Pop’s mad king: my extraordinary day at Phil Spector’s castle

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

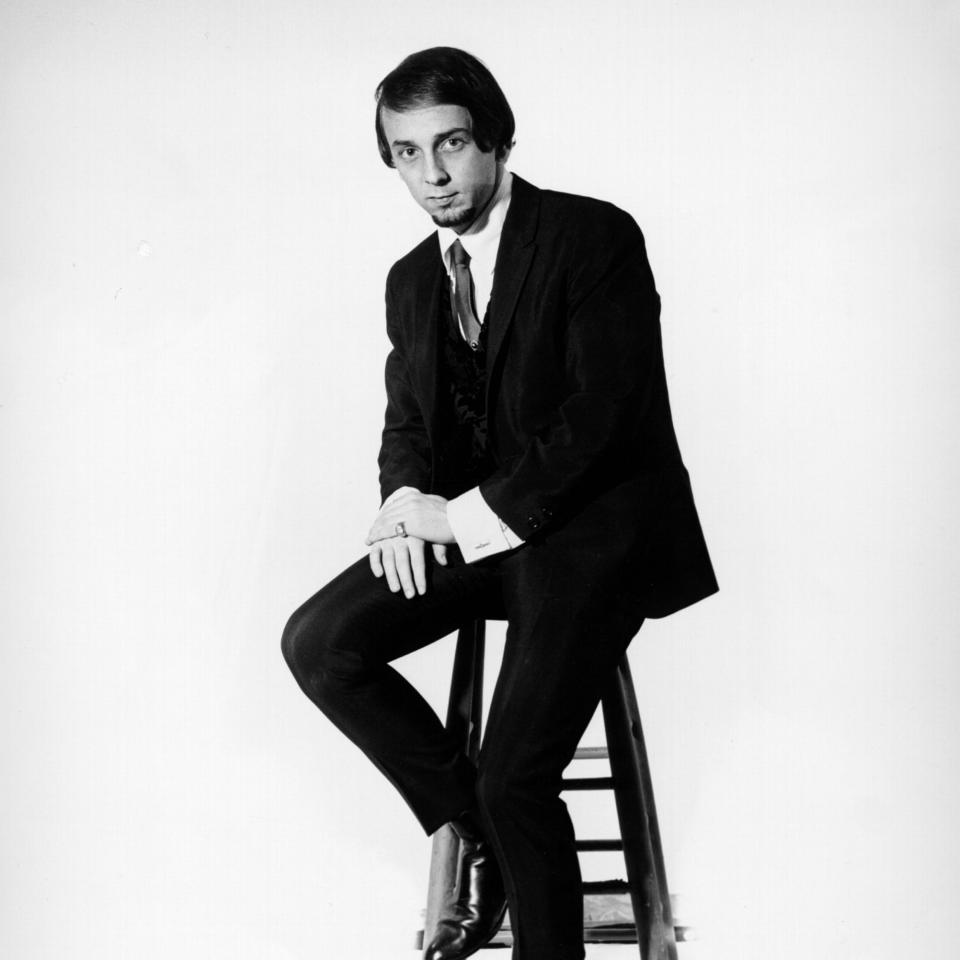

When I met Phil Spector in December 2002, I little imagined that a few weeks later he would become a murderer.

Spector’s years as the most important producer in pop music history, the architect of the Wall of Sound - were long behind him. All that remained were the stories - about guns and craziness, his need to control, the lawsuits brought by the artists he’d worked with, the way he’d kept his wife Ronnie, of the Ronettes, a prisoner in the home.

He had been living as a virtual recluse, and had not given an interview in more than 20 years, but after protracted discussions I had managed to secure a meeting. It would turn out to be one of the most surreal and extraordinary in my career,

I flew to Los Angeles and booked into a hotel on Sunset Strip, and was told to wait. Thirty-six hours later I received a call telling me a car had been sent by Spector to collect me; I walked out to find an impeccable white 1965 Rolls Royce driven by a liveried chauffeur.

The car keeling like a stately liner, we drove out of Hollywood down the freeway to the working-class suburb of Alhambra. The car ascended a hill and turned into the driveway of a huge Spanish style castle.

As Spector would later explain to me, he had always wanted to live in a castle - and this was the only one available.

The car stopped at a steep flight of steps. ‘Mr Spector likes people to walk up,’ the chauffeur said. I set off towards the top arriving at a solid oak door, where I was met by Spector’s assistant. Two suits of armour stood sentinel in the hall. I was shown into a sitting room and asked to wait. A piano, a gift from John Lennon, stood in one corner - the piano, he claimed, that Lennon had written Imagine on.

Classical music eddied softly around the room. At length Spector appeared, walking down the stairs, to the strains of Handel. He was wearing a shoulder length curled toupee, blue-tinted glasses, a black silk pajama suit with the monogram PS picked out in silver thread and three-inch Cuban heel boots. He looked bizarre, like a wizened child in fancy dress.

He perched on the sofa, sipping from a tumbler filled with something that might have been cranberry juice, might have been anything. Close up, his skin was sallow, like parchment. ‘I don’t like to talk,’ he said, but over the next four hours he talked like a man possessed - about his music, the Ronettes, the Crystals, the Righteous Brothers, the Beatles, about hustling and payola, success and failure.

‘I knew,’ he said. ‘People made fun of me, the little kid who was producing rock and roll records. But I knew. I would try to tell all of the groups, we’re doing something very important. Trust me. And it was very difficult because these people didn’t have that sense of destiny. They didn’t know they were producing art that would change the world.’

But that was then. For years, he said, he had not been well. ‘I was crippled inside. Emotionally. Insane is a hard word, but it’s manic depressive, bipolar.’ His parents had been first cousins, he said. Maybe that was something to do with it...He took medication for schizophrenia. ‘But I wouldn’t say I’m schizophrenic. I have devils inside that fight me. And I’m my own worst enemy.’

Our conversation was interrupted by a whirring noise, like a cuckoo clock and a voice chirruping the hour. ‘It’s two o’clock’. His wristwatch.

‘Timing,’ he said, ‘is the key to everything.

‘Okay’, he jabbed a finger at me. ‘You ask me. “What’s your name?’ And then you ask me, ‘What do you do for a living, and what’s the most important part of what you do for a living?’ Go ahead! Just for the conversation.’

Okay. What’s your name?

‘Phil Spector.’

And what do you do for a living?

‘I’m a record producer.’

And what’s the most important -

‘Timing…’ And he broke up in laughter.

He needed time out, he said, and left the room. I assumed to take his medication.

He returned an hour later. For years, he said, he couldn't face being with people, and he couldn’t face being with himself. He suffered from chronic insomnia, night after night, going crazy. Always ‘terrified’ of drugs, he began taking medication to moderate his moods and help him sleep. He had ‘waged war’ with himself, over months and years. Now, he said, he was trying to make his life ‘reasonable’.

His wristwatch spoke. ‘It's six o’clock.’

Six weeks after our meeting my interview with Spector appeared on the front cover of the Telegraph magazine. The headline was ‘Found: Pop’s Lost Genius’. I had promised Spector that I would send copies of the magazine, and had Fed-Exed early copies to arrive at his home on the day of publication - Saturday.

On Monday I was in the magazine office when someone came in from the newsroom, asking ‘What did you write to upset Phil Spector?”. We turned on the television. It was 10am California time. Filmed from a news helicopter, the castle looked like a gothic film set, cut to shots of yellow tape, police cars, detectives moving purposefully around the grounds. An unidentified woman had been found shot dead in Spector’s home.

For a terrible moment, a scene flashed across my mind. Spector had read my piece, disliked it intensely, and in his fragile state of mind - ‘I have not been well’ - taken revenge on his assistant. (I would later discover the magazines would arrive late. He had not read the article.)

It was some hours before it was revealed that the victim was actress Lana Clarkson, whom Spector had met in the early hours of Monday morning at a nightclub, the House of Blues, where Clarkson was working as the VIP greeter, and persuaded to come home with him. In the subsequent murder trial, the chauffeur who had taken Spector and Clarkson home - the same chauffeur who had ferried me to the castle a few weeks earlier - testified that as she climbed into the car she had leaned across and told him, ‘it’s just for one drink.. I won’t be long.’ Spector told her. ‘You don’t talk to the driver.’

The killing left me shocked. I had liked Spector when I met him; he was hospitable, funny, candid. He had given me one of the most extraordinary interviews I’d ever had. Within 24 hours of his arrest it was being quoted in newspapers all over the world.

At that point, the circumstances of Lana Clarkson’s death were unclear. He claimed she had killed herself. I wrote to him expressing sympathy for the predicament he now found himself in, but heard nothing back. Nor did he reply later when I wrote to inform him that I intended to write a book about his life and career and request another interview.

It would be almost five years before I would see Phil Spector again. This time he was sitting in courtroom no 106 of the Clara Shortridge Folz Criminal Justice Centre in Los Angeles, on trial for murder. (Bizarrely, the first business of the trial was deciding whether I could attend. I had been interviewed by the LAPD about my meeting with Spector, and placed on a witness list by the prosecution. The defence objected to my reporting from the courtroom. The judge ruled that I was able to attend, and I was not called as a witness.)

Spector looked almost unrecognizable from the man I had met previously. He was dressed in a beige 3-piece suit; his surgically tightened face was pale and wan. He wore a new hairpiece - a blonde, pudding-bowl number that made him look like Brian Jones, or Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music. His hands trembled violently and fear clouded his eyes. He looked like a small boy who’d set off a firework and discovered he’d burned down a house.

It was a demeanour he would maintain throughout the trial. It was as if all this was happening to somebody else. On one occasion, during an adjournment, he passed by me and caught my eye. If he recognised me, he didn’t show it. Later, I caught sight of him at the end of the corridor, conferring with his wife Rachelle (whom he had married while he was awaiting trial). She was pointing me out. He looked and turned away.

Throughout the trial, the defence tried to turn the tables and make it seem as if Spector was the victim and it was Lana Clarkson who should be on trial. She was depicted as a washed-up actress who had gone home with Spector to further her career. She was a depressive, they said, suicidal. It was ‘accidental suicide’, she had ‘kissed the gun’.

The prosecution provided quite another picture of Lana. In their summing up they employed a device that would not be allowed in an English court: a screen was put up and a film was shown - a collage of photos and clips showing her as a vibrant, positive, happy, smiling woman, all the things her friends had told me she was, while her favourite song - Peg, by Steely Dan - was played. At the end there was only one dry eye in the courtroom: Spector had averted his gaze, his expression stony-faced.

I had no doubt that he was guilty. But, incredibly, there was a hung jury. It took a second trial to convict him of murder.

What I had come to realise in interviewing Spector, and later in writing the book, was that the broad brush picture of him as imperious, controlling, rock’s gun-toting mad man was in part true, but, of course he was much more complicated than that. His father had killed himself when Spector was nine; he had lost a 10-year-old son to leukaemia.

He was a man who believed in his genius, but at the same time was riddled with insecurities, who was mentally ill. The world of rock and roll had indulged behaviour that in any other sphere would have begged for some kind of intervention. Phil loves his guns! How wild is that! But nobody had taken them away from him. Lana Clarkson would still be alive today if they had.

His life embodied the eternal contradiction: a man who brought happiness to millions, but seldom knew happiness himself, and who in an arbitrary moment of madness had taken Lana Clarkson’s life.

‘Listen’, he said, when we met. ‘People tell me they idolise me, want to be like me, but I tell them, “Trust me, you don’t want my life”, because it hasn’t been a very pleasant life. I’ve been a very tortured soul. I have not been at peace with myself. I have not been happy.’

A troubled genius and a murderer. It’s possible to be both.