Scribbled notes, classified materials and golf carts: Here's how the millions of White House documents and artifacts should be archived

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

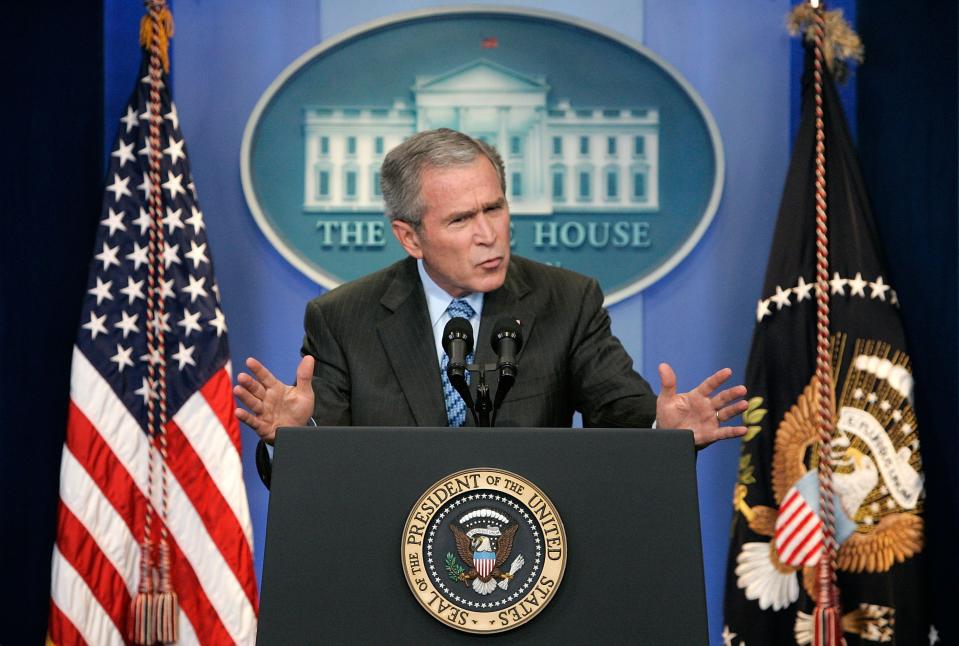

WASHINGTON – By the end of George W. Bush’s eight years in the White House, the quantity of materials needing to be transferred into the control of archivists filled three cargo planes and 25 trucks.

The hundreds of millions of textual, electronic, audiovisual records and artifacts being preserved for history were as mundane as dinner menus and as sensitive as the most highly-classified national security documents. They were as light as a scrap of paper with a scribbled note to Bush and as hefty as the electric-powered golf cart that Daimler Chrysler had given the president during the 2004 G-8 summit.

Former Bush administration officials described to USA TODAY the painstaking process of collecting the items which, by law, were required to be turned over to the National Archives and Records Administration for the benefit of the American public.

Former Obama administration officials sketched a similarly detailed process.

But former President Donald Trump’s freewheeling approach to preserving presidential records led to the unprecedented search of his Florida home by FBI agents this month.

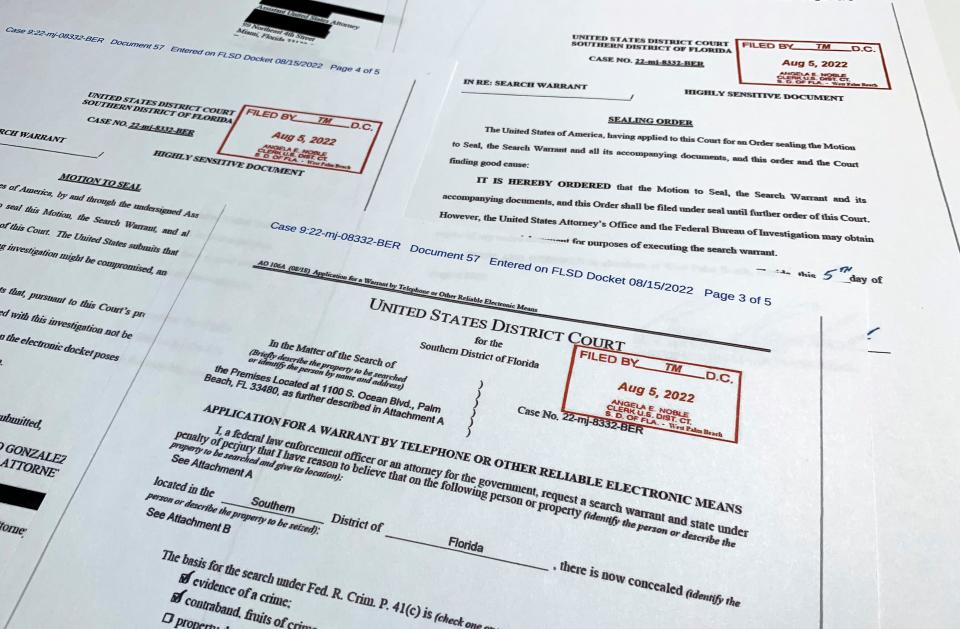

Their retrieval of more than 20 boxes – including 11 sets of classified documents – has galvanized Trump’s supporters in his defense, raised national security alarms, dominated headlines, led to court battles over disclosing what led to the search and could result in criminal charges against Trump or his associates. Even the federal magistrate judge who authorized the search warrant to Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate and is deciding whether to make public the government’s detailed justification, has noted “the intense public and historical interest."

'Can I count on you?': Trump revs up fundraising pitches after FBI's Mar-a-Lago search

Trump responds: Lawyers seek halt of Mar-a-Lago document inquiry, want special master to oversee review

National Archives: the 'nation's record keeper'

The entity representing the taxpayers’ interest in preserving the documents is the National Archives, the “nation’s record keeper,” whose vast holdings include the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, manifests from slave ships and the canceled check from the purchase of Alaska.

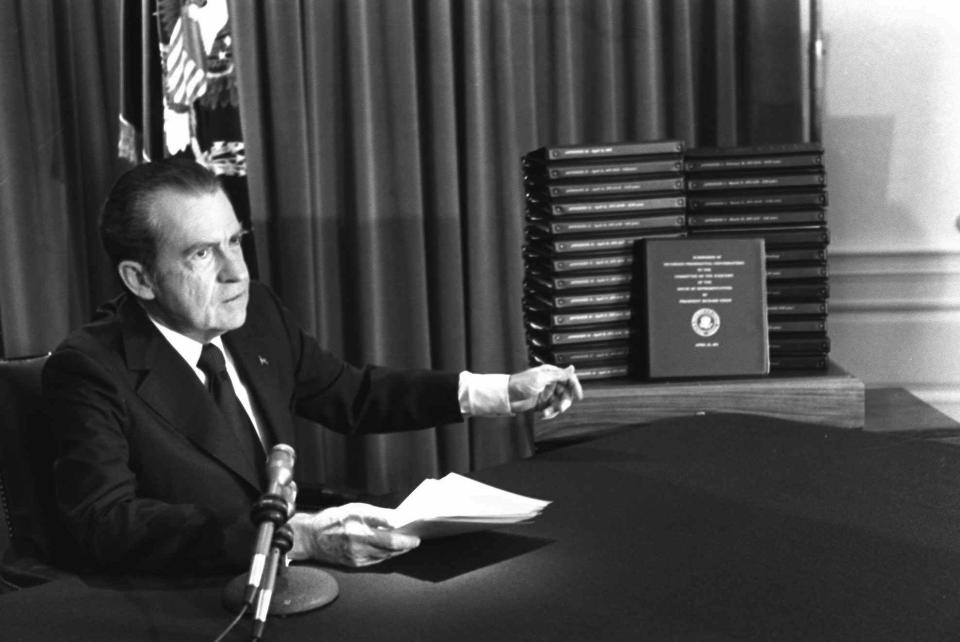

Until the Watergate scandal during the Nixon administration, former presidents owned their records, although some worked with the National Archives to create presidential libraries. But when Richard Nixon, after resigning, wanted to destroy the White House tapes that incriminated him in the cover-up of the Watergate complex burglary, Congress passed a law giving control over presidential records to the National Archives at the end of an administration.

“What this is all about is history and letting the American people know what was done in their names during the course of a particular administration,” said J. William Leonard, former chief of the Information Security Oversight office of the National Archives.

What he said vs. what we know: Trump's relentless attacks on Mar-a-Lago search lack context.

Recap: Judge orders DOJ to redact Mar-a-Lago search warrant affidavit for possible release

Presidential Records Act of 1978

Archivists must sort the files in a way that will make them more accessible to the public. The Presidential Records Act of 1978 gives them five years to do this before historians, journalists and others can request access.

For Ronald Reagan, the first president covered by the act, the National Archives created a computer system to track the movement of records and artifacts as each box was transferred to its control.

The Clinton administration generated the largest number of traditional holdings for his presidential library, with more than 38,000 cubic feet of textual and audiovisual records and 106,000 artifacts, according to the National Archives.

The Obama Presidential Library has the largest set of electronic holdings in the Presidential Library system, including approximately 300 million email messages.

"I don't think the average person is aware of the enormous efforts involved in collecting, identifying and sorting White House records both before and after a president leaves office,” said Jason R. Baron, a professor at the University of Maryland and former director of litigation at the National Archives.

Urgent correspondence: National Archives letter to Trump's lawyers in May outlined urgency of Mar-a-Lago document inquiry

Presidential records are the 'property of the United States'

At the start of an administration, the White House counsel’s office signs off on a directive to staff on how to identify and preserve records.

"At all times, please keep in mind that presidential records are the property of the United States," states the Feb. 22, 2017, memo from Trump White House counsel Donald McGahn II to staff. "When you leave (Executive Office of the President) employment, you may not take any presidential records with you."

Former Bush administration officials, who asked not to be identified so they could speak freely, said they knew from Day One that every email they sent or received would be cached, a thought that was always at the back of their minds.

One said he occasionally added to the end of his emails a joking “What’s up?” note to the person in charge of the digital archiving.

Another former aide who remembers scooping up all his notebooks and turning them in before leaving the White House, said the rules were straightforward and that anything used to do his job was subject to the Presidential Records Act.

As soon as Bush turned away from the lectern after a White House news conference, one of his press assistants scurried to the stage, grabbing anything the president had touched so the items could be preserved for history.

The press seating chart on which Bush had scribbled notes, even if just to indicate the order in which he planned to call on reporters? That was now part of the presidential record.

And the note passed to Bush during a 2004 NATO meeting telling him sovereignty had formally been turned over to the Iraqis would've been preserved even if Bush hadn't scrawled on it, "Let freedom reign!"

Any document Bush looked at – including a dinner menu – was recorded as having been viewed by him and retained, typically by an assistant or secretary, according to a former aide.

Another former aide said Bush’s press shop explored, and then had to give up, creating Facebook and Twitter pages for Bush in 2008 because they couldn’t figure out how to archive social media without constantly taking screenshots.

The next administration, Barack Obama’s, was very conscientious about following the document control procedure, according to John Fitzpatrick, former senior director for Records Access and Information Security Management at Obama’s National Security Council.

When aides left the council, they created one set of boxes of archived materials and one of pencils, photos and other personal items. The box of personal items was scrutinized before the departing aide could take it out of the building, Fitzpatrick said.

Not a perfect system

But the records collections process is not perfect in any administration and it has bedeviled all of them.

Some Bush administration aides, including chief political strategist Karl Rove, came under fire in 2007 for using email accounts of the Republican National Committee for part of their work. Rove said he had been trying to avoid violating a law that prohibits government equipment from being used for campaign purposes and hadn’t realized that the emails sent through the national committee accounts were not automatically being preserved for the archives.

Opinion: Presidential records belong to the American people, not former presidents

During the Obama administration, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton used a private email address for exchanges with State Department staff. The State Department’s inspector general concluded she did not follow the department’s rules for handling records under the Federal Records Act, a law similar to the Presidential Records Act which applies to federal agency employees.

Controls extra tight for classified documents

Bill Leary, who was the senior director for records and access management at the National Security Council during Obama's first term, said the general rule during his tenure was to take the “broadest possible interpretation” of what would constitute a presidential record. If an aide, for example, read a newspaper article as part of her job, that article went into the archive.

Controls were especially tight at the National Security Council where the expectation was that nearly every document would need to be preserved. Each piece of paper with an official purpose that came into the council or was created by the council, was documented in a computer tracking system, according to Leary. That electronic record was ultimately transferred to the archives along with the paper documents.

A sheet attached to the box described everything in the box, which was put on a van or truck and transported to a secure area in the National Archives, according to Fitzpatrick.

Mick Mulvaney, who was Trump’s chief of staff from January 2019 until March 2020, said it’s hard to understand how classified documents ended up at Mar-a-Lago.

“These things are not sort of accidentally moved anywhere. These documents are marked,” he recently told CNN. “And there are supposed to be folks sort of tracking where they are.”

Threats toward FBI: Threats toward law enforcement were already on the rise. Then came Mar-a-Lago

Information incomplete: FBI seized top secret documents at Trump's Mar-a-Lago, but gave no clear hints on what they are

Trump denies wrongdoing

Trump has given various defenses for keeping the documents at Mar-a-Lago, including claiming without proof that he had declassified them. That argument has been rejected by former aides and experts.

The long, detailed and precise process for declassifying information includes consulting with any agency with a stake in the information and documenting what has been changed.

Declassified?: Trump claims Mar-a-Lago documents were 'declassified.' Why experts reject that argument.

The idea of the president, without any formal procedure, simply declaring top secret information declassified “leads to ridiculous situations in which we have no idea of knowing what it is that was covered by this, even assuming he had the power to do so,” said Glenn Gerstell, formerly the top lawyer at the National Security Agency who served in that nonpartisan position during the Obama and Trump administrations.

Whether or not the documents were declassified also isn’t a legal factor in the potential crimes the FBI cited in the search warrant used to retrieve the materials. Trump could still be charged with mishandling government documents under two of the statutes cited and could have violated the third – the Espionage Act – even if the documents were not classified, Gerstell said.

“The short answer is, declassification is irrelevant to the three statutes that are mentioned in the search warrant,” he said.

Trump's No. 2: Former VP Mike Pence says he didn’t leave office with classified material

What the FBI searched for

The warrant authorized investigators to retrieve any presidential records as well as "any evidence of the knowing alteration, destruction, or concealment of any government and/or Presidential Records, or of any documents with classification markings."

The search came months after the Archives, in January, retrieved 15 boxes of presidential records from Mar-a-Lago including more than 700 pages of classified material.

Documents released by the National Archives in response to Freedom of Information Act requests show concerns raised by Democratic members of Congress and others throughout Trump’s presidency about his administration’s compliance with the records act. The correspondence also shows the Archives had reached out to the White House counsel's office in 2018 following a Politico report that Trump would rip up documents which aides then had to piece back together for the records.

In January, the Archives stated the records they'd received from Trump included documents that had been torn up and taped back together "along with a number of torn-up records that had not been reconstructed by the White House."

Leonard, the former chief of the Information Security Oversight Office of the National Archives, said the White House office specifically devoted toward records access and management appears to have had “one hand tied behind their back” during the Trump administration, with aides “literally scurrying around, taping together pieces of paper that required retention and preservation.”

“It was a very chaotic process,” he said.

'We told you so'

As the Trump administration was winding down, attorneys from liberal good government groups and historians went before then-D.C. District Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson seeking an emergency injunction. Attorney Anne Weismann wanted to force the White House and its Department of Justice attorneys to sign promises that rules would be followed for departing White House employees. She worried they would be destroying and taking records with them wrongly.

“The Justice Department fought us tooth and nail and assured us, 'don’t worry, we have all these protocols and directives,'” Weismann said in an interview. “It’s galling now to look back. We’ve been saying ‘we told you so’ for weeks.”

Senate GOP leader: Mitch McConnell cautious on GOP's odds of taking Senate in midterms, rebukes threats to FBI

Social media: Lawmakers press Meta, TikTok, Truth Social over threats to FBI after Mar-a-Lago search

According to a transcript of the hearing, a DOJ attorney assured Jackson that “there shouldn’t be any doubt” that the White House “is extremely vigilant about managing departing employees records.”

Jackson took the government at their word in December 2020 and the case was dropped.

Now, that same civil DOJ office, and the same lead attorney, Elizabeth Shapiro, have sued former Trump adviser Peter Navarro for taking records with him when he left the White House.

“It’s the same issue in reverse,” Weismann said. “In my mind what was so troubling: we’re talking about our history, once it’s gone it’s gone.”

'Boggles my mind'

Leonard is still reeling from the fact that documents with the highest level of security classification were at Mar-a-Lago, which is not just Trump’s home but a private club.

“It just boggles my mind in terms of, how did we ever get to this point where, you know, we’re concerned about the busboy catering a wedding having access to nuclear secrets?” he said.

For history: Portraits of Trump, Melania in Smithsonian among latest spending for ex-president's Save America PAC

Sharon Squassoni, who specialized in nuclear arms control and security policy while working at the State Department and is now at George Washington University, said Trump’s actions reveal “a lack of respect for procedures and security and worse, it reveals a misguided notion of power.”

But, she added, more will have to be revealed about the documents Trump had in order to gauge the seriousness of the breach.

“What Trump did was alarming,” she said. “But we won’t know the extent of the impact until we find out a little more.”

Contributing: Bart Jansen and Erin Mansfield, USA TODAY

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Trump's Mar-a-Lago storage violated National Archive's records rules