Praying for It to End: Inside the Vatican’s Coronavirus Scare

First the priests began to disappear.

They used to flock to Benito Canizzaro’s restaurant, Krugh, on the lively Borgo Pio. There they would loosen their clerical collars for the day, and indulge in earthlier pleasures: food, conversation, perhaps a little wine. That was a different time—a whole week ago.

Now the Borgo Pio, which adjoins the Vatican, has seen scarcely a single frock. Even before the entire country was placed under total lockdown, their ranks were thinning. “I normally see many priests,” said Carizzano on Saturday, March 8. “Now there are no priests. Absolutely no priests around.”

“Maybe,” he went on, “they’re afraid to pick the virus up outside—and bring it inside.”

As with much of the world, panic had taken hold in the enclave. On Friday, March 6, the first case of COVID-19 was discovered inside the Vatican’s walls, having apparently spread from Lombardy, where the contagion is most widespread. The infected person, who has so far gone unnamed, was present at a large international conference on artificial intelligence in early March, which featured priests alongside high-profile tech executives, among them Microsoft CEO Brad Smith.

And so people like Canizzaro, who live and work at the Vatican’s fringes, began to notice that the city-state’s clergymen had disappeared from view. Some observers speculated that the vanished priests had returned abroad, fleeing the encroaching “red zone” up north, and that those with nowhere else to go had sealed themselves off inside the Vatican. The pope, meanwhile, had been cordoned off, amid speculation that he himself had contracted the virus—although the Vatican insisted his light sniffling was merely a cold, which was “running its course, without symptoms linked to other pathologies.”

Yet, now, a week later, fears persist: Occupying a mere 44 hectares in Rome’s northwest and home to only 605 full-time residents, the tiny city-state of the Vatican attracts hundreds of thousands of pilgrims in a normal week. There in St. Peter’s Square, and in the Sistine Chapel, and squeezed together in the gloom between the balustrades that line the winding stairs up to the Basilica’s vast dome, they revel, whoop, sweat, spit, litter, hold hands, exhale in wonder, making one another, and the city itself, vessels for contamination. For those who live in the Vatican permanently, many of them elderly cardinals and diplomats who are more susceptible to the virus, the risk is too great.

Some describe an air of oppressive claustrophobia taking hold as officials seek to stamp out the virus as it, conceivably, spreads silently within the city’s walls. Nuns have been discouraged from speaking with people outside the enclave, one told me. The smallest hint of an illness sparks terror. “There was a scare the other day,” recalled Sean Egan, an Irishman who sells tickets outside the main square. In the Vatican museum, he told me, a suspected COVID case sent security guards into a frenzy. “But it turned out to be a false alarm—it was just a baby, sneezing.”

Measures have been put in place internally. The Vatican’s healthcare clinic has eliminated all but the most urgent procedures to reduce the risk of internal person-to-person transmission, according to the Messaggero, a Roman daily. Papal offices in the second section of the Apostolic Palace, where senior ministers and functionaries work, along with nuns from abroad, are undergoing an extensive “sanificazione” which literally translates to “sanctification,” but in this context means something closer to “sanitization.” Functionaries have been asked to suspend all events in which healthcare professionals are involved, in order to “avoid the risks of COVID-19’s spread.” A planned sermon by priest Marko Rupnik, which was originally moved to a more spacious atrium in the Holy See in order to keep congregants from being too closely crammed together, was ultimately delivered in isolation, via livestream.

Now the Vatican is under total lockdown, along with the entirety of the country in which it is enclaved: invoking the spirit of wartime sacrifice, the Italian government has forbidden its people from leaving their homes unless for “essential purposes”; shops that don’t sell food, pharmaceuticals—or, naturally, tobacco—have been ordered to close; sports involving multiple people are off limits; tourists are advised to return to their hotels. St. Peter’s Square, too, is deserted.

Even well before the lockdown, Vatican authorities were working hard to stymie the daily influx of believers. While a downturn—now a total collapse—in tourism partly saw to that, the Vatican encouraged it further by, effectively, putting the city-state’s entire spiritual life on hold. Holy water was sluiced out of fonts held by large stone cherubs. A statue of St. Peter, at whose feet pilgrims typically worship, was cordoned off. Masses were cancelled, en masse. “Catechisms,” a milestone Catholic ritual, were postponed. Hand sanitizers were installed in clerical offices. The Roman Church, meanwhile—which is distinct from the Vatican yet deeply entwined with it—urged for all ceremonies, including masses, baptisms and burials, to be suspended, citing the growing “public health emergency.” The masses are still being held, says Chris Altieri, the Rome Bureau Chief for the Catholic Herald, but the faithful are not invited. The priests must deliver them unto nobody.

“The Church, ultimately, bowed” to the state, which had itself levied similar restrictions, said Andrea Riccardi, the founder of the Community of Sant’Egidio, a Catholic group with deep links to the Vatican. Although he acknowledged the Church did so reluctantly, he added: “It seems the Church can offer nothing for the moral stability of the Italian population as it faces this crisis.”

Meanwhile, church officials cannot totally quell the rumor, circulating most aggressively on Reddit, never a bastion of reliable reporting, that the pope, suddenly fallen ill in the worst of times possible, is sick with COVID-19 himself. Videos of Francis kissing the hands of revelers days before he first showed symptoms have done the rounds on the internet as evidence that he must have contracted the virus from a pilgrim, flown in from afar. The Vatican has denied this, and indeed the pope’s ailment appears to have subsided. (Asked for comment in person, a Vatican press officer pointed us to a more general online statement.)

Regardless, for the purpose of protecting the pope, he, too, has been sealed off. He has cancelled his appearance at the week-long spiritual retreat attended by clerical elders that every year marks the start of the Lenten season, and takes place in the Roman countryside. “Unfortunately a cold prevents me from participating this year,” Francis told Italian reporters. “I will be following the meditation from here.” Postponed too were affairs at the Apostolic Palace, in which the pope would have formally greeted visiting dignitaries and businessmen -- too risky. (The pope himself, for what it’s worth, doesn’t seem content with this arrangement either: earlier this week he provoked consternation by urging priests to visit Covid-19 sufferers in person.)

“It makes sense,” says Joshua McElwee, a Vatican expert and a writer for the National Catholic Reporter, a religious publication. Usually at the Vatican, there are “people pressed together, wanting to get close to the pope, wanting to get a photo,” he says. “The Vatican is trying to balance public safety with the need for spirituality.”

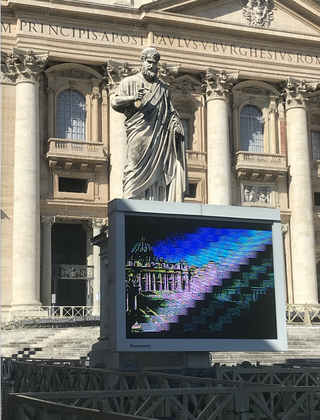

And on Sunday, most extraordinarily, the pope’s rendition of the “Angelus” sermon, a weekly tradition dating back over 60 years, was delivered to a square that was largely empty. The faithful, usually packing St Peter’s Square in their thousands, haunch to haunch, had been urged not to turn up. Why bother? Francis was not there either. Instead he was holed up in the library of the Apostolic Palace, from where he delivered his sermon by way of four large screens affixed to the great columns lining the square. The blessings were relayed on a loop, flickering with static, that was broadcast every few hours: the masses logged on and watched the feed via the Vatican website.

Francis began uneasily. “Good morning, a bit of a strange day with the pope encaged in his library…” he said.

After the spiel, however, there was one glimmer of hope. At the second window on the highest floor of the Apostolic Palace, from where the sermon is usually delivered, Francis himself appeared. For a few seconds, he waved to the few devoted gathered below. He then turned his back and retreated inside. He stood upright; he didn’t seem ill.

Julia Griraznova, a pilgrim who had travelled from Russia to see the pontiff speak, roared her approval. Francis may not have come down from isolation to mingle with the many, touching them and kissing their hands, as he had done just over a week ago. But his brief emergence was still, she said, “a miracle.”

You Might Also Like