Seven Mayors, Three Crises, One Text Thread

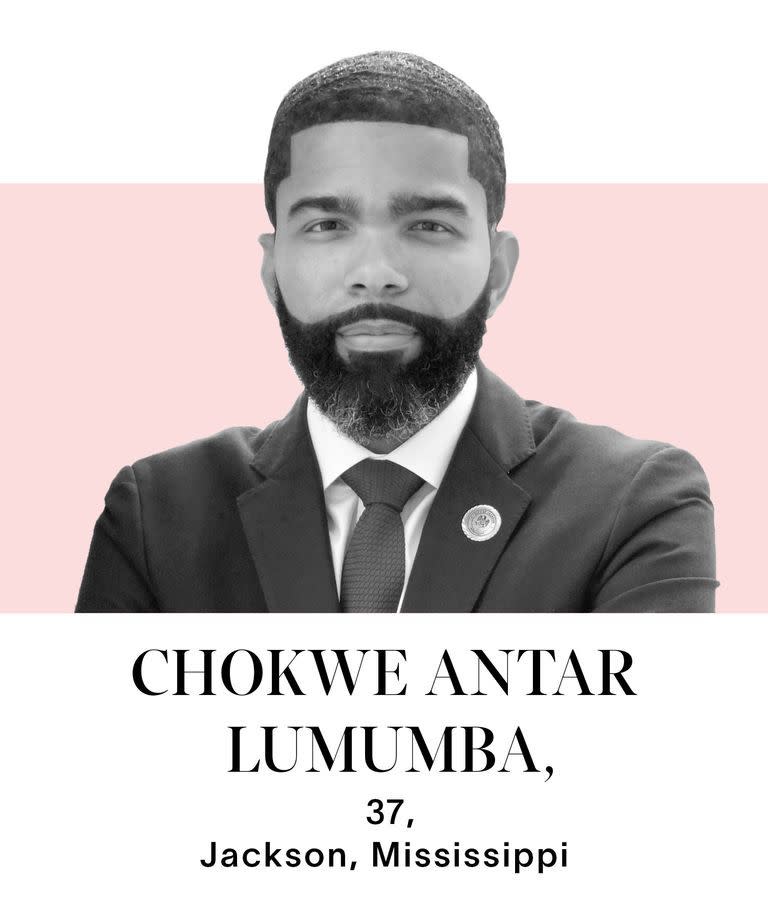

“You see how nice the office is in Montgomery?” asked Chokwe Antar Lumumba, the mayor of Jackson, Mississippi. “You see that? They gave him the Oval Office in Montgomery. You’re on mute, Steve.”

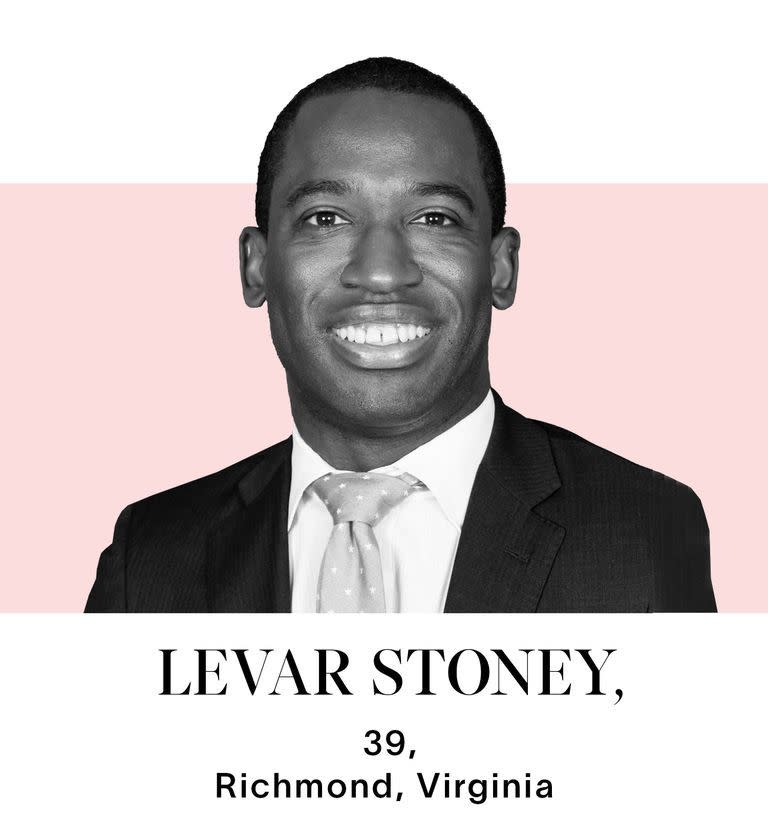

That’s Steven Reed, the mayor of Montgomery, Alabama, whom Lumumba was busy ribbing over Zoom. Reed was not the first to catch some light heat as we waited for the rest of the cohort to get on the call. Mayor Levar Stoney of Richmond, Virginia, was informed moments earlier that he could use a visit to the barbershop. “From my first campaign to my second one, I looked at my old pictures,” Lumumba added by way of consolation, “and I wouldn’t have voted for me.”

He’s got jokes, but Lumumba is also, as Mayor Frank Scott of Little Rock, Arkansas, would later say, “the scholar of our group.” The group in question is an extraordinary one: a network of young Black men—most in their thirties, some in their forties—who serve as mayors of cities across the country, and act as friends and sounding boards to one another. Few mayors in this nation’s 244 years have been hit with the gale forces of history quite like these men have, and the fact is that there are only so many mayors to talk to in the first place. It’s a smaller group still who know what it means to be both a mayor right now and a Black man in America always.

They’ve had the odd phone call through the three crises facing us all—the coronavirus pandemic, the accompanying economic turmoil, and the massive movement for racial justice following the killing of George Floyd by officers of the Minneapolis Police Department—but they primarily operate via text. They’ve got a group chat going, and that’s where they say they turn whenever they’re stumped, need advice, or want to hear a voice that doesn’t have an interest in their local city politics. Sometimes they just need a laugh.

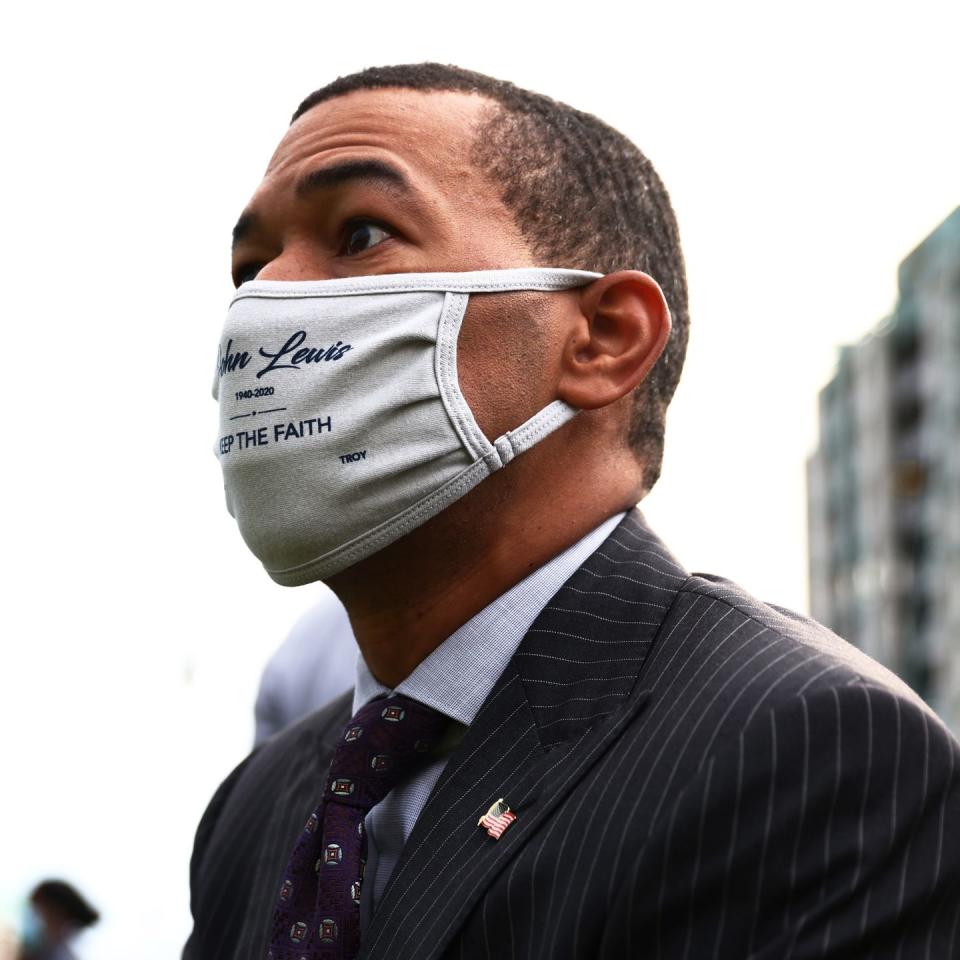

Seven of the mayors in the group were represented here, all from the South except for Quinton Lucas of Kansas City, Missouri, aka “Mayor Q.” Many of the others now lead cities that once served as capitals in the Confederate States of America. They mostly met through the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative and other mayoral conferences. Reed, forty-six, is Montgomery’s first Black mayor; Lumumba, of Jackson, is thirty-seven; Richmond’s Stoney is thirty-nine; and Scott, thirty-six, is Little Rock’s first Black mayor. There was also Adrian Perkins, mayor of Shreveport, Louisiana, who’s thirty-four, and Randall Woodfin, of Birmingham, Alabama, thirty-nine.

They have separate threads going with Keisha Lance Bottoms, LaToya Cantrell, and Sharon Weston Broome—the Black women mayors of Atlanta, New Orleans, and Baton Rouge, respectively—but “this fraternity has been really helpful to me on a personal note,” Lumumba said about the group of male mayors. “My father was mayor” of Jackson, he continued, referring to Chokwe Lumumba, who took his last name from the Congolese independence leader who was assassinated with Western involvement. “[My father] died in office, and I often wonder how he would’ve handled things. And so just being able to bounce things off like-minded people in similar circumstances, it’s just a unique thing.”

“As one of the newer members,” said Perkins, the youngest of the group, “I can attest that as soon as I was elected, I could reach out to each and every one of you and you were all there for me.”

“That’s my same experience,” said Lucas, whose occasional snark can land a beat late behind his dry, declaratory tone. “I went to the U. S. Conference of Mayors this year, which was pretty much my last time out of town. I met everybody and got linked from there. You know, I’m remembering y’all because I don’t get any vacations anymore.”

Back in March, Esquire planned to meet with the group over shrimp at Orlandeaux’s, a Shreveport spot that claims the title of oldest continuously operating Black-owned restaurant in the United States, to talk about the newly elected mayors’ experiences. But then Covid-19 went from over there to right here seemingly overnight, and it was tough for any mayor to leave town. We moved our dinner party to an afternoon Zoom. There was, regrettably, no shrimp.

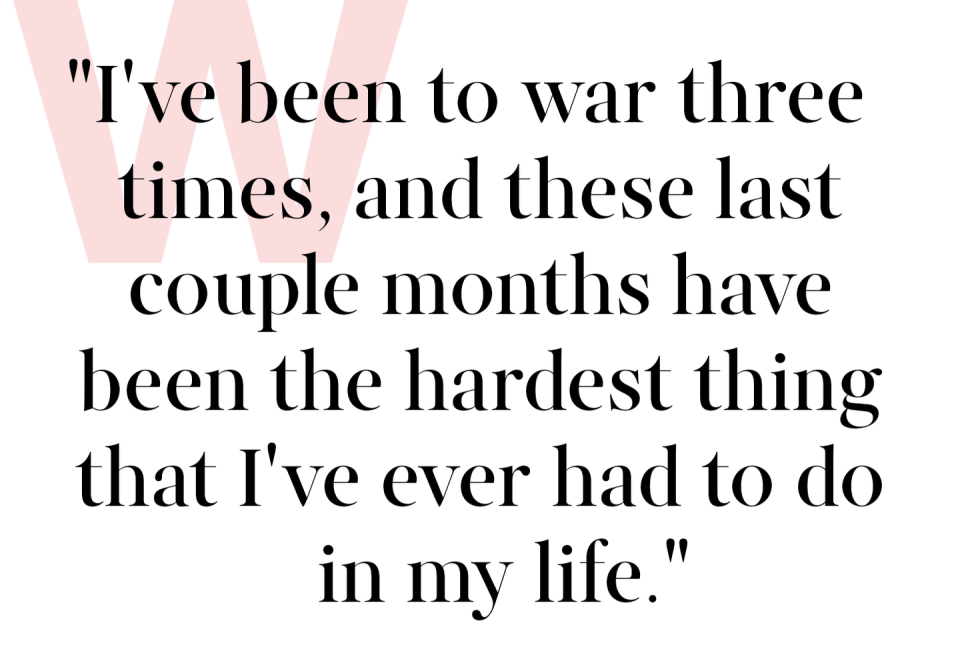

“I’ve been to war three times,” said Mayor Perkins of Shreveport. “I’ve been to Iraq, Afghanistan, and these last couple months have been the hardest thing that I’ve ever had to do in my life. Because we’re juggling three crises. And all of that to your constituents is life and death.

“Our governor just announced on Monday [June 22] that we’re not going to Phase Three, as we’re starting to see an uptick of the virus again. Before, I could focus on the demonstrations, because the virus spread was slowing. Now I’m having to adjust gears again and start dealing with the virus.”

“For us, our protests were relatively peaceful,” said Reed of Montgomery. A former probate judge with an M.B.A. from Vanderbilt, he’s got a bit more of an introvert’s demeanor. He’s not quiet, necessarily, just considered when he speaks. “They were purposeful and passionate. I didn’t have some of the challenges that some of these brothers had in their cities,” he added, referring to, for one, the vandalism in downtown Birmingham the last weekend of May. Montgomery’s most pressing problem was the novel coronavirus.

Alabama, like many southern states, was in the middle of a June surge when we spoke. Eighty-two percent of the state’s ICU beds were already full. The shortage had long been a looming threat in Reed’s jurisdiction, which, like many cities represented here, is also charged with providing services to the surrounding region.

The pandemic mapped onto existing inequities. Seventy-two percent of people testing positive for COVID-19 in Montgomery are Black, Reed said. Ninety percent of people who are placed on ventilators are Black. It was similar in Shreveport. At one point in time in Caddo Parish, where the population is 50 percent Black, 80 percent of COVID deaths were Black people. The disparities extended to who picked up the virus in the first place, too.

When the pandemic hit in earnest, every mayor in America was slammed with a revolving door of decisions. Go into lockdown? When? Can you trust the leader of your state to choose public health over politics? Does the governor have the president in his or her ear saying the cases will soon go to zero? How can you get hold of some test kits? Who needs them first? And how are you going to get your nurses out of trash bags? “We just had a thread going back and forth, because of how fast everything was occurring,” Perkins said. “We just fell back on each other, to really rely on each other.”

COVID-19 is a global disease that operates locally, and mayors have been pressed into service defending their patch against a plague that brought the whole world to its knees. “It can feel just a little bit lonely when you have no one else here who’s going through the same thing inside your city,” said Stoney of Richmond, describing mayoral life but also, perhaps, his slice of the collective isolation of this charming era. To complicate things further, mayors don’t always have the authority to take every action they might want to. Particularly in the Deep South, some cities do not have “home rule,” meaning they aren’t free to make their own decisions on budgets and more. “In southern states, the power is concentrated in the legislature,” Reed explained. “What we’re running into is cities that are primarily led by people of color that are being dictated to by overwhelmingly white and rural lawmakers.”

Sometimes the mayors rely on Republican attorneys general to issue favorable opinions that will allow them to take the actions they feel they need to take, and often those AGs will weigh in with feedback that is more political than legal. “I had an interaction with my AG when Donald Trump came to visit a sister city,” Perkins said by way of example. “He never even stepped foot in Shreveport. And I wouldn’t allow our police officers to go to this campaign event. And our AG was tweeting at me saying, ‘Hey, if you want to learn about the law, I’ll teach you.’ ”

Everyone shook their head knowingly. “Mmph!” Stoney murmured.

“Yeah, I know, right?”

“Adrian,” Stoney said a few moments later, “didn’t you go to Harvard?”

“Something like that, yeah,” Perkins said. “Clearly, I got a poor education according to my state AG, who spelled Louisiana wrong in his campaign commercial.”

I asked whether, as Black Democratic mayors of predominantly Black cities, they feel Republican state officials see them as easy targets for scoring points.

“One hundred percent,” Perkins said. “There’s nothing in it for him to lose, you know? The rhetoric that he has espoused—he’s a replication of our president, and a lot of our state officials are very similar.”

When Mayor Q went to vote in Kansas City earlier this year, he was turned away from his regular polling place on the basis that they couldn’t find him on the rolls. He left without voting. It eventually turned out to be an administrative mix-up that was rectified that day, but most citizens aren’t the mayor and might not go back later to vote, as he did. “A few hours later,” Lucas told me, “the Republican secretary of state in my state, a gentleman by the name of Jay Ashcroft—who makes his father, John, look like Nelson Mandela—said, ‘This was all a stunt and Lucas should’ve just waited.’ I actually took it personally, because that’s what they tell our people all the time, right? You should’ve waited longer; you should comply better with the police. You should do something, even though you were the one who actually was inconvenienced. You need to just be a little more patient. If you complied a little bit better, everything would’ve worked out.”

“Here in Birmingham, we wanted to do a shelter-in-place order,” said Mayor Woodfin, who eschewed the coat-and-tie uniform for a green tee under a blazer and a pocket square to match. He triumphed over seven-year incumbent William Bell in 2017 with the help of Bernie Sanders and Our Revolution. “We did that prior to the state doing it, and I remember the calls I would see from the governor’s office, the AG’s office, and letters telling us we couldn’t do that. I was like, ‘Listen, I have a law degree just like y’all; I wouldn’t recommend something that I couldn’t do.’ ”

Sometimes it’s less a Trumpified governor than the fool next door. The disdain for expertise runs deep in this country, and while the eggheads have made their mistakes, folk science from Facebook usually proves a poor substitute. When Mayor Reed pushed for an ordinance mandating masks in Montgomery during the pandemic, he brought it to the city council, which heard testimony from a procession of doctors at local hospitals before a vote one night in June. Even after they presented evidence of the efficacy of face coverings and how bad the situation had become in the city’s ICUs, the measure stalled, 4–4. One councilman, Brantley Lyons, questioned whether masks and social-distancing measures work and started talking about constitutional rights, prompting calls from doctors in the audience for him to visit a hospital sometime. Reed mandated masks by executive order the next morning.

I asked him whether the vote, in which just one of the council’s five white members voted to mandate masks, had anything to do with how the pandemic was playing out on the ground, landing more heavily on nonwhite communities.

“Absolutely,” he said. “I think that that’s why representation is so important. . . . I think for some of the white council members, maybe their lack of interaction with Black people in this city played a role. Because far too often, when issues hit the Black community, there can be a delayed response, because there’s almost a [need for] justification—of why.

“I had a city council member who, when we were seeing the COVID cases come in, implied that the numbers were so high because they were coming from certain apartment complexes. The places where all these people live on top of one another. Maybe that’s true, maybe it’s not. What does that have to do with us as leaders addressing the issue? Because many of the frontline workers, many of the people who we celebrated, are living in those apartment complexes. They’re the people who are in the pharmacies, they’re in the grocery stores, they’re in the convenience stores, they’re running our public transit, they’re in the warehouses, they’re in childcare and social services. Maybe they don’t have the ability to have a nice house in this subdivision or this suburb.”

In June, the R&B artist Trey Songz, who was born just south of Richmond, called for Mayor Stoney to step down. His call came after Stoney’s appointment of William “Jody” Blackwell as the city’s interim police chief. Blackwell, it soon surfaced, was the subject of a fatal-shooting investigation in 2002. (No charges were brought.) Stoney says he never exactly expected to face the ire of a singer-songwriter, but he does understand. It was the culmination of a tumultuous period for the mayor, which began with him forcing out the prior chief, William Smith, not long after Richmond police tear-gassed peaceful protesters holding a vigil at the monument to Robert E. Lee within the city limits. “We violated [the social] contract,” Stoney told a rally crowd the next day, the Richmond Times-Dispatchreported. He was greeted with jeers. That night, he marched with protesters to the Lee statue, which he now calls “the granddaddy of them all.”

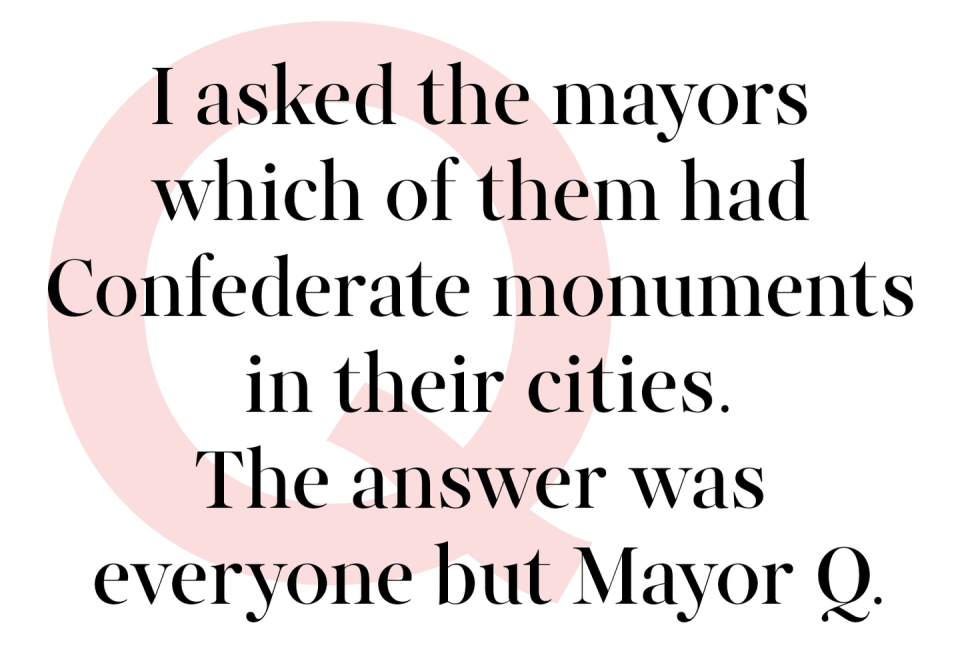

On the Zoom call, I asked the mayors which of them had Confederate monuments in their cities. The answer was everyone but Mayor Q. (He did offer that there was a movement under way in Kansas City to remove from some public works the name of a real-estate developer whose legacy is tied to redlining, a bit of structural racism more closely associated with northern cities like Chicago.) “I have the Andrew Jackson monument, hence my city is named after Andrew Jackson, too,” Lumumba said, referring to the seventh president of the United States, whose record as a slaver and genocidaire the country is beginning to come to grips with. “We’re thinking about changing it to Mahalia Jackson, Mississippi,” he said, grinning. “We don’t have to change the signage of anything.”

These monuments, often constructed decades after Appomattox in periods when white supremacy sought to reassert itself through law and terror, are vessels for an almighty lie: Confederate leaders weren’t heroes but traitors to the United States. By all means, teach the history, and place the statues in museums with proper historical context. But Robert E. Lee has no right to tower over Richmond as he currently does.

It’s not always as simple as issuing an executive order, however, or even passing a city council resolution. Again, the lack of home rule and local control looms large. “Here in Little Rock, we actually got two monuments at the state capitol, but like many other cities, that’s a different jurisdiction,” said Mayor Scott, a tight-end-turned-pastor who wraps up most correspondence with “I appreciate ya.” He intimated that it will be up to the Arkansas legislature to pull them down. “But last Thursday, around 4:00 in the morning—trying to be a little bit discreet—we took down our Confederate monument.” That one, a lone soldier erected in downtown Little Rock’s MacArthur Park during the Jim Crow era, was within his jurisdiction.

“Even though we own our parks, we manage our parks, we fund our parks, and it’s city property,” Mayor Woodfin of Birmingham said, lamenting the power of the Alabama legislature, “they created a law that says we can’t take down statues, even though those statues are on our property.”

“The other problem that I have,” said Lumumba, “is that my Andrew Jackson statue—we own city hall, but the Masons still own space inside it.”

“What?” Scott asked, chuckling incredulously. He wasn’t the only one.

“Yeah,” Lumumba said, smiling himself. “I’d like another city hall. Now I know, looking at Reed’s background, what my office would look like once we buy our own.

“We’re trying to put a statue of Medgar Evers there,” Lumumba added, referring to the Jackson civil-rights activist gunned down in 1963 by a member of the Ku Klux Klan. “That’s who we want out of ours.” In fact, in July the city council voted to remove the Andrew Jackson statue.

Talk of process and jurisdiction doesn’t quite land with every constituent, however, many of whom are done with being told, in Mayor Q’s words, “to just be a little more patient.” To compound the issue, folks who have been locked out of the systems of democracy now have to learn where all the levers and pulleys are in the machine. It’s a problem of political communication that extends to these mayors’ efforts to reform their systems of policing. “Our residents have a hard time understanding that sometimes,” Stoney said, “because they expect their mayors to be, I guess you could say, all-powerful and strong.”

“Yes, mayors get to appoint police chiefs,” Perkins added. “But a step further you have to take is realizing how much power your civil-service board has to put in place whatever policies, whatever cultural changes you want to implement. They can reinstate officers that you want to terminate; they can completely shoot down any punishment that you want to administer.” (Perkins has made a dent where he can, though. In one of his first acts in office, he signed a repeal of Shreveport’s so-called “sagging pants law,” a 2007 ordinance that yielded 726 arrests, 96 percent of which were of Black men.)

“Chokwe,” Perkins asked, “what about the tweets you got about you being the mayor of Mississippi?”

“Oh, yeah,” Lumumba said with a grin. “When there was a lot of focus, and necessarily so, on the uprisings in the prisons in Mississippi and the deaths that were associated, people were hitting my social media and asking me what was I gonna do about my prisons. I don’t have a prison. The one that they’re talking about is two hours away. I tried to explain this, and somebody said, ‘How can’t you deal with it? You’re the mayor of Mississippi.’ And I said, ‘Oh, I didn’t know.’ ”

But beneath the laughs, there is a real tension in play: These are mayors of relatively large cities, tasked with overseeing police forces, but they are also Black men in America. “I have vivid memories of being pulled over for driving while Black, of being profiled for the type of car I drove,” said Woodfin. “So many times that I knew what to do. I knew to turn my car off before the police came up to my car. I knew to have my window down before the police came to my car. I knew that I already had my wallet out so I wouldn’t have to reach for nothing before the police came to my car. I knew to have my hands on the steering wheel before the police came to the car, turn my music off before the police came to the car. I got to that position because I was being pulled over that many times for driving while Black.”

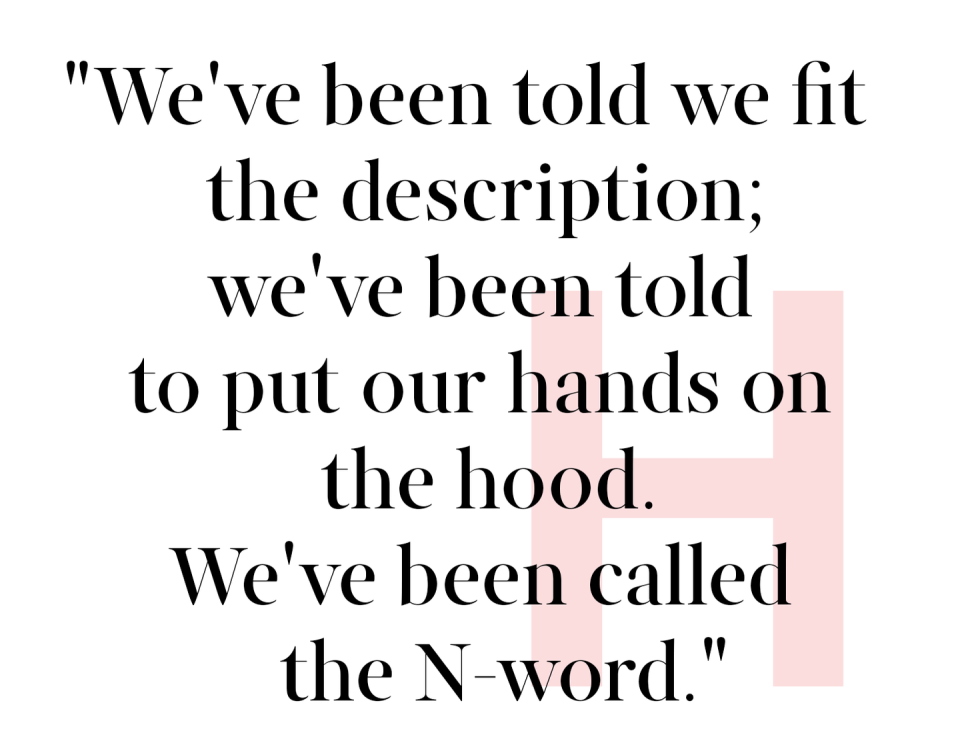

“We’re Black mayors. We’re Black men first,” said Lucas. “We’ve been told we fit the description; we’ve been told to put our hands on the hood. We’ve been called the n-word. My sister lives in Texarkana, and she works in Shreveport”—Mayor Perkins loved to hear it—“and I went down to pick up my niece for the summer, to bring her back up to Kansas City with her grandma. And y’all know this, the fear you have. I’m a Black mayor; I got all these fancy things and all that. I’m just trying not to get stopped in Arkansas. I was like, ‘I might even know the mayor of the biggest city in Arkansas, and that don’t make a difference.’ ”

The gears are grinding into motion. Stoney, beset on all sides for a time by the public he serves, is moving swiftly to institute a system for deploying mental-health professionals as the first responders in certain situations rather than police. He’s working to establish an independent civilian review board to oversee the Richmond force. The interim chief who attracted Trey Songz’s attention has a permanent replacement in Gerald Smith.

Mayor Perkins has put in place regular implicit-bias training in Shreveport along with a ban on choke holds, and his administration has built a website for residents to track progress and hold him accountable. Mayor Scott rolled out his ACT plan—“accountable, clear, and transparent”—which includes a “duty to intervene” policy, requiring Little Rock officers to stop their colleagues from using excessive force.

“Defund the Police,” though, is where the rubber meets the road. Just before I asked about it, Stoney and Reed said they had to hop off the call, the latter announcing he had a meeting next door. I put the question to those who remained: What comes to mind when they hear that term?

“That’s not what you really mean,” Scott said simply.

“The ‘defund police’ campaign in the city of Minneapolis actually started before George Floyd,” Woodfin said. “With the city of Birmingham, there’s a similarity, and then there’s an extreme opposite. The similarity is that they have about 890 officers. We have about 905. But Birmingham’s police budget is $90 million. The Minneapolis police budget is $193 million. In the city of Minneapolis, when they say ‘defund the police,’ I actually think they mean that. I think it’s a literal conversation that they’re having. Ninety-four percent of our $90 million budget goes to personnel costs, meaning if I take any money away, that also means I’m firing police officers, and that’s just not realistic. The notion that we should be doing more things towards social services, I agree with. The notion that maybe certain calls, like if there’s a loose dog, maybe an armed police officer shouldn’t show up—I actually agree with that, too. But I think we have to be very realistic in this conversation.”

“Thirty-five, 45, maybe even 50 percent of our budgets are public safety—our police department and our fire department,” Scott added. “Within those budgets, somewhere between 70, 85 percent of said budgets are personnel, and so when we hear from a mayoral perspective ‘defund the police,’ that means that when someone calls

911, we can’t send someone to you. It’s a catchy marketing phrase, but it has detrimental effects if you actually go forward and do it. What we should be calling for is realigning dollars. Reallocation.”

“When you strip our jobs down, mayors are responsible for two things,” Woodfin said, “public safety and public infrastructure. The reason why our police departments and our fire departments make up the biggest [share of] public works is because no one else is responsible for those things. We think of social services, it’s more of a shared job. It’s not just a city’s tax dollars. It’s nonprofits, it’s the state, it’s the federal government, it’s grants, it’s churches, and it’s private sector.”

“And Rand,” said Perkins, “I’m saying the same thing. I have pennies to throw at the problem with those social services, and that’s why I’m saying, if you really want to have an impact, you can’t rely on that, considering how our budgets are structured and the responsibility that’s laid out in our city charters.”

“And for the record,” Woodfin added, “the emails all of us have been getting from Sydney, Australia, and Canada and these European countries about ‘defund our police’ don’t match what’s on the ground, with Big Mama saying, ‘I want more police.’ It literally doesn’t match.”

“I think about what Big Mama’s talking about,” Lumumba said. “I think about what Ms. Jones is talking about down the street, and the reality in my city is the majority of my police force looks like them, right? So when somebody breaks into their house, they want somebody there. They aren’t talking about defunding the police, because they’re the ones that often feel the brunt of crime more than anybody, right?”

Maybe it’s more than rubber-meets-road. It’s an outright collision of soaring ideals and the harsh realities of running a city every day, of personal experience and public duty. These men want to break the school-to-prison pipeline, but they’re also expected to stop real crime, right now. As the pandemic rages, they’ll have to find a way to get their constituents access to health care. But they also want to get them access to capital. “It’s a moment that lends itself to rising to the occasion,” Lumumba said at another point, “and demanding things that we’ve never seen.”

That’s a lot to tackle over Zoom. Throw it on the text thread.

You Might Also Like