Rude Daring: The Fashion Legacy of Thierry Mugler

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Several floors below "Thierry Mugler: Couturissme," the new exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum, a yellowing, staple-bound fashion zine is on display. The 1975 "Glamour" issue of File by the Canadian collective General Idea, is propped open to an essay on a subject that deeply concerned both the designer and the group: being gorgeous.

“Gorgeousness,” the text reads, “is a twenty-four hour pre/occupation. Its exquisite self-image stretches beyond Idealism or mere vanity. It has as much to do with self-knowledge as self-love.”

The levels of camp within this statement are off the charts; it is an ultra-serious, hyper-fabulous comment on the importance of attractive surfaces. But rooted in the piece is an idealism and emotional truth that the late Manfred Thierry Mugler pursued throughout his 50-year career.

Like General Idea, the French couturier’s understanding of “Gorgeousness” was of a perfected, even impossible dream to become one’s best self. It was an ideal that he sought to embody: both creatively—in the production of clothes that transformed women into superheroes, dominatrixes, and alien queens—and literally, as he body-built himself into a living statue of Zeus. When it was announced earlier this year that Mugler died, the news came as a shock. He had lived so much of his life as an outsized, legendary creature that it was as if Bigfoot or Cher or the Great God Pan had finally kicked the bucket.

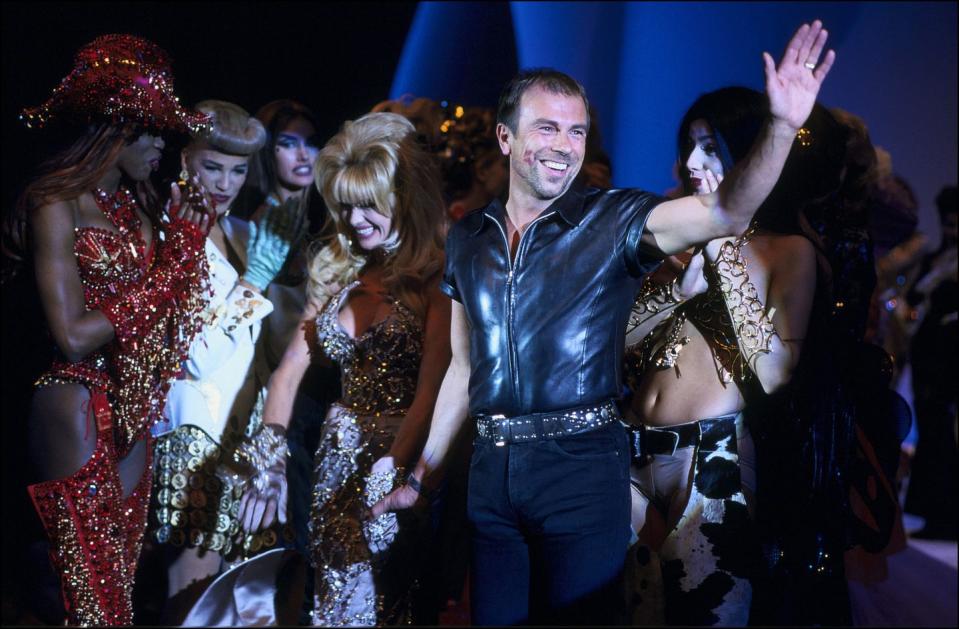

In the immediate aftermath, social media was flooded with tributes to the designer. His most iconic looks were trotted out: Kim Kardashian dripping in nude-illusion Swarovski crystals at the 2019 Met Gala, Cardi B dressed as a ballerina “Venus in a Half-Shell” at the Grammys, Lady Gaga and Beyoncé on tour as postmodern dance machines. There were highlight reels of signature shows: Tracee Ellis Ross’s runway debut alongside her mother, Diana; the unhinged glamour of Lypsinka’s 1992 performance; the successive waves of supermodels, club kids, and old Hollywood vamps storming the stage for his 20th anniversary.

In addition to these remembrances, there were Instagram posts that conjured the sense memory of anyone who had fallen in love with (or been suffocated by) the scent of Angel in the 1990s, and the recollections of those who knew the designer first-hand or, simply, emboldened by his clothes.

"Thierry Mugler: Couturissme" doesn’t fully unpack the totality of his maximalist, sui generis legacy, but it does offers up one of the most concentrated blasts of his artistry. The exhibition, which originated in Montreal and is open to the public at the Brooklyn Museum through May, is an orgy of archival fashion organized not chronologically—curator Thierry-Maxime Loriot assured Mugler the show wouldn't feel backwards-looking—but thematically along the lines of the designer's major interests and obsessions, like 1960s sci-fi robotics, mutant chimera biology, feathered showgirl flamboyance. It is staged with an exuberant theatricality in the spirit of Mugler's most over-the-top work.

Where good designers are known for creating new kinds of clothes, legendary designers are famous for creating new kinds of women. Mugler’s most enduring contribution was bringing about the dawn of the “Glamazon.” The Glamazon—part glamour-puss, part Amazon—was defined less by style than by force of personality, capable of adopting any look or costume so long as she is in the dominant position.

The major hallmarks of Mugler’s design—padded shoulders, architectural silhouettes, form-fitted body suits—telegraph a brazen confidence that challenges the wearer to live up to it, a self-belief that one immediately associates with the women who played his muses and models: Grace Jones, Jerry Hall, Iman. A quote by the designer inscribed at the entrance of the show sums up his lifelong project: “In my work I‘ve always tried to make people look stronger than they really are.”

In Brooklyn, a gallery dedicated to Mugler’s design for the 1992 music video of George Michael’s “Too Funky” is emblematic of the show at its flamboyant best. The garments themselves are incredibly striking and have occupied my imagination for years. A scarlet bugle-beaded cowboy outfit accessorized with a hilariously sequined hamburger purse is a marvel to behold in person, ditto the metallic Harley Davidson-inspired corset with rear-view mirror appliqués and a quilted leather, heart-shaped “loveseat.” Elsewhere, a series of S&M-inspired looks–a dress suspended by a pair of nipple rings and an ass-less “derrière décolletage”–is still kinky, seductive, and hilarious for its rude daring.

From there, the exhibit snakes into highlights from his work with celebrities and costumes for musical revues, as strict leather gives way to neon crinolines, wrought-iron panniers, and peacocking trains and headdresses fit for pop stars and Vegas showgirls. In looks like these, his rubber tire dresses and cyborg body suits, Mugler pioneered a form of pop art couture where people and things were wildly interchangeable and distinctions between high and low were thrown joyfully out the window.

This was post-modernism at its most fun and immediate, when a designer was afforded near-infinite permission to remix, reference, and appropriate, channeling a chaotic chemistry where drag queens and divas, porn stars and princesses could all meet on the same runway. "Couturissme" demonstrates over and over how good Mugler made on this promise.

Mugler's fashion wasn’t tinged with the masochism or contempt for weakness that lurked behind the work of his contemporary, the late Claude Montana. And charges that Mugler fetishized impossible beauty because he was a 'fascist' have always rung hollow. Instead, Mugler had a wider and more poetic definition of what a strong woman could be and seemed to be the rare fashion type who didn’t set out to impose his own impossible standards but to enhance the brilliance of others.

Michael’s “Too Funky" was filmed at the tail-end of an increasingly bitter relationship with Sony Music, and the singer's decision to put supermodels front and center was both a refusal to play the part of pop star and a metaphor for the fierce defiance he wished he embodied. For much of "Couturissme," I wondered about Mugler’s own motivations, what he himself wanted to live out through his clothes. While the exhibit is a stunning undertaking, it sometimes upstages the man behind the glamour, glossing over the contradiction between his humility and his grandiose striving for perfection. Mugler himself seemed all too aware of the potential of the dress, his dresses in particular, to wear the woman rather than the other way around.

Perhaps that's why the purest expression of his dreams of enormity wasn’t his fashion but his photography. Having collaborated with the likes of Helmut Newton, Lillian Bassman, and Guy Bourdin to bring his work to life, Mugler eventually took up the camera himself. It is in shooting his favorite muses against icebergs in Greenland and sand dunes in the Sahara that he found a new scale for his work that both exceeded and complemented the body, always exalting the individual against vast, fantastical backdrops.

You Might Also Like