Is it possible for pop stars with large egos to make a good film about their life?

These days it’s as though a pop star hasn’t existed unless their life has been immortalised on the silver screen. Freddie Mercury and Elton John have recently had the biopic treatment, in Bohemian Rhapsody and Rocketman respectively, and films about Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin and Bob Dylan are in the works. There are rumours of Bob Marley, Amy Winehouse and Celine Dion films, while The Who’s Roger Daltrey is planning a feature about Keith Moon and Big Little Lies director Jean-Marc Vallée has been linked to a film about John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

And now Madonna has announced she is co-writing and directing a movie about her life. The as-yet-untitled Universal Pictures film will be co-produced by Amy Pascal, whom the singer worked with on the 1992 baseball comedy A League of Their Own. No timescale has been given for the production, and Madonna will not act in it.

It doesn’t take a genius to see why the project appeals to her and to Universal. Biopics about music stars have been doing good business at the box office ever since 1954’s The Glenn Miller Story, starring James Stewart. In the Sixties, we had The Beatles’ semi-autobiographical comedy capers A Hard Day’s Night and Help!

But the template for the modern “star as a human being” biopic really took off following the back-to-back critical triumphs of 1978’s The Buddy Holly Story – for which actor Gary Busey received an Oscar nomination – and 1980 Loretta Lynn biopic Coal Miner’s Daughter, which earned Sissy Spacek an Academy Award.

Since then, music biopics have been the route to Academy Award success for, among others: Jamie Foxx, who won Best Actor for playing Ray Charles in 2005; Reese Witherspoon in 2006 for portraying June Carter Cash, the wife of Johnny Cash, in Walk the Line (2005); and Marion Cotillard who won Best Actress for her role as Édith Piaf in La Vie en Rose in 2008.

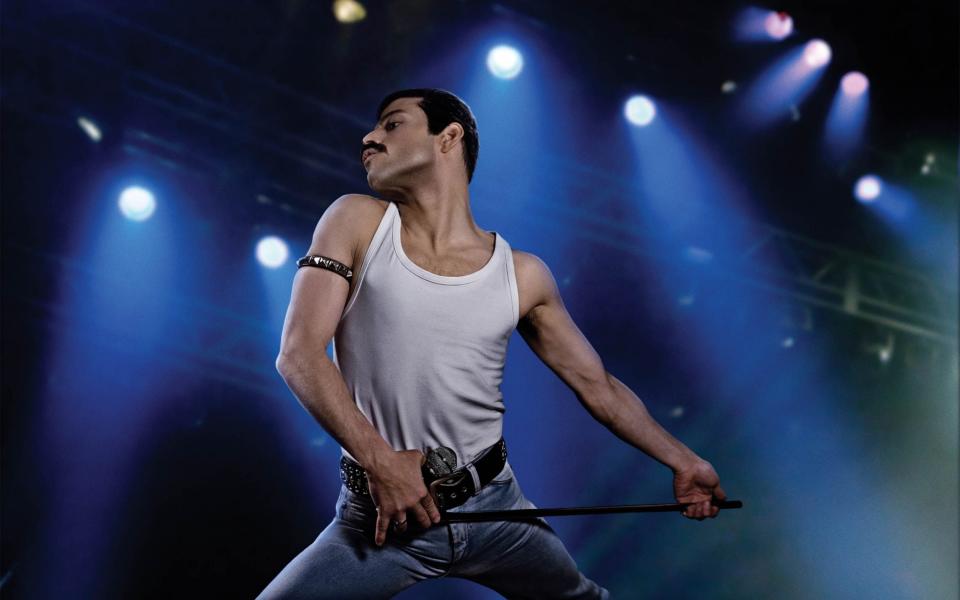

More recently, Rami Malek took home the Best Actor gong for his portrayal of Mercury, while Renée Zellweger won for Judy Garland at this year’s ceremony. It seems that actors, in an inversion of the famous football chant, only win when they’re singing. No wonder everyone wants a go.

The genre has myriad built-in attractions for producers. With a story arc that invariably goes obscurity-fame-crisis-redemption (or death), a musician’s life is tailor-made for the big screen. And the gap that almost always exists between a star’s public persona and their private life is a gift to screenwriters.

The potential to woo new generations of fans with a ready-made soundtrack will also have appealed to Madonna. Mötley Crüe, the scuzzy Eighties glam rockers, came out of retirement earlier this year to play concerts in stadiums across the US after the success of Netflix’s biopic The Dirt (only for Covid-19 to delay their plans, in a cruel extra twist to their redemption story).

Then there is the box office performance: biopics can win big here too. The genre accounted for just 0.6 per cent of films released in the UK in 2018 but took six per cent of the total box office, according to the BFI’s Statistical Yearbook. On so many levels, the genre appears risk-averse and bankable.

And yet as an art form, music biopics are always compromised by the issue of consent. A musician (or their estate if they’re dead) must grant permission for their music to be used, and no one is going to do so if a project paints them unflatteringly. Therefore, if consent is withheld, a project will gain realism at the expense of its one crucial ingredient. The unofficial 2013 Jimi Hendrix biopic, Jimi: All Is by My Side, contained no Hendrix music, an omission one critic politely described as “hobbling”. Conversely, artist-sanctioned biopics lean towards the hagiographic. “You can use my music but you have to tell the story my way,” is the gist of the deal.

This is where the Madonna project rings alarm bells. Announcing the film, she said it’s “essential” that she tells her “rollercoaster” life story with her own “voice and vision”. That’s fine in one sense. Madonna will be able to bring details to the screenplay that only she knows. Yet it will inevitably be a one-sided account. People’s character flaws are always as illuminating as their strengths, but a person’s natural inclination – especially a person as protective of her image as Madonna – is to omit those unedifying blemishes that actually make them who they are.

The project has a co-writer – Diablo Cody, herself an Oscar winner for the brilliant coming-of-age comedy Juno, and no wallflower. But the chances of Cody inserting anything into the film that the Queen of Pop doesn’t like – such as details about Madonna’s long rift with her brother, or the excoriating reviews she’s received over the years for her film roles (Swept Away, anyone?) – are non-existent.

The early years of Madonna’s career are the most interesting. Born into a middle-class Catholic family in Michigan in 1958, she studied the piano, learnt ballet, got good grades at school and then moved to New York in 1978, aged 20, where she went from a Dunkin’ Donuts waitress to a pop superstar in five years (with singles Holiday, Borderline and Lucky Star). Her impact on pop culture and fashion was immense. But it will need all the hard-bitten realism of Scorsese’s New York, New York it can muster to prevent it from being “Madonna does Flashdance”.

After that, the story – the official one, anyway – lacks a dramatic arc. Madonna has never suffered any cataclysmic fall from grace, a massive career downturn or, as far as I know, addiction issues. Madonna, famously, likes control. She has thrived for nearly four decades by reinventing herself (to varying degrees of success, but success nonetheless). Her life story is therefore not so much an arc as a series of waves. Which is great for longevity but less gripping for a 90-minute film.

And there are also Madonna’s chequered directing efforts to consider: 2008’s Filth and Wisdom and 2011’s W.E., which told the story of Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson. This newspaper’s review of the latter called it “stultifyingly vapid”. Let’s leave it there.

Of course, we must reserve judgment. And artistic merit and truthfulness are not essential for box office success. I didn’t like Bohemian Rhapsody: it was oversimplified, its chronology was wrong and it got nowhere close to showing just how tangled and dark Freddie Mercury’s life was. Also, the wigs. But at the end of the day, as Adam Lambert, Queen’s new frontman, put it to me last year, it “reminded [people] how good these f------ songs are”.

And guess what? Bohemian Rhapsody took almost $1 billion (£760 million) at the box office and hoovered up Golden Globes and Baftas as well as four Oscars. There’s no question that Madonna has a back catalogue to match Queen’s. So truth be damned. Perhaps the Material Girl will prove me wrong after all.