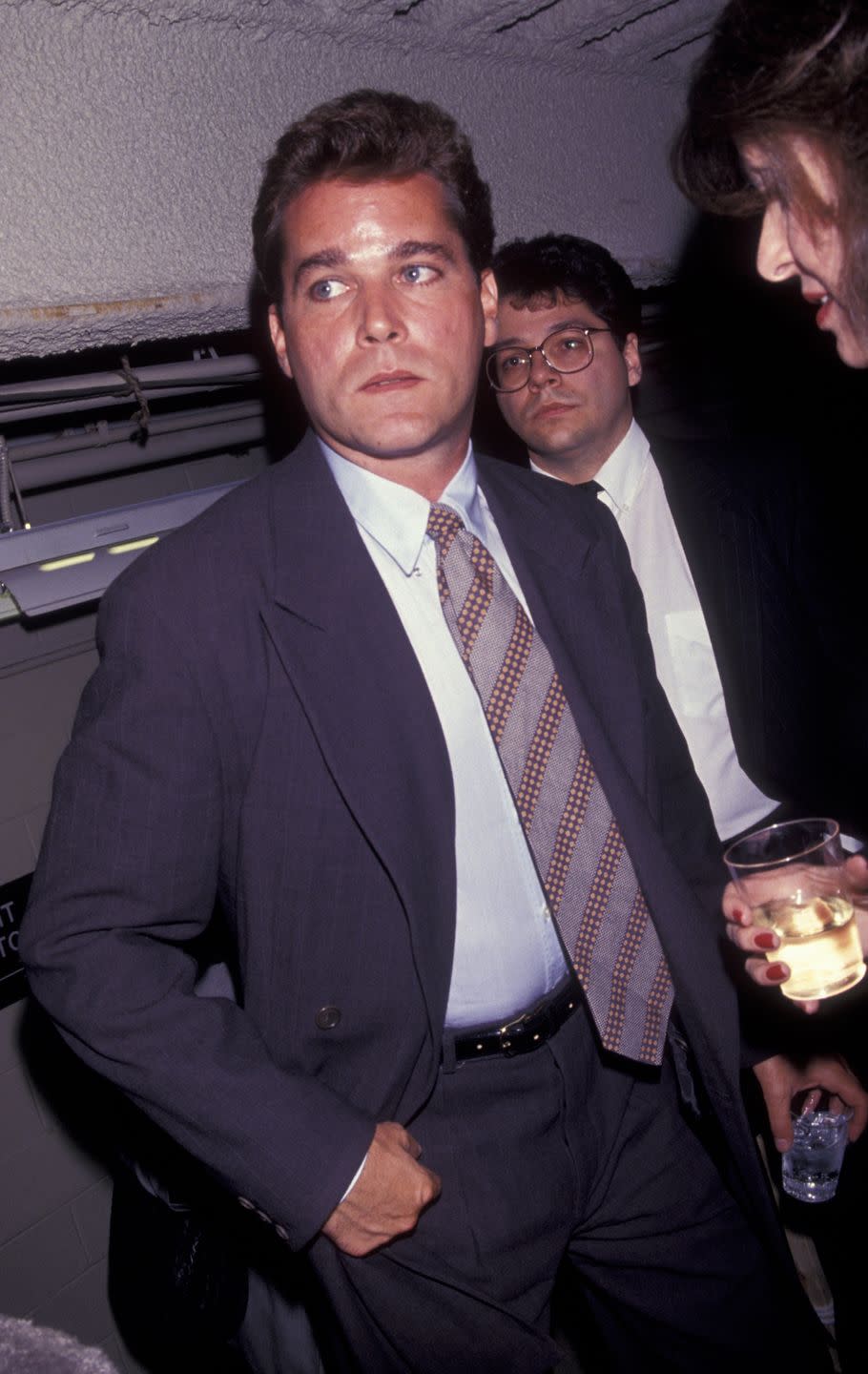

The Rough-Hewn Elegance of Ray Liotta

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The fall of 1986 saw the release of arguably the two best American movies of that decade: David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild. More people saw Blue Velvet. But it’s likely that Something Wild caused more upset to its audiences—and all of that is due to Ray Liotta, who died this week at 67.

Lynch’s movie, with its opening shots of gleaming white-picket fences and roses so red under skies so blue, makes you dread what’s coming from the beginning; nothing that looks this good could last. Demme’s movie, on the other hand, seduces you into what feels like a sexy lark, another of his celebrations of roadside American eccentricity that, in Handle With Care and Melvin and Howard, marked him as the hip heir to Preston Sturges. Something Wild is a kind of spiritual remake of Sturges’ The Lady Eve, both of them comedies about a sensible young man whose life is set askew by an unconventional young woman, a young man who has to see the woman in front of him for who she is and not the fantasy he has of her. The man is Jeff Daniels’ Charlie, a deeply conventional stockbroker, and the woman is Melanie Griffith’s Lulu, a downtown shoplifter and sensual free spirit in a Louise Brooks bob. As the pair road trip south, with an eventual destination of Lulu’s high school reunion, Charlie comes to realize that she represents the life of freedom and pleasure his own suburban existence has leeched away. He knows whatever future there is for him has to include her. And then Liotta’s Ray Sinclair arrives—and Charlie is going to have to fight for Lulu, for that future he envisions, for his own life.

Ray Sinclair is Lulu’s ex-con ex-husband who shows up to win back the woman who served him divorce papers while he was in the joint—and he’s none too happy to find her on the arm of some cornfed hunk who a few years back was probably captain of his high school baseball team. Our first glimpse of Ray puts a sliver of ice in the movie’s heart. Charlie and Lulu are slow dancing, kissing, lost in the moment. It’s the reverie of romantic bliss no one who finds themself in it wants to end. But something is off. The band has dug into some ominous riff, the lights have gone midnight blue and Ray, part of another couple dancing by, uncoils himself from his partner and greets Lulu with: “Hi, baby. Surprise.” With no explanation, Lulu tells Charlies she wants to go. And Ray just looks after her, his eyes ice blue, a faint smile on his face. It’s a look that tells us Lulu is never getting far away from him, a look that tells us he’s in charge.

Liotta’s method is more feline than feral. With his greaser’s wardrobe—rolled-sleeve t-shirt, jeans, nose-picker-point cowboy boots—black hair swept back from his acne-scarred face, thin-lipped smile drawn tight over a cruel jaw, Ray looks very much the classic badass. When he greets a classmate, a small, quiet woman with a demure face (Su Tissue of the seminal punk band Suburban Lawns), you see immediately how terrified she was of him in high school—and still is. Ray is mostly insinuation, which makes his moments of actual violence so frightening. You don't warm to his character like Mickey Rourke’s arsonist in Body Heat. You feel as if he's going to set the screen on fire at any moment. Liotta doesn’t grandstand, he doesn’t throw the movie out of whack. But in context, his stated aim—winning back Lulu—is about as believable as thinking Iago wants payback for Cassio getting his lieutenancy. Which is to say it’s not believable at all. Ray’s aim is to take a flamethrower to everything around him for the sheer pleasure of watching it burn. He can even be kind of fun. Cruising the streets with Lulu and Charlie he wants to play the host, out for a night of beers and laughs. When Charlie stands up to him, Ray, amused, responds with a Tony the Tiger grrrr. But when it looks like Charlie is going to win, Ray’s face turns to what stone would look like if stone could seethe.

Which is why, even after keeping our guts tied up in knots for every moment he’s on screen, Ray’s death is so upsetting. He’s invaded Charlie’s suburban home, beaten up Charlie and Lulu and is preparing for worse when he inadvertently runs into the switchblade Charlie is holding out. Demme shoots the moment so that we see Ray’s face—the surprise and realization—right as the knife goes in. And the line that follows—“Shit, Charlie”—accompanied by a little laugh, registers nothing so much as bewilderment. It’s as if Ray is saying, “We were having fun weren’t we? Whadja wanna go and do that for?” Demme gives Ray a gunfighter’s finish, walking off to his fate, the heels of his cowboy boots leaving behind his own blood with every step.

It’s a great performance—unnerving, charismatic, impossible to resolve your feelings about. But it may be Liotta’s performance in Martin Scorsese’s 1990 Goodfellas that defined him for most moviegoers. As the aspiring wiseguy Henry Hill, Liotta is the audience’s cock-of-the-walk stand-in. For those who’ve succumbed to Goodfellas over the last thirty-two years, Henry may be as much of a fantasy figure as James Bond. Near the end, as witness protection is about to force him to give up his good life, he talks about all he’ll miss—the jewelry and clothes and drugs and never having to stand in line like every other schmuck. It’s a larcenous version of the working-class utopia Norman Mailer outlined in Miami and the Siege of Chicago: “sex in their pockets, muscles on their back, hot eats around the corner, neighborhoods which dripped with the sauce of local legend . . . carnal as blood, greedy, direct, too impatient for hypocrisy, in love with honest plunder.” Goodfellas isn’t just Henry’s fantasy, it’s Scorsese’s, a compendium of what the director loves about wiseguy lore and style, presented in sweeping, virtuosic camera movements as showy as a sharkskin suit and a mirror shine on your shoes.

At the center of the vision is Liotta’s Henry, the hood as matinee idol, with his pompadour and his slick suits and collars so long and pointed they hide his ties as if they were some sacred mystery. Henry has moments of violence, as when he pistol whips the neighbor who gets fresh with his girlfriend, played by Lorraine Bracco. And Liotta sweats off any glamour in his final scenes as a jittery, paranoid coke freak. But the beauty of Liotta’s performance is how its smoothness compliments the smoothness of Scorsese’s surfaces, his beaming face as he’s taken up by older made guys, the fuss made over him and his date when he cuts the line at the Copa and makes his way through the kitchen to be brought to a table for two right in front. Even the slight nervousness you can see in Liotta’s eyes as Henry checks his cuffs or makes sure he’s holding his cigarette at the right angle is that of a man wanting to make sure he’s measuring up to the dream image in his head.

It would be nice to say the movies did right by Ray Liotta but for too much of his career he was used unimaginatively, cast when somebody wanted a recognizable tough guy, and used in roles that didn’t afford him much color. It’s bittersweet to speculate what might have happened had he worked when movies knew how to provide roles for the likes of Lee Marvin or Ralph Meeker or Richard Conte. In the fall of 2006, TV offered up something better when Liotta, heading up an astonishing cast, did a series called Smith, about a group of thieves trying to keep their criminal lives separate from their personal lives. The show was off-kilter and smart and not interested in ingratiating itself with anyone. CBS chickened out and pulled the plug after three episodes.

If I could pick one performance of Liotta’s that I would love to see get the recognition it deserves, it would be in Paul Schrader’s 1999 Forever Mine. Sold off to cable when its financing company went under and almost completely unseen since, it’s one of the best movies of the ‘90s. It’s also the damnedest thing. Imagine a Douglas Sirk melodrama that uses The Count of Monte Cristo as the model for a study of political corruption from Nixon to Reagan.

Liotta plays an aspiring politician who thinks he’s does away with the cabana boy (Joseph Fiennes) who falls in love with his wife (Gretchen Mol) only to have that boy reemerge years later as the political fixer Liotta needs to get the Justice Department off his back. This is a movie that breathes the air of movie rapture. It’s the type of picture in which Mol makes her entrance rising from the ocean like Botticelli’s Venus, where Fiennes, in answer to a question, recites the lyrics of “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?” And it’s a movie in which Liotta stands in opposition to all that, almost in opposition to the charisma he had shown his whole career. As a pol whose only interest is lining his own pockets, Liotta makes himself ferrety and small. As the movie goes on, with his hair greased back in waves and his face becoming jowly, it’s almost as if he’s been body snatched by Nixon. There’s danger in the performance, but not the danger that characterized Liotta’s early work. It’s the danger of a man who wields power by pushing buttons and giving orders. He’s the movie’s lurking evil, but the bland kind of corporate evil who has leeched his way into our lives and the lives of the nation. And when you consider such a role played by someone who had shown such dynamism, such volatility, who found his own kind of rough-hewn elegance, the purr ready to turn into a snarl, you have a sense of how little vanity there was in Ray Liotta. And how much more we’ve been robbed of discovering.

You Might Also Like