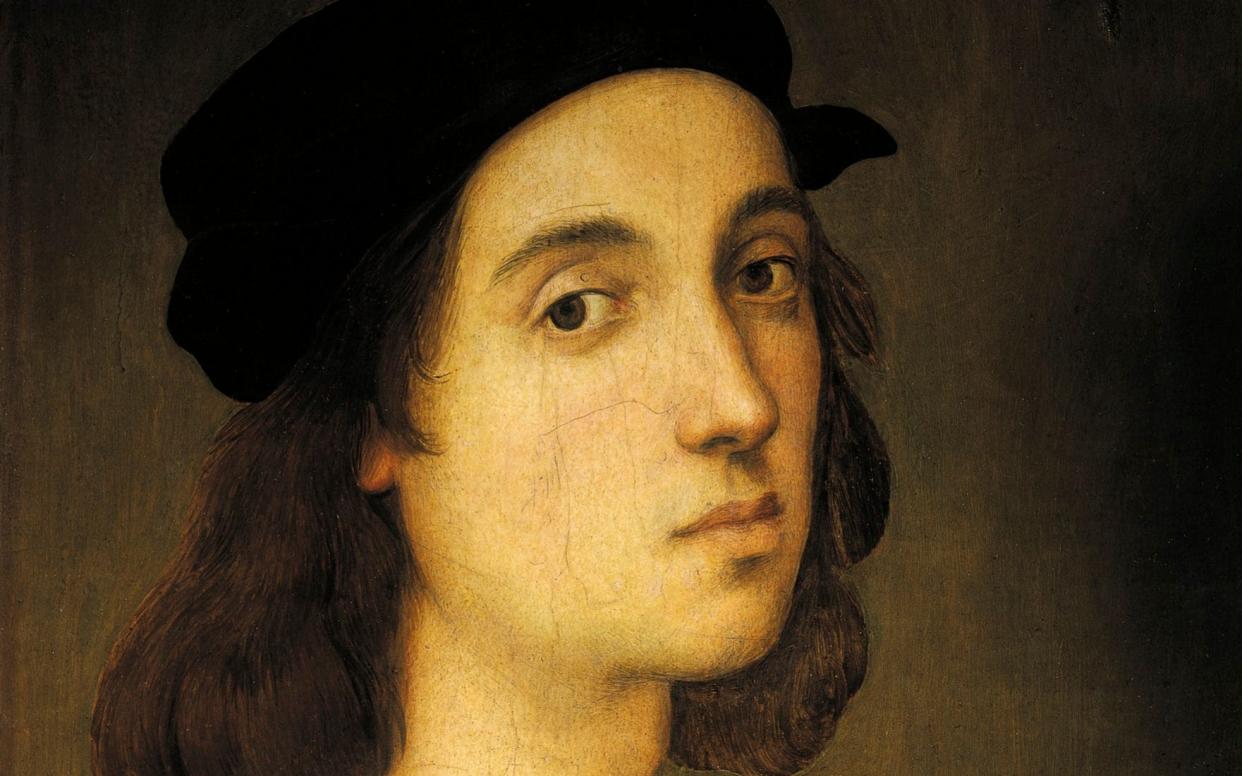

Raphael: artistic god or purveyor of kitsch?

As we emerge from lockdown, the art world, like many spheres, is awash with anxiety. How will museums and galleries cope with reduced budgets and restricted travel? Everyone agrees that the blockbuster exhibition may – temporarily, at least – become a thing of the past.

So, it is with the air of one last hurrah that on Tuesday, the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome reopens its exhibition marking the 500th anniversary of the death of the Italian artist Raphael (1483-1520). At last, the “once-in-a-lifetime” marketing hype feels justified. Forced to shut within days following the imposition of Italy’s lockdown, the show was the centrepiece of various high-profile Raphael exhibitions planned for 2020 – including one at London’s National Gallery, which has been pushed back by a couple of years. Thankfully, the Rome exhibition has been extended, to the end of August. For now, though, due to recently announced quarantine measures for travellers, Britons will have to make do with a 13-minute virtual tour on YouTube.

Beginning at the artist’s death, with a dramatic recreation of his tomb in the Pantheon, the show has an ingenious conceit: it proceeds in reverse through Raphael’s life. Shaking up preconceptions, it reminds us that, arguably more than any other giant of the High Renaissance, Raphael remains somewhat misunderstood.

For centuries, Raphael occupied the pinnacle of Western painting, beloved by big-league artists from Poussin to Ingres. His oeuvre became the bedrock of art academies across Europe. Fifty years ago, though, in his television series Civilisation, Kenneth Clark summed up a profound shift in taste that had occurred in the preceding decades. Introducing Raphael, he described him as “the supreme harmoniser – that’s why he’s out of favour today”. Clark’s words encapsulated what became the clichéd view of Raphael – that he had little to offer a century benighted by catastrophe. All those graceful visions of the Virgin and Child, which Raphael painted mostly in Florence at the start of the 16th century, before he was summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II in 1508, seemed somehow inadequate in the epoch of mechanised warfare and the Holocaust. Where, in Raphael’s work, was life’s discord, violence, turmoil? Wasn’t the polished sweetness of his painting, so vaunted since Vasari, in fact sentimental and ingratiating?

It is true that, during the 20th century, as modernism gleefully savaged academicism, and formerly time-honoured values such as beauty and harmony fell out of favour, Raphael slipped slightly in the estimation of art historians and critics – though not, of course, Clark, that arch-traditionalist. Still, I have always found Clark’s follow-up in Civilisation – “One couldn’t write a bestseller about Raphael” – unfair. OK, only a handful of letters by Raphael have survived, so we will never fathom the artist’s inner life as we can with, say, his great contemporary Michelangelo (who abhorred his younger rival). Moreover, Raphael’s modesty, gentleness, and “graceful affability”, as described by Vasari, are not exciting character traits for any modern biographer.

Yet, Raphael, the son of a painter, who grew up at court in Urbino, enjoyed astonishingly swift success. He ended up, by his mid-30s, as the pre-eminent artist in Rome, unscathed by the back-stabbing endemic in any epicentre of power. Other than Michelangelo, barely a soul had a bad word to say about him. The chief minister of Julius’s successor, Pope Leo X, even offered Raphael, a close friend, his niece as a wife.

As well as a rollicking narrative (Netflix executives, take note), Raphael’s meteoric success provides a clue to his true nature. What lay beneath the velvet glove of his gentle manner? Iron ruthlessness, surely. Then, there’s all the tittle-tattle in Vasari about the amorousness of this good-looking youth, who loved the company of women. One powerful patron even persuaded Raphael’s mistress to stay with the lovesick artist in a palace he was decorating so that he would finish the job. Indeed, the story of Raphael’s death, as told by Vasari, from a fever supposedly caused by excessive lovemaking, is the stuff of romantic fiction. Dramatising his life, then, requires only a smidgen of imagination and poetic licence.

What, though, of Raphael the artist? Well, he was much more than a painter of sugary madonnas. “There’s always something surprising with Raphael,” says Matthias Wivel, co-curator of the National Gallery’s postponed exhibition. As well as decorating the “Stanze” of the papal apartments in the Vatican Palace, which occupied him for years, Raphael excelled in architecture. (On Bramante’s death in 1514, he was appointed architect of St Peter’s.)

He designed tapestries depicting the Acts of the Apostles for the Sistine Chapel (the surviving cartoons for which are on long-term loan at the V&A) and ended up running a large workshop for which demand never slackened. He was a brilliant draughtsman, as a magnificent exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford revealed a few years ago. Oh, and he even wrote poetry.

As the Raphael scholar Hugo Chapman put it in a recent, excellent episode of The Art Newspaper’s weekly podcast: “That entrepreneurial spirit of Raphael, this idea of him sitting in the centre of his studio as the chief designer of a variety of different lines, is very modern. If Raphael were alive today, he would be a film director at the same time as writing a novel. He was extraordinarily creative.”

According to the art historian Angelamaria Aceto – who worked on the Ashmolean show, and has been involved with the exhibition in Rome – Raphael was “one of the greatest storytellers of all time”. In his frescoes at the Vatican, Raphael was able, she says, to capture “people’s attention and heart in the same way a movie would”.

All that success, incidentally, may have done him in: by his mid-30s, he must have been under immense pressure professionally. Perhaps burn-out, rather than too much sex, precipitated his early death.

Another sign of Raphael’s modernity was his interest in printmaking, which he recognised would widely disseminate his ideas. Unlike Michelangelo, “Raphael actively engaged with printmakers and publishers,” says Aceto. “So, yes, he was sweet and kind, but also astute and opportunistic – in a way that Michelangelo was not.”

Ultimately, though, Raphael’s reputation still rests on his paintings. And today, it is arguably his portraits that resonate the most – especially with a British audience for whom Catholic imagery of the Holy Family isn’t ingrained. Raphael’s supposed tendency to refine reality is confounded by portraits such as that of his friend Cardinal Tommaso Inghirami, who had a squint. “In this portrait, there is no idealisation of the face,” points out Aceto. “The skin is not perfect. Raphael does not change the defect in the eye.”

For Wivel, too, Raphael’s portraits, albeit often “very flattering”, are among “the most penetrating of the period”. He describes the National Gallery’s likeness of the warmongering Pope Julius II – which became the model for papal portraiture for two centuries, and makes me think of a disconsolate Santa, slumped after the exertions of Christmas Eve – as “astonishing”: “Somehow, Raphael manages to make him appear monumental, but also frail and melancholy. It’s a deeply weird, introspective portrayal of a very powerful man – Raphael picks up on an essential humanity.”

Meanwhile, Raphael’s portrait of Leo X, the profligate Medici pope who supposedly said: “Since God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it”, is compelling in a different way. “He looks like a Mafioso,” says Wivel, “the head of the church, but the centre of profane power. There’s a sinister edge to that picture. Raphael shows us the brutality that comes with power.”

Given the scope of Raphael’s output, and his long-lasting standing within Europe’s art academies, you could argue that he exerted even greater influence than Michelangelo. Which is astonishing, given that he wasn’t yet 40 when he died. (Michelangelo lived until he was 88.) “This is a fundamental thing that we tend to forget,” agrees Aceto. “Had Raphael lived longer, God knows what would have happened.”

Raffaello 1520-1483 reopens on June 2 and runs until Aug 30. Information: scuderiequirinale.it. To watch the ‘Walk in the Exhibition’ online tour, go to the museum’s channel on YouTube