Classic rock is dying before our eyes – and it’s heartbreaking

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The first truly on-brand rock’n’roll death took place on Christmas Day, 1954, when Johnny Ace shot himself in the head with a .32 calibre revolver loaded with just one bullet. Although eyewitnesses denied the 25-year-old was playing Russian Roulette in the communal dressing room between sets at a Christmas Dance in Houston, no one disputed that the singer was under the influence of both alcohol and stress.

It was understood by those who knew him that Ace liked to play with guns as a means of letting off steam. On his last night on earth, he produced a pistol bearing five empty chambers that he duly waved in the direction of other members of the concert troupe. After being admonished for these foolhardy actions, it was explained that the danger was merely illusory; Johnny Ace knew in which chamber the bullet was nestled. Only he didn’t. Pointing the pistol at his own head, he pulled the trigger and ended his life with immediate effect.

The tragedy ricocheted across America. Described by Paul Simon as “the first violent act that I remember”, the event served as the catalyst for the track The Late Great Johnny Ace, in which a teenage boy sends for a photograph that “came all the way from Texas” of a recently deceased singer “with a sad and simple face”. A decade later, bullets have stolen the life of an American president. The song’s end sees its narrator “walking through the Christmastide when a stranger came up and asked me if I’d heard John Lennon had died”. Murdered, actually. Assassinated. Yet another extraordinary musical death.

This is how rock stars used to go: suddenly, unexpectedly and far too young. Many as young as 27 – Brian Jones, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain and, more recently, Amy Winehouse – which led to the term “the 27 club”, a club nobody wanted to join.

And yet the so-called 27 Club turned out to be very much a myth, according to a 2015 study by the academic Dianna Theodora Kenny. Far more musicians died at 28, she found; though by far the most common age to expire was 56. In 2016, Bayes Business School found that cancer, drug overdose and excessive alcohol consumption were among the main causes of rock star deaths, and these rock gods were twice as likely to die between the ages of 55-69 as the general population.

But it turns out that not even rock’n’roll can kill everyone. Turns out, in fact, that we’re at last reaching the point at which the people who produced some of the greatest art of the 20th Century are clocking out from old age. In the last few months alone we've lost David Crosby (81), Jeff Beck (78), Christine McVie (78), Burt Bacharach (94), Tom Verlaine (73), Jerry Lee Lewis (87) and Ronnie Spector (78). Average age? A ripe old 81.

Many vintage musicians still knocking about have actually found their advanced years to be quite a bankable commodity. I don’t imagine that Bruce Springsteen would be charging up to four figures for a ticket to his current tour were it not for the very real possibility that it might be his last. Similarly, audiences who ponied up the highest price on the market for last year’s Paul McCartney Glastonbury headline gig did so in the knowledge that opportunities to say “I was there” were fast running out.

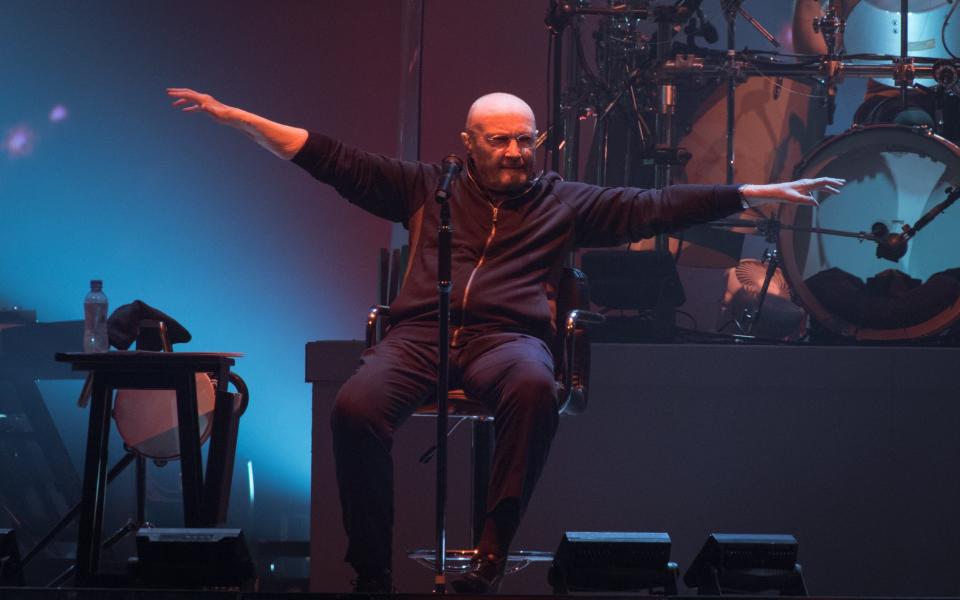

This summer, Billy Joel will be 74 when he tops the bill at London's Hyde Park. And, after performing over two nights at the same space, as well as an evening at Anfield, last year, 2023 will likely see a brand new album from the Rolling Stones. However, I can't have been the only person who winced at the sight of Phil Collins onstage last spring with Genesis, trooping away in apparent frail health from a sedentary position throughout the show.

Others, however, would rather not rock until they drop. Elton John is hanging up his microphone at the end of this year, when he finishes his Farewell tour. In January, The Who announced this first tour in six years, but this week revealed retirement was already playing on their minds – because, said Pete Townsend to The Sun, “We're both old”. Perhaps they won't have a choice. As Roger Daltrey this year told Record Collector magazine, “I've always said that you don't give this business up, it gives you up.”

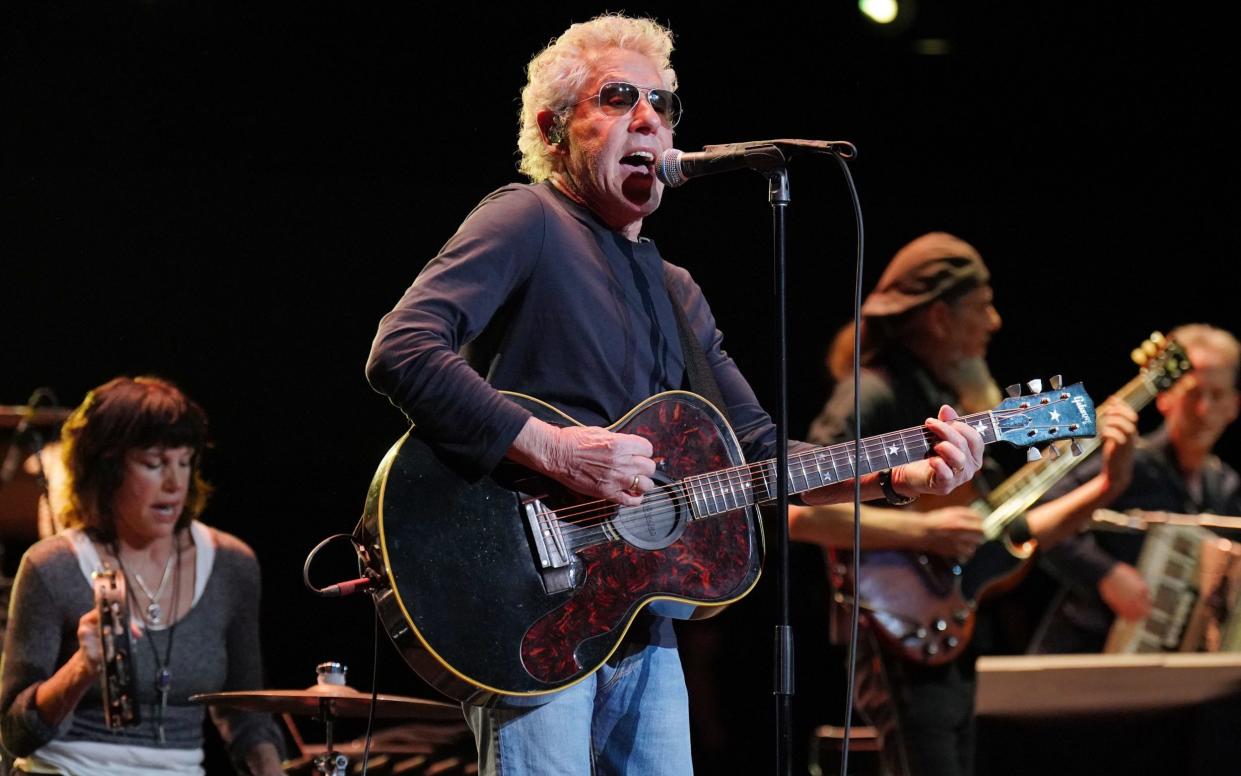

In 2018, then 76-year-old Paul Simon wrote in a statement announcing his retirement that he'd “often wondered what it would feel like to reach the point where I’d consider bringing my performing career to a natural end. Now I know: it feels a little unsettling, a touch exhilarating, and something of a relief.”

The public decline and deaths of people who once appeared immortal is a deeply sobering reminder of a universal tolling of the bell. We’re seeing a trickle that is becoming a flood. In 2015 and ’16, the death of Lemmy and David Bowie within three weeks of each other seemed like natural acts of terrible cruelty. But now, just seven years later, it seems you can’t turn on the radio without hearing the news that yet another musical great has drifted into the past tense.

Next year, the 70th anniversary of the release of Rock Around The Clock means that the first generation of rock and rollers who still walk among us are likely in their 90s. The boomers of the Sixties are a mere decade younger. Even the punks have taken possession of their bus passes. Likely we will go out like Terry Hall, or Andy Fletcher from Depeche Mode. Never before has rock’n’roll been relatable in this way.

Which is why the communal grief that swelled in response to the deaths of Jeff Beck and David Crosby was so different from that which might have greeted an unfortunate new member of the 27 Club. In it, one could detect notes of genuine empathy, and perhaps, even, quiet panic. Because people who saw The Yardbirds at the Marquee club, or The Byrds at the Whisky A Go Go, are unlikely to need reminding that time and tide waits for no man.

Of course, rock stars do still check out early. Despite numerous “conversations” about mental health and cleaner living, the world they inhabit remains an unsafe place of work. In recent years, Chester Bennington, Chris Cornell and Keith Flint – the singers with Linkin Park, Soundgarden and The Prodigy respectively – have each died by suicide. Following the death last year of Taylor Hawkins, in drug-related circumstances, last year’s concerts in the drummer’s honour, hosted by his band the Foo Fighters at Wembley Stadium and the Forum in Los Angeles, were likely the most star-strewn events since the Live Earth happenings 15 years earlier.

But whether tragically or timely, our favourite artists will likely be laid to rest before our eyes. Just last month, in fact, I went to see my own Desert Island Artist of years longstanding. Queuing for the door of the Gramercy Theatre, in Midtown Manhattan, a marquee bearing the words “Citi Presents Elvis Costello – 10 Nights Sold Out” promised an instalment in the residency of a world-class songwriter now barely a year away from his eighth decade.

Over the course of two working weeks, in New York City, the 68-year old treated his audiences to set-lists comprising more than 200 different songs that to my ear are among the finest in the history of recorded music. When their author retires, and then worse, at least his life's work will be there to keep me company.

As the encore approached, Elvis Costello played an exquisitely clever song called God’s Comic. “Now I’m dead,” he sang. “Now I’m dead, now I’m dead, now I’m dead…”