Resurrecting A Lost Palace of Haiti

I visited Dominican artist Firelei Báez’s large-scale installation of King Henry Christophe of Haiti’s famous 19th-century palace during the final weekend of its exhibition at Boston’s ICA Watershed. Báez’s re-creation of the breathtaking castle called Sans-Souci (meaning “without worry”), which was partially destroyed by an earthquake in 1842, reflects as much the deep history of the Caribbean island Haiti shares with the Dominican Republic as it does contemporary political problems and environmental concerns in the region.

This year, Haiti experienced all the phenomena called forth by the installation: anti-government demonstrations, the death of their head of state, a massive earthquake in the southern city of Les Cayes, followed by a tropical storm that brought devastating floods. This was all compounded when in September, border agents in Del Rio, Texas, began expelling Haitian migrants seeking U.S. asylum. They had been sheltering under a bridge near the Rio Grande River between Mexico and the United States.

As a Haitian American, I couldn’t help but to feel all too acutely the painful relevance of Báez’s artwork as it intersects with the ongoing crises facing Haitians in Haiti and Haitian migrants across the Americas. But as a historian of the Caribbean, who is currently writing a book about the Kingdom of Haiti, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of gratitude that this enormously important but relatively unknown history appeared in a city like Boston, which after Miami and New York, contains the third-largest Haitian-American community in the United States.

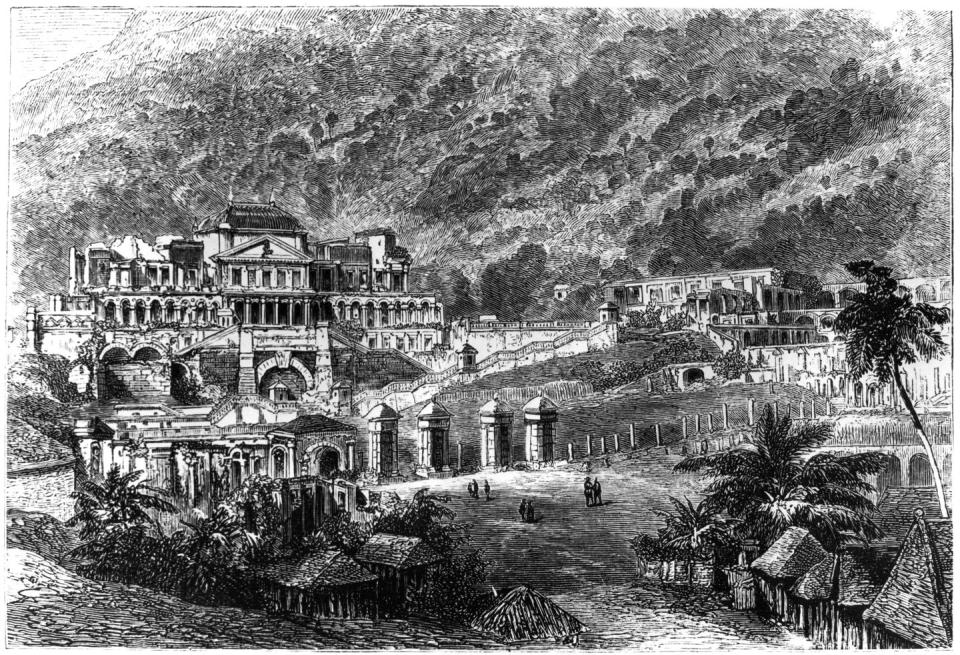

Haiti’s first, last, and only king, Henry Christophe, fought in the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), which ended slavery and colonialism on the French-claimed island of Saint-Domingue (today, Haiti). When Christophe became king of the northern part of the country in 1811, he sought to create monuments to Haiti’s War of Independence that would “attest for centuries to come to the memory of this glorious event!” Completed in 1813, his castle was also a visible testament both of Haiti’s wealth and prosperity after slavery, and the Haitian peoples’ origins in Africa. The kingdom’s most prolific writer, Baron de Vastey, said that the palace was proof Haitians had not lost “the architectural taste and genius of our ancestors who covered Ethiopia, Egypt, Carthage, and Old Spain, with their superb monuments.”

The palace was also admired by Haiti’s many foreign visitors. British traveler James Franklin judged that Sans-Souci was “little, if at all inferior to some of the most admired edifices of Europe.” New England travel writer and physician Jonathan Brown visited Sans-Souci in the 1830s, long after the king’s suicide in 1820, when the palace had been completely pillaged and had fallen into utter desuetude. Even though Sans-Souci resembled only the shadow of its formerly opulent state, Brown could not help but be wonderstruck by the castle he called “a sort of Louvre.”

On May 7, 1842, the city of Cap-Haïtien suffered a magnitude 8.1 earthquake whose tremors were felt as far away as Arkansas. The quake crumbled the former kingdom’s capital and unleashed a deadly tsunami. Nearly 10,000 people died and virtually every structure suffered catastrophic damage. Haitian novelist and historian Demesvar Delorme was only 11 years old at the time, but he recalled that around 5:30 p.m. “a deafening thud, a distant, mournful rumbling, as if emerging from a deep abyss was heard.”

He continued, “The bell tower of the Cathedral began to sway in the air, the bell’s chimes were ringing in full blast, sinisterly, without rhythm; a horrible death knell. Then the bell tower crumbled, the upper part first. Then the church came down altogether, and all the surrounding houses, and all the houses for as far as I could see; and all the streets came down afterward, and finally the whole city.”

The former palace of northern Haiti’s king, located about 10 miles from the epicenter, was not spared. Amid the untold human suffering, Delorme could not help but to grieve the loss of the enormous edifice, whose proportions he described as “extending on each of its four sides like three quarters of the facade of the Tuileries.” Damaged beyond repair, today the palace’s remains have been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Travelers who come to see Sans-Souci from around the world are still awed by the remnants of its combined Baroque and Neoclassical style. After visiting the ruins, PBS’s Henry Louis Gates Jr. remarked, “Though a devastating earthquake destroyed much of it, it remains a grand, imposing, gorgeous structure, something right out of a fairytale.” Christophe’s equally imposing Citadel, constructed to protect Haiti from foreign invasion, was finished around the same time as the palace and has been called the eighth wonder of the world. But it is Sans-Souci that holds the magic and mystery of a time now largely forgotten.

Hurricanes and tropical storms reconfigure the geography, landscape, and architecture of the Caribbean archipelago—which stretches more than 4,000 kilometers and contains upward of 7,000 individual islands—on a yearly basis. The region’s susceptibility to earthquakes makes ruins as much a part of the landscape as palm trees. The focal point of Báez’s artistic reimagining of the castle is Sans-Souci’s still-standing hall of mirrors. The blue tarps that shroud the structure from floor to ceiling—with handmade cutouts that look like stars or small fish glowing under sparkling lights—were inspired by those used after storms in the Caribbean as temporary roofs or makeshift shelters. The indigo markings of lions and panthers painted on the stone columns—symbols found in 19th-century Haitian nobility—reflect West African print dye techniques.

More than 70 feet in length and 20 feet in height, Báez’s dramatic re-creation of the castle’s ruins earns its majestic title, To breathe full and free: a declaration, a re-visioning, a correction (19°36’16.9”N 72°13’07.0”W, 42° 21’48.762” N 71°1’59.628” W). Located in Milot, Haiti, Sans-Souci does not share this latitude and longitude, which is that of the Watershed. The United States and Haiti do share a revolutionary past, however. These entwined histories are evoked in the Watershed’s entranceway by Báez’s enormous mural of the Boston Harbor—where the American colonists once dumped 342 chests of tea in protest—featuring a Ciguapa, a mythological creature in Dominican folklore.

The interlocking ecological and political problems facing today’s Haiti were further magnified by the soundscape playing on speakers in the reconstituted palace’s arches—an overlay of first-person testimony from Haitian and Dominican migrants to the United States, with sounds of the ocean recorded from the Boston marina and the Caribbean Sea. In the four or five different constantly playing tracks, visitors heard voices in Spanish, English, and Haitian Creole telling their stories of migration and talking about the meaning of the word home.

Báez has said that as a child growing up in the Dominican Republic, she was told that the Caribbean has no history and, therefore, no storied monuments to speak of. In his poem “The Sea Is History,” St. Lucian poet and playwright Derek Walcott implied that because of the slave trade, the greatest monument in the Antilles is perhaps the Caribbean Sea itself.

Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs?

Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,

in that grey vault. The sea. The sea

has locked them up. The sea is History.

If the ocean is a monument to all those African lives lost to European depravity and greed, the Haitian nation is a monument to how those same Africans could rise up against their oppressors and achieve freedom from slavery and independence from colonial rule.

“We think of history as human because our experience of time is very much predicated by memory,” Báez reminds us, “but the world around us has a longer history.” Caribbean history does not begin with Columbus’s arrival in 1492, any more than African history begins with the onset of the Portuguese and Spanish slave trades in the 1500s. Yet the idea that the Caribbean is a place without a knowable past remains. Cuban author Antonio Benítez-Rojo once sighed, “For it is certain that the Caribbean basin, although it includes the first American lands to be explored, conquered and colonized by Europe, is still … one of the least known regions of the modern world.” What Báez calls her “permeable” painting of the king of Haiti’s palace, stamped with old maps and covered in barnacles, forces visitors to contemplate interlocking strands of history and geography that tell the story of an America that stretches far beyond the United States.

You Might Also Like