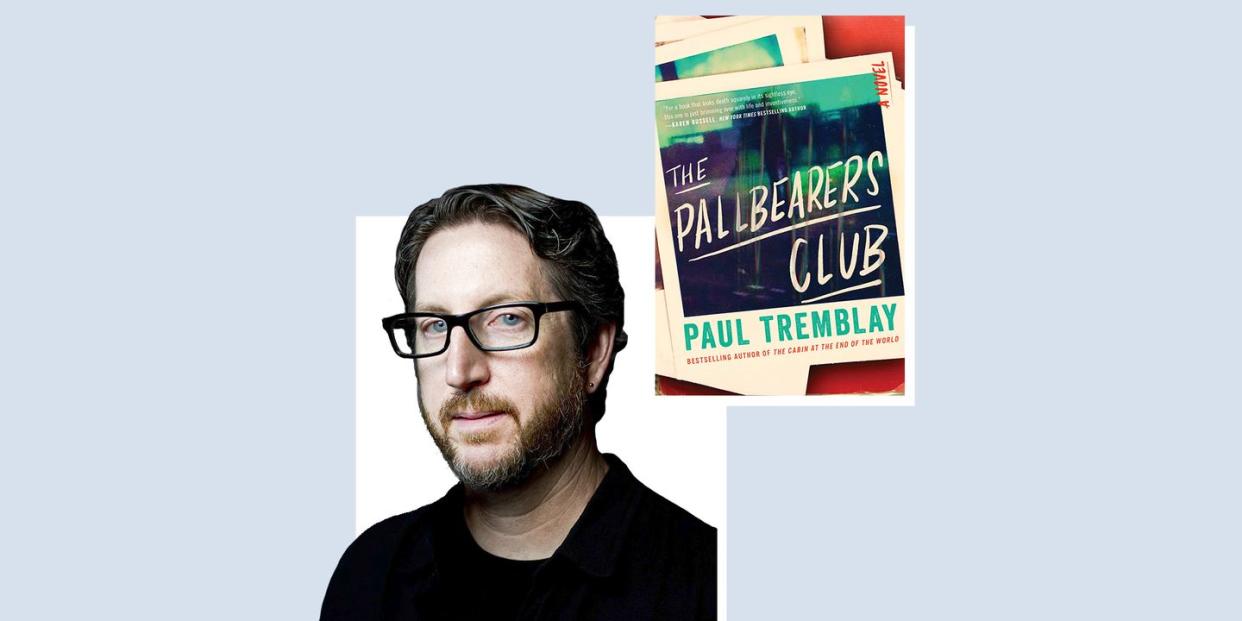

"I Read Horror to Be Who I Am": Inside Paul Tremblay's Terrifying Mind

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“I am not Art Barbara.”

This is how Paul Tremblay’s The Pallbearers Club begins: with a truth about a lie, or perhaps a lie about a truth. Either way, it’s a suitably slippery opening to the author’s latest novel, a tale of unhappy adolescence, punk rock, and… vampires? Trying to grasp the elusive ‘truth’ of Tremblay’s narrative is like clenching a fist around water.

Of course, uncertainty is Tremblay’s stock-in-trade. Over the last decade, he has grown from hot new thing to horror icon without compromising on his uniquely inexplicable nightmares. From the breakout success of A Head Full of Ghosts, with its zeitgeist-savvy take on demonic possession, to the cosmically-inclined home invasion shocker, The Cabin at the End of the World, and 2020’s Survivor Song—which so unnervingly predicted the impact of a lethal virus in the age of disinformation—Tremblay has consistently confounded resolution.

Now, with The Pallbearers Club, his commitment to ambiguity has only grown stronger. The novel presents as a faux-memoir, detailing the early-to-mid manhood of “Art Barbara,” an awkward teen with scoliosis, Marfan Syndrome, and terrible acne. In pursuit of extracurricular honors, Art established the titular Pallbearers Club, where he forms a friendship with the enigmatic Mercy. There are many questions to ponder; whether Mercy is an essence-draining vampire resurrected from local New England lore is only one of them, and not necessarily the most pressing. As Mercy creeps into the text through handwritten commentaries and margin notes, she deconstructs Art’s recollections with increasing acuity. The reader is forced to confront the unavoidable tension between fact and fabrication that underpins all fiction. Can we trust Art? He promises to be “painfully honest,” but how possible is such truth in the face of time and memory and too much self-analysis? And what horror can be mined from that unsteady ground?

These are the issues that I’m ready to discuss with Tremblay, a few weeks prior to publication. He flashes up on our video call in his son’s bedroom (where the Wi-Fi is best), surrounded by books and movie paraphernalia. It’s a fitting backdrop for a writer who has so persistently mapped the intersection of horror, media, and pop culture. I’m a little nervous. He is, after all, a teacher as well as a genre authority, and talking about his work feels a little like presenting the most taxing book report of all time. Thankfully, as on previous occasions when he and I have spoken, I get the sense that this is a mutual investigation—that even he has yet to delve into all the hidden folds of his stories.

We begin with something we can be sure of.

Before we even get to the uncanny and possibly supernatural elements of The Pallbearers Club, the very nature of the club itself is such a strange idea. Where did that come from?

I was lucky; that particular aspect of the story just fell into my lap. I work as a teacher in a high school and during Monday morning assembly, a senior student got up on stage and mentioned that he was starting this club to assist at the funerals of people who don’t have anyone else. The teacher in me thought that was a sweet thing to do, but the horror writer sat up straight when I heard the words "Pallbearers Club."

I had nothing beyond the title, but the more I thought about this student—he wasn’t one of the popular kids; he was quiet and a little shy—the more I thought about myself in high school and whether I would have done something similar. I thought, “I’m going to put my high-school self through this and see where it goes.” That gave me permission to look back and tell a story that takes place over decades, and maybe go a little bit more inward. Those things appealed to me.

There is an element of biography, then? The book opens with the narrator admitting that he is not who he claims to be. Is that because he is actually you?

I started with the notion that Art would represent me on a different life path. What would have happened, for instance, if I’d dropped out of college to play in punk bands? I always tend to start with some autobiographical question like that, and then I see where it goes. Of course, I’ve leaned into it much more heavily with this book. Striking the balance was the biggest challenge of the book by far. There were things that I wrote that seemed really clever, but then I had to tell myself, “Paul, no one will get this reference about that thing that happened that one time when you were fifteen.” In the end, it was broader stuff like music and family. Art has a very interesting relationship with his parents in this book, and a lot of that is drawn from my own high school years.

There's one moment between an adult Art and his mother when he describes how “we had to remind ourselves not to be so continually shocked at how old we were.” In a novel that is otherwise surprisingly light-hearted for you, that feels like a kernel of a familiar existential horror.

I remember writing that line. That was a moment where my pandemic life sneaked in. You think you’re writing about something else, but it creeps in there. My mother lives alone. She was shielding and we would speak each day by video call, but it was the first time that I really confronted our ages and our mortality. It’s the precise tone I wanted for the book, though; I wanted it to go inward and to go bleak.

Bleak is something you’ve done before, but that inward turn feels like a departure, especially compared to your last two novels.

Oh, agreed! The idea for this one came to me just as I was finishing the edits on Survivor Song. That book fulfilled my three book deal with William Morrow at the time. I was looking to perhaps take some time off because the writing of both that book and, before that, The Cabin at the End of the World, had been so intense. Those books were both so heavily engaged with the anxieties of the now. And both of those novels featured a highly compressed timeline—Cabin takes place in a single day, and Survivor Song covers just six hours. They have a thriller structure as a result, and I noticed that my publisher was really leaning into marketing my books as thrillers. Now, I’m not throwing shade on thrillers; I read them and enjoy them, but that’s not where my career-long interests lie. I want to be a horror writer.

What is the horror at play in this novel, then? Because it isn’t easily pinned down. What themes are you tussling with?

The horror of the self, I think. All of my books have been interested in that, I think. I’m fascinated by the ambiguity of our inner spaces: memory and identity and even reality itself. I think all of those are wrapped up in The Pallbearers Club, because even though Art spends so much time—basically the entire book—writing about himself, he remains a mystery to himself. I think there is both horror and humor in that realization. That’s the thin line that I was trying to walk.

And walk it you do. Because even though there is much darkness, this may be your first genuinely funny book.

Well, you can find some people who say that A Head Full of Ghosts is funny, though I wouldn’t have anticipated that. Obviously, horror and humor are so closely related—you can react to life’s absurdities by laughing ruefully or being terrified. I knew that I was going to be fairly brutal to the ‘me’ character, so I guess I wanted to cut that with some kind of humor as well. I’ve heard a lot of people talk about reading and writing as an escape. That’s not me. Reading is not an escape, and writing is work. But this was the first time that writing a book did offer some kind of way out of reality, even if it was into the past that I curated, and crafted, and fictionalized.

If reading is not an escape, what is it for you?

Something different. During the pandemic I stopped watching the horror and the stories that I normally love. I was watching Animal Planet just to shut my brain off. I felt unmoored from myself. Weirdly, what got me back to some semblance of myself was re-reading Peter Straub’s The Throat, which I don’t think anyone would describe as an escape book. But what I discovered was that I don’t read horror to escape; I read it to be who I am.

And what about music? Punk is very present in this book. Particularly the work of Hüsker Dü, a band I’d never previously heard of.

(A long, appalled pause). Hüsker Dü are my favorite band and the lead singer Bob Mould is my favorite musician. I’ve probably seen Bob perform over thirty times. More than even reading books, it was listening to Hüsker Dü and Bob’s later music that inspired me to create something myself. I learned to play guitar and I wanted to be a punk musician, even if it was in shitty bands. But it never happened and I figured I was a better writer than musician. Some of the music is still there in the fiction, though. That a story engenders a shared recognition of something being terribly wrong is a defiantly hopeful thing to me. I think punk has a similar raised-fist—a “we know we're doomed, but at least we know the truth” vibe.

But do we? It’s as if you have written this book specifically to deny us the truth, with Mercy deconstructing and undermining Art’s memoir from the margins.

I’m a sucker for new and interesting ways to present a narrative. That said, what remains key for me is that the form must not be a gimmick. It has to be tied to the theme of the story. The Pallbearers Club’s form felt like an extension of the story logic. This was a found memoir, which means someone needs to find it. From that point it became a way of developing character. Mercy not only found and read the memoir; she couldn’t resist commenting and analyzing. In a way, she becomes an editor of the document. That, in turn, adds further elements of ambiguity to the novel. Though I will say that I think Mercy is being honest in her commentary, perhaps even when Art isn’t.

That focus on unreliability pervades so much of your work. What is it about the nature of truth and our access to it that you keep returning to in your stories?

Well, who isn’t obsessed with truth? Especially in this age of misinformation when you have to invest so much more work into identifying what is true. But it’s also an issue of character. As a reader, I’m far more interested in fallible characters who make terrible mistakes and the decisions that led to those mistakes—decisions that were based on whatever information they had at the time. That’s the human part of fiction. It’s the human part of being human. That’s why I have a fondness for what I call the first-person asshole narrator. The kind of narrator who is not very good, but they are still trying. Books like William Kennedy Tool’s A Confederacy of Dunces. That kind of narrator tests my empathy, and my ability to connect with characters who are unsavory, or who make poor decisions.

You’re an author who generally eschews tropes, or you deconstruct them to the point where they're no longer recognizable. I was surprised to see you take on the vampire in The Pallbearers Club.

Actually, I feel like a lot of my books have taken on tropes head-on. A Head Full of Ghosts dealt with possession; Survivor Song is a zombie-adjacent novel. I just try different ways to approach them. For years, my friend [and fellow horror writer] John Langan has been asking me when I’m going to write my vampire novel, but I had no ideas. Then I discovered the legend surrounding Mercy Brown, this supposed vampire from New England folklore. I hadn’t heard of her until a very few years ago, but the legend does seem to have become more popular in the last decade.

What is the legend?

Most of Mercy Brown's rural Rhode Island family died from tuberculosis in the late 1800's, and Mercy herself died in 1892. The desperate and superstitious locals thought that Mercy was returning from her grave at night to feed and sicken family members suffering from what they called consumption. A small group gathered to exhume her somewhat freshly dead body, and found that her heart was full of blood. They removed it, burnt it. and had her brother drink the ash-heart slushy to cure and protect him. There’s a fascinating book called Food for the Dead by Michael E. Bell, which details this event and other similar exhumations within New England in the 18th and 19th centuries. Mercy’s grave is a somewhat popular visit these days. Anyway, that all felt like it offered a different run at vampire lore. It certainly isn’t a Bram Stoker-ish vampire in The Pallbearers Club, if the book contains any vampires at all. Even that’s up for debate.

The Pallbearers Club isn’t your only big news this summer. Word has gotten out that The Cabin at the End of the World is being adapted for the screen by M. Night Shyamalan. Is there anything you can tell us about the movie Knock on the Cabin?

I can’t and won’t say too much about the adaptation itself, except to say that it’s very exciting. I got to visit the set for a couple of days back in May and everyone was very enthusiastic. It was especially cool that all the actors had read the book. I think it’s going to be a beautifully acted, beautifully filmed movie. It is going to be very much M. Night’s vision of the story though.

This is where I continue to ask you questions and you continue to skillfully parry them, but what is it like to have your story in someone else’s hands?

Well, my first love, in terms of horror, was movies. Before I took to reading later, I learned about story through film, and as a writer who uses the influence of other books and other media, it would be highly hypocritical for me to have a problem with someone using my story to make something different. There is something very interesting in that to me, how someone can take the bones of a story and make something adjacent to it. Of course, no writer is ego-less, and it will be strange if and when there are differences between the two tellings—because it is sobering that once a movie is made, in the eyes of the wider culture, that IS the story. Millions of people will see this movie, compared to the few hundred thousand who have read Cabin.

I will say this though. I think this film is going to fuck people up.

What’s next from your pen?

Next year I’m publishing another short story collection. It’s called The Beast You Are, and because I so obviously know what the mainstream reading public wants, the title story is a 30,000-word anthropomorphic animal novella that features a giant monster and a cat that’s a slasher… oh, and it’s also written in free-verse.

So not everything is autobiographical then? After The Pallbearers Club, something occurred to me. Could you still write a biography? Is anything left?

That’s something that I worried about when I first finished the book. I have used myself a lot in my fiction. I told more than a few friends, “Man, I think I’ve emptied the bucket on this one.” But then you live more life and there is more there for you to use.

That said, this book does feel like a transition. I’m not sure towards what, but I spent my first few books writing about young families with young children, and there’s some of that in The Pallbearers Club, but it’s more focused on older families whose kids are grown. Both of my kids are going to be in college next year, so what am I going to write now? Empty nest horror? Whatever comes next, it’ll be different.

You Might Also Like