Racist or misunderstood? The fight for Adolph Rupp's legacy

The second Black basketball player in University of Kentucky history stood outside Adolph Rupp’s office door trying to summon the courage to knock.

Reggie Warford needed the answer to a question that had bothered him since Rupp began recruiting him.

It was 1972, 18 years after the Supreme Court issued its landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling rendering segregation illegal in public schools. Kentucky began accepting Black undergraduate students in 1954 and opened its athletic programs to students of color nine years later, yet Rupp’s basketball program remained almost exclusively white.

Warford sought to better understand why so many of the region’s premier Black players of his era either didn’t hear from Rupp or passed on the chance to play for him. After entering Rupp’s office and making small talk for a few minutes, the 17-year-old incoming freshman boldly asked the architect of Kentucky’s basketball dynasty, “Why didn’t you recruit more colored players?”

The response from Rupp struck Warford as authentic yet leaving much open to interpretation.

“Because I didn’t have to, son,” Warford recalled Rupp saying. “I’ve always gotten the best white players in the country.”

Almost a half century later, Rupp’s attitudes and actions on the issue of race remain a subject of interest and controversy. At stake is the legacy of a coaching icon who captured four national titles and never endured a losing season in 42 years as patriarch of one of college basketball’s most tradition-rich programs.

To some Americans, Rupp is a symbol of the Segregated South, a villain who spoke in racial slurs and stood in the way of change. Those critics view Rupp through the prism of the 1966 national title game in which his all-white Kentucky team famously lost to a Texas Western squad with five Black starters

Rupp’s defenders in the Bluegrass State see a very different “Man in the Brown Suit” than the caricature painted by his critics. Supporters of Rupp argue his racism has been exaggerated, his progressive contributions have gone overlooked and his reputation as a segregationist is at best misinformed.

The faculty members in Kentucky’s African American and Africana Studies department reignited the debate anew in July when they proposed changing the name of Rupp Arena. In a letter sent to University of Kentucky president Eli Capilouto, the faculty members argued that Rupp’s name “has come to stand for racism and exclusion” and “alienates Black students, fans, and attendees.”

So who really was Adolph Frederick Rupp? What, if anything, did he do to benefit Black players during the Civil Rights era? How much more could he have done? Finding the answers requires stripping away the mistruths that have accumulated over the years and freshly evaluating one of the most complicated and compelling figures in basketball history.

Adolph Rupp heads to Kentucky

In late August 1930, an ambitious 28-year-old Illinois high school basketball coach packed up a few belongings and drove South to take on a new challenge. The whole time he wondered if he had made a mistake accepting an offer to become the basketball coach at a university that until then had shown only indifference to the sport.

The Kentucky job paid only $2,800 per year, exactly what Rupp made as the coach at Freeport High School. In addition to coaching the basketball team, Rupp’s position also required him to serve as an assistant for the football and track and field teams.

In those days, the facilities or fan support weren’t exactly what John Calipari enjoys today either. Kentucky played in a cramped, $92,000 gymnasium Rupp considered no better than the one at Freeport.

Further complicating Rupp’s decision whether to take Kentucky’s offer, he had begun dating his future wife in Freeport. Rupp had also just earned his master’s degree and principal’s diploma and his future as a high school coach and administrator was bright.

The principal at Freeport High School encouraged Rupp to stay. Others in Freeport echoed that, calling Lexington “hillbilly country” and telling Rupp “whoever heard of Kentucky doing anything [in basketball]?”

Rupp changed that in a hurry once he took the Kentucky job — and he did it by recognizing ahead of his time that a lethal fast-break attack was key. In Rupp’s debut, Kentucky trampled outmanned Georgetown College, 67-19. His teams continued to run like hell for the next four decades, amassing an 876-190 record and 27 conference titles.

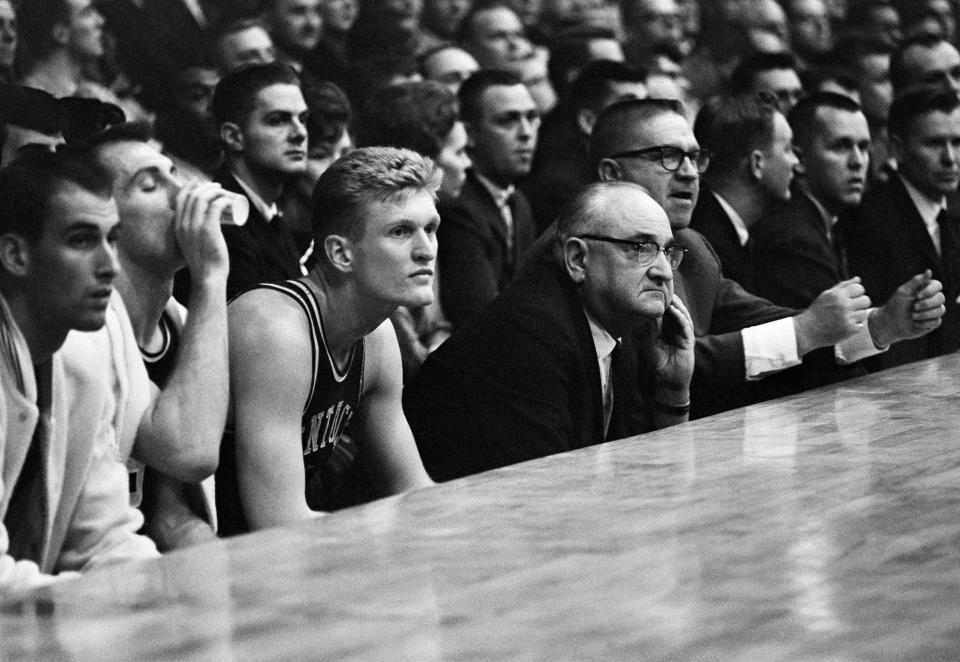

A sharp-tongued disciplinarian and notorious perfectionist, Rupp was seldom chummy with his players yet he possessed an innate ability to draw their best out of them. Nobody else dared make a sound when Rupp addressed his teams. The locker room was Rupp’s stage, as was the practice floor.

On Jan. 8, 1945, Kentucky led an overmatched Arkansas State team 34-4 at halftime. Rupp infamously burst into the locker room demanding to know which of the Wildcats was guarding the opposing player who had scored all of Arkansas State’s points because he was “running absolutely wild.”

Years later, with Kentucky sleepwalking through an early-season practice, Rupp shouted for his student manager to get a towel. “The roof must be leaking,” former manager C.B. “Mike” Harreld recalls Rupp bellowing. “There’s a drop of water on the floor and none of these blankety-blank blankety-blanks are working hard enough to sweat.”

Fame was the only thing Rupp liked as much as winning, so he courted it unabashedly. In his early years at Kentucky, he’d siphon attention away from football by hyping almost every game his team played as part of a bitter feud. Later, when his Sunday night TV show was appointment viewing across Kentucky and photos of him posing with celebrities littered the walls of his office, reporters who approached Rupp for a splashy quote seldom came up dry.

After a New York writer asked him to suggest some rule changes to improve the game, Rupp outlandishly proposed reintroducing the center jump after made baskets, removing the net and backboard from the hoop and raising the baskets by five feet. Later, someone asked Rupp if he really liked those ideas. Replied Rupp: “Hell, no. But anything for a column.”

The success of Kentucky basketball under Rupp became a much-needed wellspring of pride for a rural state that lagged behind its neighbors in terms of industry and wealth. Kentuckians loved Rupp, and he embraced his adopted home state right back, his drawl seemingly deepening annually along with his affinity for good bourbon.

By the dawning of the Civil Rights movement, Rupp had as much political clout as any figure in Kentucky. The only question was whether he had any desire to push for change.

Rupp’s complicated legacy

Decades before the integration of Kentucky basketball, Adolph Rupp actually coached two Black players.

The first was William Moseley, a member of Rupp’s 1927 and 1928 teams at Freeport High. The second was former UCLA center Don Barksdale, who played for Rupp in 1948 when he became the first African American to make the U.S. Olympic basketball team

In March 1948, the U.S. Olympic committee staged an eight-team tournament to determine its roster for the London Games the following summer. The head coaches and starting fives from both Kentucky and the Phillips 66 Oilers earned the right to represent the U.S. after both teams advanced to the title game. Barksdale was among the committee’s four at-large selections.

In a 1991 interview with the LA84 Foundation, Barksdale said, “I started out with a very stormy relationship with Adolph Rupp.” Barksdale died of throat cancer in 1993, but one of his sons elaborated to Yahoo Sports about the icy reception his father got from the Kentucky coach.

“As the story was told to me, Adolph Rupp was initially opposed to the fact that my father was on the team because of his color,” Derek Barksdale said. “The initial communication was not there. He would always speak through another player to talk to my dad. He would never talk to my dad directly.”

When the U.S. team visited Lexington for an intrasquad exhibition game, Barksdale couldn’t stay with his teammates at a hotel. He instead stayed at the home of a prominent Black family, where he received a phone call from an unidentified man threatening to kill him if he played in the game the following night.

Shaken but not defeated, Barksdale suited up anyway, scoring 13 points while becoming the first African American to play against Kentucky in Lexington. The coaches subsequently gave Barksdale ample playing time during the Olympics and the 6-foot-6 center rewarded them by emerging as one of the gold medal-winning team’s best all-around players.

By the end of the trip, Barksdale appears to have won Rupp’s respect. In a 1984 interview with a Philadelphia newspaper, Barksdale claimed that Rupp “turned out to be my closest friend on the team.” In 1991, Barksdale told the LA84 Foundation that Rupp waited for him on the gangplank at the end of their voyage from London to New York to tell him “it was a pleasure” coaching him.

“That was something my father took pride in,” Derek Barksdale said. “He would always tell me that if he was dealing with a racist, he wanted them to have to question their racism by the time they were done speaking with him.”

It would make for a tidier story if Rupp emerged a changed man after getting to know Barksdale, but the truth isn’t so simple. In reality, Rupp’s subsequent treatment of African Americans ran the gamut from kindhearted to deplorable.

Sometimes Rupp was generous. In a 2018 documentary, NBA pioneer Jim Tucker revealed that Rupp approached him after a 1950 high school playoff game and told him he wished he were allowed to sign him. Rupp then went out of his way to recommend the African American to a friend who coached at Duquesne, paving the way for Tucker to become a two-time All-American with the Dukes.

Sometimes Rupp was open-minded. Seeking to challenge his teams against strong competition, Rupp did not dodge integrated non-league opponents the way some of his peers did. Teams with Black players visited Lexington as soon as 1951, more than a decade sooner than some of Kentucky’s Southeastern Conference rivals.

Sometimes Rupp was slow to act. In 1956, the state of Louisiana responded to Brown v. Board of Education by passing a law that prohibited Blacks and Whites from participating in the same athletic contest. Dayton, St. Louis and Notre Dame protested by backing out of a four-team Christmas basketball tournament in New Orleans, but Kentucky chose to honor its contract and Rupp helped find three all-white Southern teams to serve as replacements.

Sometimes racism came back to haunt Rupp. In the quarterfinals of the 1950 NIT, Kentucky’s opponent was a City College of New York team that started three African Americans. According to a book published last year by Matthew Goodman, the City College starting five each extended their hands just before tipoff but three Kentucky players turned away. Incensed by the snub, City College stormed to an 89-50 upset.

Too often Rupp was quoted using unforgivable racial slurs. In one such instance brought to light by James Duane Bolin’s 2019 Rupp biography, the Wildcats had just received silver belt buckles as a runner-up prize following a loss to Saint Louis in the 1948 Sugar Bowl tournament title game. Rupp allegedly burst into the locker room, hurled his belt buckle against a wall and said, “I wouldn’t give that to my n---- on the farm.”

It was a moment that hinted Rupp was ill-prepared for the long-overdue period of change in the South that was about to arrive.

Rupp told to integrate

In a meeting with a journalism class in December 1961, then-University of Kentucky president Frank Dickey made a headline-grabbing prediction.

Dickey said it was only a matter of time until African Americans began competing in the all-white Southeastern Conference and expressed hope that Kentucky would be “one of the leaders in bringing this about.”

The first obstacle delaying the integration of Kentucky athletics was the university’s conference affiliation. Many members of the all-white Southeastern Conference at that time were unwilling to schedule an integrated opponent. As a result, Kentucky risked having to leave the SEC if it desegregated its athletic department in the early 1960s, a financial hit that Dickey was not yet willing to endure.

In May 1963, shortly after polling fellow SEC members on whether they would agree to face integrated teams at home and on the road, Dickey decided Kentucky should wait no longer. The university became the first SEC member to declare its athletic teams were open to prospective students of all races.

The timing of Kentucky’s announcement coincided with the most pedestrian stretch of Rupp’s illustrious coaching career. Three times from 1959-65, Kentucky did not advance to the NCAA tournament. Twice more the Wildcats made the NCAA tournament field but failed to win a game.

Newfound access to the region’s premier Black prospects seemingly had the potential to help Kentucky reclaim its elite status, but Rupp complained that he couldn’t find impact players possessing proper academic qualifications. In a 1977 interview, Dickey recalled Rupp telling him, “I’m perfectly willing to have Blacks on the team, but the ones that I can get would never play and the ones that I want you won’t admit.”

Unwilling to waste a roster spot on an unproductive player, Rupp also warned that he would not lower his standards just to integrate his roster. To Rupp, the player who broke the Southeastern Conference’s color barrier had to be an immediate starter, a Jackie Robinson-esque figure possessing a blend of talent, intelligence and mental toughness.

When Dr. John Oswald replaced Dickey as university president in late 1963, he quickly grew tired of Rupp’s selectivity. He pressured Rupp to integrate the university’s highest profile program as quickly as possible, even if it meant taking a player who wasn’t an African American Cliff Hagan or Ralph Beard.

“Get someone,” Oswald told Rupp. “I don’t care if he sits on the bench.”

“I don’t recruit that way,” Rupp responded. “When I recruit, I'm going to get someone that can play.”

Following one such particularly heated meeting with Oswald, a livid Rupp returned to his office and chatted with longtime assistant coach Harry Lancaster.

“Harry, that son of a bitch is ordering me to get some n----- in here,” Lancaster recalled Rupp saying in his 1979 book, “Adolph Rupp: As I Knew Him.” “What am I going to do? He’s the boss.”

Rupp tries to integrate ... or did he?

The first Black prospect that Rupp deemed worthy of a scholarship offer was a future five-time NBA all-star and Finals MVP.

Six-foot-7 center Wes Unseld was a state champion at Louisville Seneca High in 1963 and 1964 and one of the nation’s most coveted recruits.

Softspoken and studious away from the basketball floor but a ferocious rebounder on it, Unseld would have been an ideal candidate to integrate the SEC. Kentucky players of that era describe him as the missing piece on Rupp’s Runts, the 1965-66 team that advanced to the national title game with no player taller than 6-foot-5.

One factor that led Unseld to pick Louisville over Kentucky was Rupp’s hands-off approach to recruiting. Rupp made just one visit to the family’s Louisville home and spoke only to Unseld’s parents because the player had a scheduling conflict.

Unseld didn’t know that in those days Rupp seldom bothered to leave campus to sell prospects and their parents on Kentucky, that he never even went to see the likes of Dan Issel in person as a high school player. As a result, Unseld perhaps mistakenly viewed Rupp’s style as a sign the coach didn’t actually want him and only made a show of recruiting him to please Kentucky’s pro-integration administration.

“Everyone at my high school and around kept saying that if they really wanted me, I would have talked to Rupp and heard from Lancaster,” Unseld said in the 2005 documentary Adolph Rupp: Myth, Legend and Fact. “You know, they would have been on my doorstep.”

Butch Beard, the state player of the year in Kentucky in 1965, was the second African American prospect that Rupp targeted. The 6-foot-3 guard had grown up listening to Kentucky games on the radio, a medium that allowed Beard to aspire to play for an all-white program.

Rupp’s in-home visit with the family went smoothly until the coach made the mistake of telling Beard’s mother that Kentucky might be academically challenging for her son. Recalled Beard with a laugh, “My mama said afterwards, ‘He must think we’re idiots!’”

In the eyes of Mama Beard, that wasn’t Rupp’s only blunder. He also didn’t sufficiently reassure her after she asked if he could keep her son safe when Kentucky played SEC road games.

The SEC’s Deep South footprint caused Kentucky to make annual visits to places where violent acts against Black people were common during the Civil Rights era. Black players also couldn’t stay in the same hotels, eat at the same restaurants or drink from the same fountains as their white teammates in many of those Southern cities.

Rupp was not naive to the danger, not after receiving boxfuls of handwritten letters threatening his life if he dared integrate the SEC. The Kentucky coach was likely just being honest when he promised Beard’s mother only that he’d do the best he could to protect her son.

When Rupp left their home, Beard’s mom told him, “You’re not going there.” Beard eventually gave in, following his friend Unseld to Louisville rather than being the one to break the color barrier in the SEC.

“I just didn’t feel like fighting that fight, to be honest,” Beard told Yahoo Sports.

Another swing and a miss on an elite African American recruit increased the pressure on Rupp to find a trailblazer. So did subsequent failures to land Black prospects Perry Wallace, Jim McDaniels and Felix Thruston, among others.

Over the next few years, Oswald’s impatience turned to anger. Vanderbilt had signed Wallace in 1966 and integrated SEC basketball a year later. In-state schools Louisville, Murray State and Western Kentucky had all featured integrated basketball teams for years.

“Basketball is the last segregated department that we have here in the university,” Oswald told Rupp.

Responded Rupp, “We made an effort to go get these boys, and we haven't been able to get them."

It’s reasonable to argue that Rupp dragged his feet in the recruitment of African Americans, yet it’s also clear that by the mid-1960s he understood the direction college basketball was headed. In January 1966, he gathered his players at the end of practice and told them to go home and read the newspaper because there was something in it that they would never see again.

“We were all looking at each other like has the old man gone crazy?” Harreld recalled. “Then he said that the top three teams in the country — Duke, Kentucky and Vanderbilt — were all from the South and all white. He said, ‘You’ll never, ever see that again.’”

Rupp lands his first Black player

The first Black player to play for Rupp at Kentucky admits he was emotionally ill-equipped for the challenge.

Thomas Payne hadn’t been a target of racism before college, nor did the 7-footer understand how much vitriol he would soon endure.

The son of a career Army man, Payne had lived all over the world before his family settled in Louisville when he was 15. The color of Payne’s skin was also a non-issue at the integrated high school he attended in Louisville, further shielding him from racism.

Tall, gangly and awkward as a child, Payne was a loner throughout school. Only after the coach at Louisville’s Shawnee High persuaded him to try out for the school’s basketball team as a sophomore did he realize that his height could be an asset.

From that point on, Payne’s ascent was startlingly fast. Teammates poked fun at him when he began playing basketball. Payne described himself as “this big string bean kid” who “couldn’t chew bubblegum and dribble a basketball at the same time.”

Only two years later, he was the most heralded player in one of American’s premier basketball states. He averaged 25.8 points and 29 rebounds as a senior and college coaches from across the nation wanted him.

Out of dozens of options, Payne chose Kentucky in June 1969 over the objections of some prominent Black people in the Louisville community. Beard said he cautioned Payne, “You don’t need to go up there. You don’t need that.”

“He just wasn’t mature enough to deal with it,” Beard said. “To be the first in a situation like that, you have to be special. It’s not for everyone.”

When Payne signed with Kentucky, Rupp predicted he’d have a Lew Alcindor-like career. Rupp continued hyping the 7-footer even as he was playing for a local AAU team as a freshman while getting his grades in order.

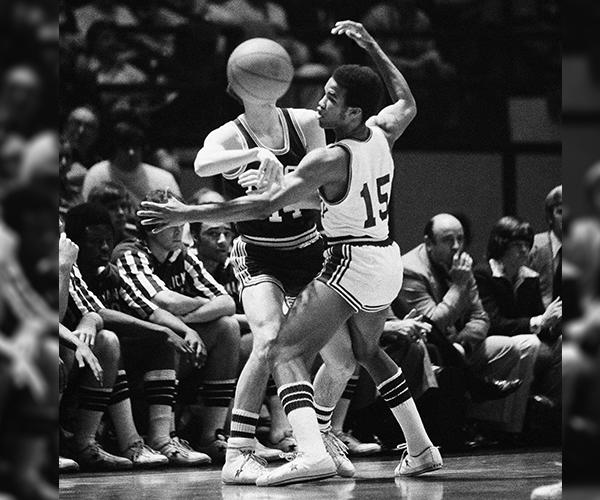

Payne became eligible to play as a sophomore in 1970 and beat out fellow centers Jim Andrews and Mark Soderberg for Dan Issel’s old starting job. Showcasing impressive skill and strength, he averaged 16.9 points and 10.1 rebounds, led Kentucky to a conference title and became the first Black player to earn all-SEC honors.

Though Payne lauded Rupp’s “courage” for starting him against the objections of others around the program, the former Kentucky standout admits the season took a toll on him because of the racism he endured. On campus Payne said that many white students ignored him or refused to interact with him. Then when Kentucky went on the road in the SEC, the abuse became more overt.

In Knoxville, someone scribbled on the blackboard in Kentucky’s locker room, "Payne — just a n-----!" Elsewhere, anything from racial slurs to cups of water rained down on him. There were also letters with Kentucky postmarks telling him he wasn’t wanted — or worse.

“It was really hard for me,” Payne told Yahoo Sports. “There wasn’t a whole lot of prepping emotionally for what I would go through, how the crowd would respond to me. I also didn’t really have anyone to talk to when I faced certain situations of racism and rejection. I had to internalize a lot of things. I was Black and everyone else was white. I didn’t know how to emote and talk and articulate my feelings. I was supposed to be this Superman and I definitely wasn’t. I was still a young kid inside.”

The pioneer that Kentucky had waited so long to find lasted just one season. Payne quit college to sign with the Atlanta Hawks at age 20.

“I didn’t feel accepted at Kentucky and I didn’t think I would be accepted,” Payne said. “And then economically I didn’t come from much. I thought the contract presented to me would help me and my family.”

The gamble didn’t work out for Payne. He lasted just one season with the Hawks and has spent much of his adult life in prison as a result of multiple rape convictions.

Like most former Kentucky players, Payne didn’t have a buddy-buddy relationship with Rupp. Their conversations were polite and respectful, but Payne never thought of him as a friend, just as a coach.

Now paroled and living in Michigan, Payne has dedicated his life to helping others cope with racial injustice and achieve racial conciliation. He feels a sense of pride at opening doors for Warford and the many other Black players who followed him at Kentucky.

“I look back fondly on Coach Rupp because I think it took a lot of courage for him to start me,” Payne said. “If he hadn’t started me, I wouldn’t have been able to show that a Black person can play at the level I did in the SEC.”

‘I’d hate to have my enemy decide my legacy’

Two days after faculty members in Kentucky’s African American and Africana studies program called for Rupp’s name to be stripped from the basketball arena, professor Derrick White logged onto Twitter to articulate his stance in greater detail.

In a long thread, the Lexington native argued that Rupp purposefully kept Kentucky basketball segregated longer than was necessary.

White suggested that Rupp operated in “bad faith” by offering Unseld and Wallace scholarships without actually meeting with them and by failing to outline a plan to keep Beard safe on road trips in SEC play. White also asserted that Rupp’s policy of only pursuing potential African American impact players was actually a “racist double standard.”

“Rupp offered and signed numerous white players that sat on the end of the bench,” White wrote. “The only in-state Black players that Rupp offered between 1964-1969 were Mr. Basketball. The best player in the state of KY.

“Rupp had the power and support from the governor and the school president but held Black players to a standard that only a few met. They clearly saw that he wasn't going to support Black players. His racial stubborness, racial double standards, kept his team white. This is racism.”

To many of Rupp’s former players, those arguments miss the mark. They insist that Rupp was sincere in his recruitment of Unseld, Beard and Wallace and that his only recruiting agenda was finding players who could help him win.

Some of Rupp’s supporters wonder how differently he would be perceived today if Unseld or Beard had chosen Kentucky over Louisville. Or if all-white Duke had defeated Kentucky in the 1966 national semifinals and advanced to meet Texas-Western in the next night’s title game.

“If he was a racist because he didn't have any black players, then I guess every single coach in the SEC in those days must have been racist,” said former Kentucky guard Terry Mills, who played for Rupp from 1968-71. “This subject has been investigated with him several times and it never goes anywhere. I don’t think there was any terminology he used or any actions that he took that would lead you to believe he was a racist.”

So who really was Adolph Frederick Rupp? A racist who stood in the way of the integration of Kentucky basketball? A misunderstood figure who treated everyone equally? A pragmatist who could have done more to help African-Americans but simply cared more about winning than racial justice? Maybe the most even-handed perspective comes from a man who dared ask Rupp why he didn’t coach more Black players, a man who was recruited by Rupp but never got to play for him.

Warford, the second Black player and first Black graduate in Kentucky basketball history, arrived in Lexington months after Kentucky forced Rupp to retire at age 70, at the time the university’s maximum retirement age for all employees. Warford understands if others label Rupp a racist, but in his limited interactions he never saw enough firsthand evidence to feel that way.

“In my dealings with Rupp, he wasn’t what other people described him as,” Warford said. “I’ve had to fight things said about me that weren’t 100 percent factual or true and there’s nothing worse. I’d hate to have my enemy decide my legacy.”

More from Yahoo Sports: