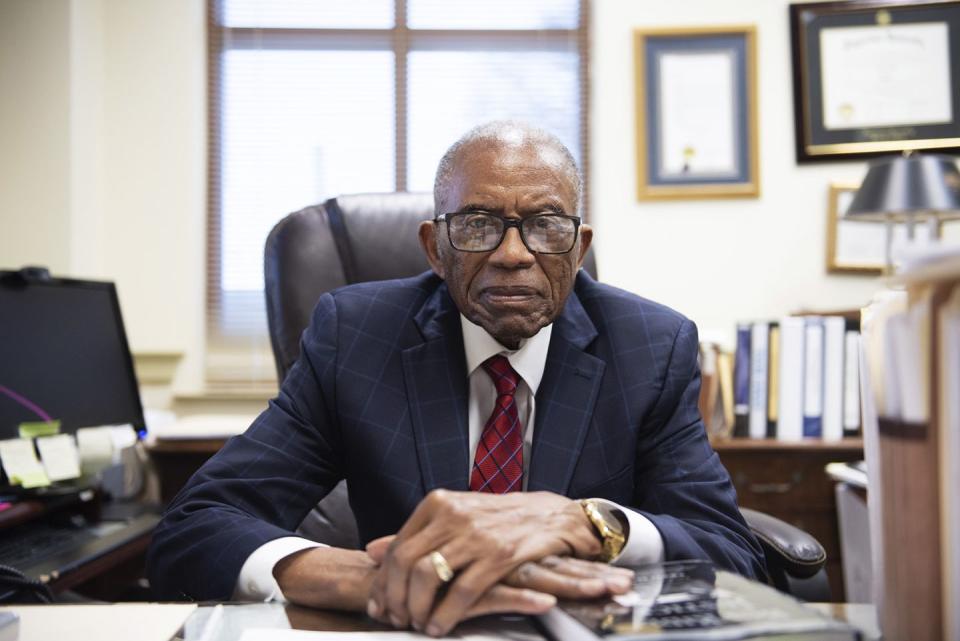

Rosa Parks's Lawyer Fred Gray Has Spent His Life Battling Segregation

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

As told to Hali Cameron/

Photograph by Andi Rice

I’m the youngest of five children. My father died when I was two. My mother had no formal education, except to about the fifth or sixth grade. But she told the five of us that we could be anything we wanted to be if we did three things. One, bring Christ first in your life. Two, stay in school and get a good education. And three, stay out of trouble. I have tried to do all three of those things. And they have helped me to do all the other things I have done.

When I finished my high school work, at that time, as a young Black man in Montgomery, basically the only two real professions you could look forward to, one was preaching and one was to be a teacher. And if you did either one, you did it on a segregated basis, because everything was segregated. So I decided I would be both. And I enrolled at what was then Alabama State College for Negroes, now Alabama State University. It is on the east side of Montgomery, and I lived on the west side of Montgomery. So I had to use the public transportation system every day.

As I used that system, I realized that people in Montgomery, African Americans in Montgomery, had a problem. They had a problem with mistreatment on the buses, and one man had even been killed as a result of an altercation on the bus. I didn’t know nothing about lawyers, but they were telling me that lawyers helped people solve problems. And I thought that Black people in Montgomery had some problems. And not only that, everything was completely segregated. So I made a commitment, a personal commitment, a private commitment. And that was that I was going to go to law school, finish law school, take the bar exam, pass the bar exam, become a lawyer in Alabama, and destroy everything segregated at the time. Now, for a young teenager to think that way, you may say I was thinking a little bit out of the box.

On the seventh of September 1954, I became licensed to practice law in the state of Alabama. I then was ready to begin my law practice and begin destroying everything segregated I could find.

Dr. King came to Montgomery just about the same time I started practicing law. He was installed as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in October of 1954. But nobody knew Martin Luther King. He didn’t come to Montgomery for the purpose of starting a civil rights movement. I doubt whether he knew anything about civil rights. The church that he became pastor of, Dexter Avenue, was a small African American Baptist church that consisted of basically educated persons who were employed by some governmental agency or another, and all of those governmental agencies enforced segregation. So that church would have been the last church whose members would have ever filed a lawsuit to desegregate anything in Montgomery. And the pastor that they had before him, Vernon Johns, they got rid of him because he was too liberal. So nobody knew anything about Dr. King when he came to Montgomery. And, but for what Mrs. Rosa Parks did, and what Claudette Colvin did—if they had not done that, probably nobody would ever have known who Martin Luther King was.

I had met Mrs. Parks when I was in college at Alabama State. She was then and for quite a while secretary of the Montgomery branch of the NAACP. She was also the director of the youth program, and of course the young people she was dealing with when I was in college were just a little bit younger than my age. So I used to visit some of her meetings. After I came back to start practicing law, I renewed my relationship with Mrs. Parks. In our meetings we had talked about the way a person should conduct themselves if the opportunity presented itself and they were asked to get up and give their seat on a bus. And Mrs. Parks was the right type of person. We didn’t want somebody who would be a hothead, or who they could accuse of being disorderly, but someone who would let them know they were not going to move. If they were told that they were under arrest, they would go ahead and be arrested. And we would try to be sure that somebody was there to take care of them.

We also knew that it was going to take a lawsuit in federal court in order to have the laws declared unconstitutional. And we knew that would take time. So we felt we couldn’t tell the people to stay off of the buses until they could go back on a non-segregated basis. But the plan was, let’s tell them to stay off of the bus one day, on Monday, the day of Mrs. Parks’s trial. And then we’ll decide where we go from there.

Somebody had to be the spokesman for the group, to tell the people and tell the press what we were doing and why we were doing it. It needed to be a person who could speak, and someone said to me, “Well, I’ll tell you, Fred, the person who can do that the best of anybody I know is my pastor, and that’s Martin Luther King.” He hadn’t been in town long, and hadn’t been involved in any civil rights activity. But he could move people. I said, “If he can do that, that’s the kind of person that we need.”

It didn’t take long to try Mrs. Parks’s case because I knew they were going to find her guilty, and I was gonna have to appeal it. So I simply raised the constitutional issues. We had a trial that took less than an hour. She was convicted; we posted the appeal. And they had a mass meeting that night at the Holt Street Baptist Church. And when Dr. King spoke, everybody knew. And that is the beginning of how the bus boycott started. And the people stayed off the buses for 382 days.

As a result of people seeing what had happened in Montgomery, the thought then was, If you can solve a problem with staying off the buses, then Black people can solve their problems elsewhere. So you had the students up at A&T that started the sit-in demonstrations at the lunch counter. You had all of these people getting involved in what developed into the civil rights movement as a result of seeing what the 50,000 African Americans had done in Montgomery.

I have now been practicing law for some 66 years, and it all started because when I was a student at Alabama State, I made a decision that I was going to destroy everything segregated I could find. Doing away with segregation on buses was just the beginning of my career. I’ve filed lawsuits that have ended segregation in the University of Alabama. I represented Alabama State in a case that ended up desegregating all of the other institutions of higher learning. Our responsibility, and the responsibility that the NAACP and other groups were working on since slavery, was filing lawsuits one at a time, one area at a time, and getting the court to declare it unconstitutional. We have for the most part knocked out those laws. However, the most discouraging thing for me and my practice in Alabama was that I was naive enough to believe that when the white power structure in this state saw that African Americans could perform as well as they, or better in some instances, that they would be willing to accept it. But while we have knocked the laws out, the attitudes of some persons have not changed. But we have made a tremendous amount of progress.

The best advice I can give to young people—and old ones too, for that matter—is, look in your communities. See the problems that exist? Do as we did in Montgomery: Let’s talk about those problems. Don’t just run out on your own and try to solve it all, but work with others. And you may find that there are other people in the community who believe that what you think is a problem is also a problem to them. And you may be able to get together. And by talking and working and formulating, you just might start a movement.

Use your own good common sense and help to finish the job of destroying racism and destroying inequality. Things certainly have changed, but what has not changed is racism and inequality. And that was my object, to get rid of those two things. But it’s gonna be up to you to do it.

About the Journalist and Photographer

Turn Inspiration to Action

Consider donating to the National Association of Black Journalists. You can direct your dollars to scholarships and fellowships that support the educational and professional development of aspiring young journalists.

Support The National Caucus & Center on Black Aging. Dedicated to improving the quality of life of older African-Americans, NCCBA's educational programs arm them with the tools they need to advocate for themselves.

Credits: Andi Rice: Amanda Rice

This story was created as part of Lift Every Voice, in partnership with Lexus. Lift Every Voice records the wisdom and life experiences of the oldest generation of Black Americans by connecting them with a new generation of Black journalists. The oral history series is running across Hearst magazine, newspaper, and television websites around Juneteenth 2021. Go to oprahdaily.com/lifteveryvoice for the complete portfolio.

You Might Also Like