From Ravilious to Rothko: how looking at paintings can lift our spirits

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

We know that making art can reduce stress and improve wellbeing, but what if you could do the same by simply looking at it? In these difficult times, can reflecting on a painting, or a drawing, or a sculpture, cure us of fear and sadness?

The philosopher Alain de Botton thinks so: “Alongside religion, [art] has been humanity’s chief source of consolation,” he says. “There is no reason it should not continue to function in this way now.”

Certainly, scientific research conducted in the past decade tells us that experiencing awe – as you might looking at the Sistine Chapel, for example – triggers feelings of hope and fulfilment. It has also been proven that art can raise serotonin levels, literally changing the way you experience the world. (Paintings by artists Constable, Ingres and Monet produce the most powerful “pleasure” response, on a par with gazing at a loved one.)

Then there’s art’s positive effect on healing and pain tolerance. If you live in Montreal you can even be prescribed a museum visit by your doctor for eating disorders, epilepsy, mental illness and Alzheimer’s.

It helps that visual art is a language shared by all (except, perhaps, for the more conceptual), though you need to reflect on it in a particular way – forgetting all about its “meaning” or price, or place in the canon. “The squeamish belief that art should be for art’s sake has unnecessarily held back art from revealing its latent therapeutic potential,” says de Botton. Thinking about pictures that were painted hundreds of years ago might help you grasp that pain and suffering are a historical constant rather than specific to now.

Or, art might provide an antidote to the typically insular way we approach suffering. “We are often unhelpfully coy about the extent of our difficulties,” says de Botton. “We thereby end up not only sad, but sad that we are sad. All this, art can correct … lending legitimacy to despair and replaying our miseries back to us with dignity.”

What, then, might a therapeutic way of reading art look like? Here is a selection of works to point the way.

If you’re anxious

I’ve found some respite from a restless mind in still life. The pristine paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, with their jewel-like objects and velvet dark backgrounds, are a gold mine. Three Peaches on a Stone Ledge with a Red Admiral by Adriaen Coorte (1660-1707) is my current favourite, but William Nicholson’s The Lustre Bowl with Green Peas (1911) is a close second.

De Botton also suggests seascape photographs by the Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto. “We are afforded a glimpse of what the planet looked like before the first creatures emerged from the seas,” he explains. “We regain composure by being reminded of the minuscule and momentary nature of everyone and everything.”

If you’re fearful this will never end

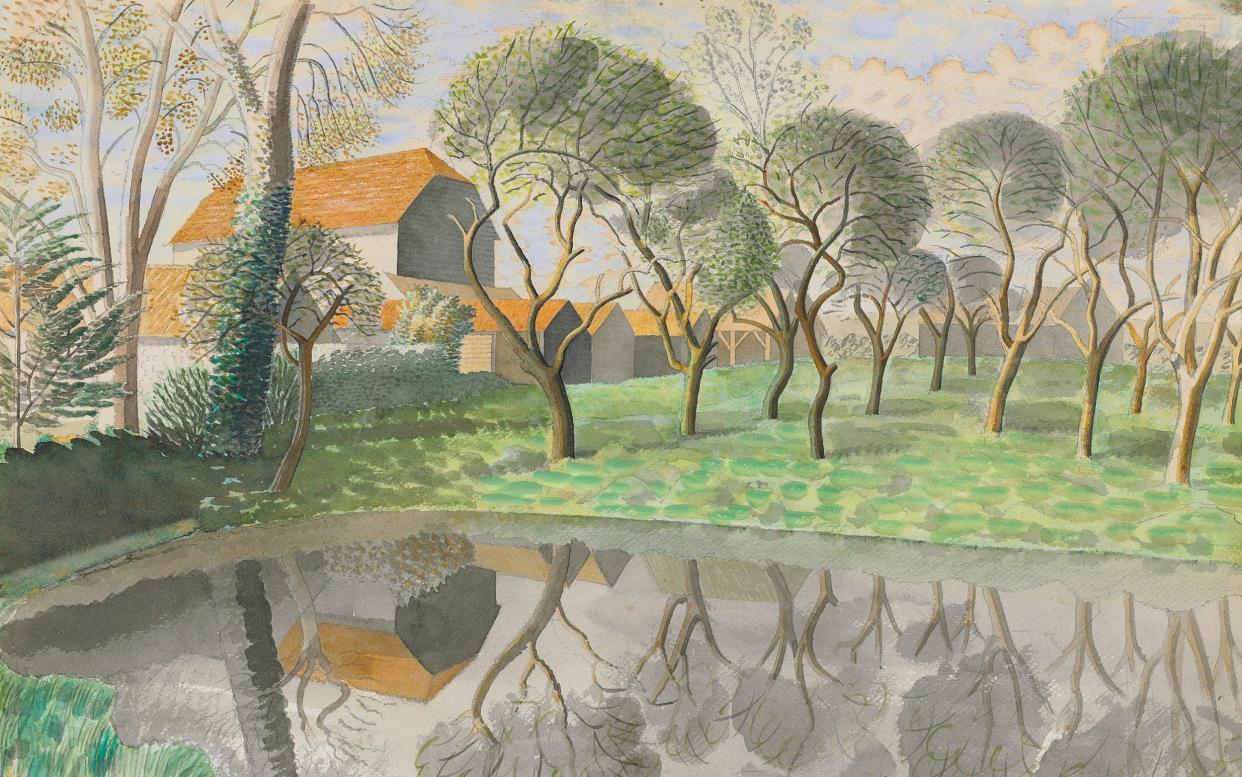

Look how hungrily we leapt upon David Hockney’s new iPad paintings of daffodils and blossoming trees, when he released them, a week into lockdown, with the title Do Remember They Can’t Cancel Spring. Seems ages ago. But the message is still relevant: life (and art) go on. We might also learn from the generation of British artists exposed to the horrors of the First World War, many of whom found comfort in the possibility for renewal offered by a garden.

Eric Ravilious is a good place to start, though I also recommend the work of Charles Mahoney, who drew such joy from the sight of his garden that he set up a mirror in his living room, to perfectly reflect its ever-changing tones and textures.

If you’re finding life mundane

I’ve lost count of the times someone has moaned to me about the bore that cooking and cleaning have become. “It can be hard to see beauty and interest in the things we have to do every day,” agrees de Botton, adding that art can, “usefully reconcile us to the unavoidable imperfections of existence”. Your best medicine is genre paintings: elegant, highly detailed pictures of people attending to their daily rituals.

De Botton uses At the Linen Closet (1663) by Pieter de Hooch as an example. “The linen closet itself could easily be resented. It is an embodiment of what could be seen as boring, banal… but the picture moves us because we recognise the truth of its message. If only, like de Hooch, we knew how to recognise the value of ordinary routine, many of our burdens would be lifted.”

If you need help appreciating your more restricted life

“One of our major flaws as animals, and a big contributor to our unhappiness, is that we are very bad at keeping in mind the real ingredients of fulfilment,” de Botton says, adding that advertising has much to answer for. “We’re deeply ungrateful towards anything that is free or doesn’t cost very much, we trust in the value of objects more than ideas or feelings.”

Your antidote consists of thinking of artists as running a different kind of campaign. “In the 1830s, the Danish artist Christen Kobke did a lot of advertising for the sky, especially just before or after a rain shower,” says de Botton, while “the American painter Mary Cassatt made a good case for the world-beating importance of spending some time with a child”. Presumably not while having to home-school them, though.

If you need a shot of courage

In the 17th-century heyday of the Dutch republic, artists such as Willem van de Velde (elder and younger) and Ludolf Bakhuizen made a fortune depicting ships in storms. “These works were not mere decoration,” says de Botton. “They had an explicitly therapeutic purpose: delivering a moral to their viewers about confidence in seafaring and life more broadly. What is true of storms in the North Sea may be no less true of the turmoils in our lives,” he adds. “The storms will die down, we will be battered, a few things will be ripped, but we will eventually return to safer shores.”

If you need a good cry

We often refer to sad music or films as cathartic. Yet few would think of the visual arts like this. Perhaps we should. People used to. The 18th-century French philosopher Denis Diderot urged artists to “move me, astonish me, unnerve me, make me tremble, weep, shudder, rage, then delight my eyes afterwards if you care to”. Paintings by the abstract expressionist Mark Rothko are most frequently referred to as tear-jerkers, though Jean-François Millet’s 1857 The Gleaners painting apparently made 19th-century viewers sob.

If you like your melancholy in more contemporary form, de Botton suggests Anselm Kiefer’s Alkahest (2011). “Its icy, grey, harsh character summons up equally grim thoughts about our own lives,” he says. Painful, yes, but through the pain comes a sort of strength.

Art as Therapy by Alain de Botton and John Armstrong is published by Phaidon