackson’s biographers have found little evidence that Jackson was sexually interested in women.

Despite its looseness with the facts, Shirley’s success is not its faithfulness as a biopic—rather, its success is its illumination of its subject’s extraordinary connection to the psychic damage suffered by the women of the time, who too often felt trapped, alienated, and unmoored from their identities. Jackson’s heroines are manic and feral, forever on the edge of losing their cool, persecuted by what Jackson called “the demon of the mind.”

Literary scholars are still reckoning with Jackson’s legacy, as she was largely viewed in her lifetime as a gothic fabulist, cordoned off into the ranks of “genre” writers whose works are too pulpy to merit serious literary consideration. One critic even went so far as to call her “Virginia Werewoolf.” Certainly Jackson thrived in the horror milieu, claiming to be a “practicing amateur witch” and bragging about the hexes she placed on publishing houses.

Yet in recent years, the literary firmament has committed to reassessing her work, with the post-feminist critic Elaine Showalter arguing that it is the most significant mid-twentieth-century body of literary work yet to be reevaluated. Such reevaluation stands to yield myriad insights about one of our finest writers, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. Ruth Franklin, Jackson’s biographer, puts it best, arguing that her body of work “constitutes nothing less than the secret history of American women of her era.”

You Might Also Like