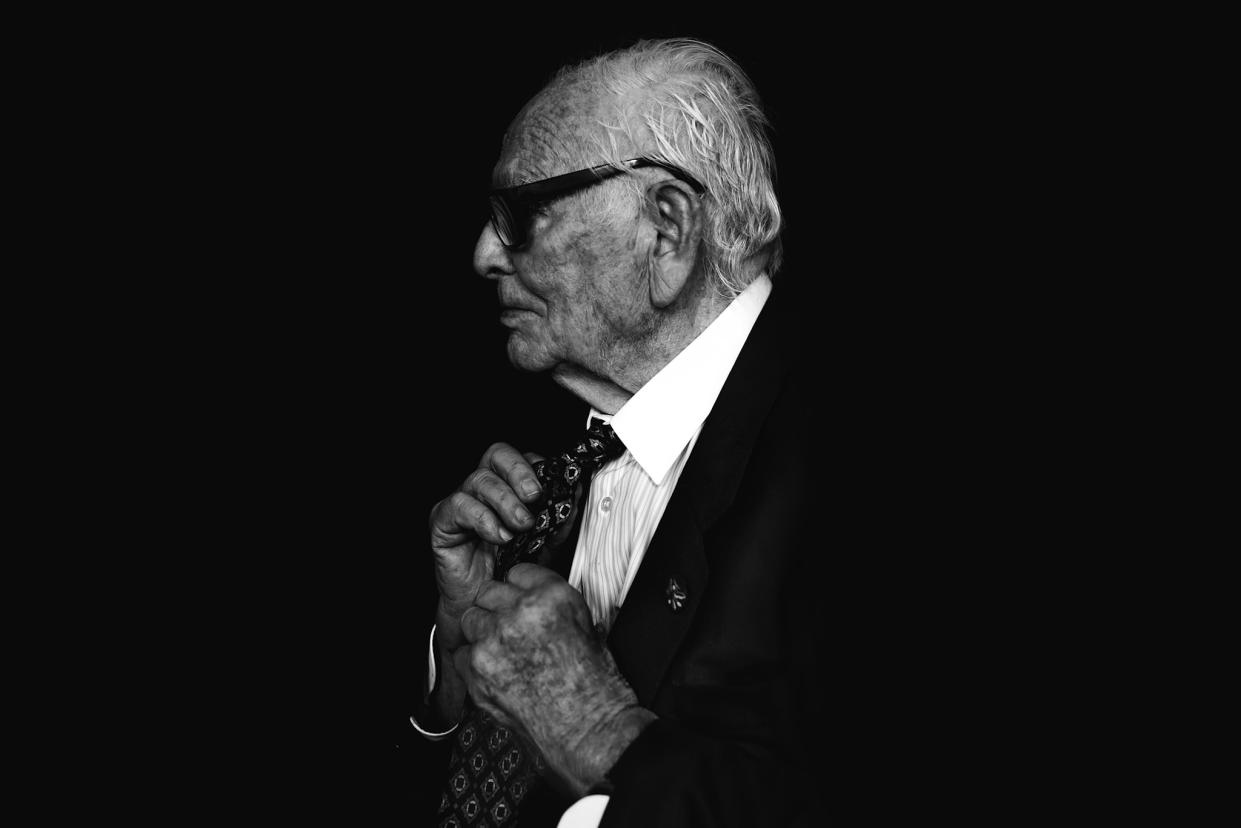

Pierre Cardin Dies at 98

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

PARIS — The fashion world on Tuesday paid tribute to Pierre Cardin as a pioneer who marked fashion design with his futuristic clothes in geometric shapes and revolutionized the industry by launching ready-to-wear and creating the licensing model that made him one of France’s richest men.

Cardin died Tuesday in a Paris hospital at age 98 due to old age, according to his longtime spokesman Jean-Pascal Hesse. The Space Age couturier, who dressed everyone from Jackie Kennedy to Jeanne Moreau, last appeared in public in September at a celebration of the 70th anniversary of his label.

More from WWD

Among his roughly 50 surviving relatives is his great-nephew Rodrigo Basilicati Cardin, who will take over the business, which includes the Paris restaurant Maxim’s, according to a statement issued by Cardin’s family.

“Today, we all aspire to the continuity of the creative work of our uncle under the leadership of Rodrigo Basilicati Cardin. With the loyal support of the house staff, he will take over, lead new projects while respecting the fashion heritage left by his talented predecessor,” Cardin’s nephews and nieces said.

They paid tribute to Cardin’s “unique artistic legacy in fashion, but not only.” The designer’s endeavors stretched from clothes to cars, architecture and theater. He put his name on everything from cigarette lighters to orthopedic mattresses, and staged catwalk displays in spectacular settings, such as the Gobi desert or his bubble-shaped Palais Bulles on the French Riviera.

“We are all proud of his tenacious ambition and the daring he has shown throughout his life,” the family said. “Always driven by a desire for openness, he has succeeded in making his name and brand known and established throughout the world.”

Basilicati Cardin, who took on the Cardin name in April 2019, said he planned to continue running the business as before. “I think I have absorbed the principles of freedom that he held so dear. He wanted things to continue as they are. I won’t change anything in terms of the structure of the company,” he told WWD.

“We will continue his work and project ourselves into the future, as he always did,” said Basilicati Cardin, who worked alongside his great-uncle for close to three decades. “I expect the whole family to support me.”

The Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode called Cardin a “precursor” who marked fashion history with his innovative designs. “Combining inventiveness, business and communication skills, Pierre Cardin captured all his long life the zeitgeist, its opportunities and all its revolutions,” Ralph Toledano, president of the federation, said in a statement.

“He was a visionary. He founded his house in 1950 and launched a ready-to-wear collection in 1959. Twenty years later, others were claiming they invented ready-to-wear, but he did it in 1959 in partnership with the Printemps department store,” Toledano told WWD.

“He was the first to go around the world. He went to Russia, China and India before anyone else even thought about it, and he invented the licensing model that later allowed all the major couture houses to grow,” Toledano added. “They all walked in Pierre Cardin’s footsteps.”

Cardin claimed the Chambre Syndicale, French fashion’s governing body, expelled him for showing rtw, but Toledano said the story was apocryphal. “It’s false. It caused a scandal,” he said, adding that the industry organization nonetheless held Cardin in the highest regard.

Bernard Arnault, chairman and chief executive officer of LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, noted that Cardin was instrumental to the founding of the House of Christian Dior, one of the flagship brands in the luxury conglomerate’s sprawling empire. Even in his old age, Cardin frequently attended Dior’s runway shows.

“Pierre Cardin was the last designer of the miraculous generation that blossomed immediately after the war. I salute a man of immense talent, who managed to build a magnificent dialogue between Italy and France and who, always, tried to outline a daring future through a futuristic and inspired aesthetic,” Arnault said in a statement.

“He himself reminded me, not so long ago, that he was alongside Christian Dior on the first day of the maison’s opening, and that he had been his first tailor for the first four years. What an extraordinary life!” he concluded.

In a separate statement, Dior paid tribute to Cardin’s “singular personality and his essential role in the history of French fashion.” It noted Cardin was just 24 when he was named head of the tailoring atelier at the newly founded house.

“From 1947 to 1948, Pierre Cardin produced suiting for Dior collections, shaping the Corolle coats and structuring the En Huit silhouettes of the revolutionary New Look. Driven by this new effervescence and by a unique creative energy, the couturier founded his own house after three years working alongside Christian Dior, who encouraged his initiative,” Dior said.

“With a profoundly futuristic vision and a pioneering spirit, Mr. Cardin reinvented haute couture and ready-to-wear with virtuosity. An aesthete who shared Monsieur Dior’s fascination for the arts, he drew inspiration from theater, painting, design and architecture to nourish his one-of-a-kind universe, a true symbol of excellence in fashion,” the house added.

François-Henri Pinault, chairman and ceo of Kering, also paid tribute to Cardin. “With the passing of Pierre Cardin, we have not only lost a visionary designer, but also a revolutionary entrepreneur.

“The inventor of a modern form of fashion for women and men that was in complete harmony with its time, he conquered the world and established his name by his sheer inventiveness and determination. As someone who could think beyond geographical, artistic and cultural borders, he is among those to whom we are indebted for the global reputation enjoyed by French creation,” he said in a statement.

Giorgio Armani and Valentino Garavani both remembered Cardin as a congenial colleague. “I’m very sad to hear of the passing of Pierre Cardin. His Italian origins have always made me very proud of his achievements,” Armani said.

“Cardin was a true innovator: for the shapes he devised, but also for his unique approach to business. From perfumes to restaurants, he is the inventor of brand diversification: a veritable genius and a gentleman. And very supportive, too. When I met him, early in my career, he told me I would go far. I will never forget his words of encouragement,” he added.

“He was not just a designer, he has been a true innovator. I have a memory of an event in Mexico in the Seventies where we did a runway show together — I was representing Italy, he France,” Garavani recalled. “He was always polite and never competitive or moody. He was such a gentleman. He will always be remembered as the biggest futurist in fashion.”

Proud to be the last post-war couturier still heading his own label, Cardin never officially named a successor, although his entire design team, including protégé Pierre Courtial, took a bow after the September show, which included a display of his most recent designs.

Fashion industry figures including Jean Paul Gaultier, Christian Louboutin, Inès de la Fressange and Michèle Lamy attended the event held at the Théâtre du Chatelet, which included a screening of the documentary “House of Cardin.”

“I made my first steps into the world of haute couture on my 18th birthday — the day I met Pierre Cardin and joined his team. He was a mentor to me,” Gaultier said. “He was a multitalented mastermind: a couturier, head of an atelier, a designer, a manager, a businessman, a show producer, an ambassador for France, a philanthropist — so many roles he managed to succeed in throughout his life. He was an emperor, a conqueror who forever left his mark on the fashion industry.”

Rick Owens recalled a chance meeting at the cafe next to his house in Place du Palais Bourbon in Paris.

“Mr. Cardin came over to my table and introduced himself to me. I think it was the most glamorous night of my life,” Owens said. “I would see him there periodically for years and years and we would always say hello, briefly and formally, but warmly.”

De la Fressange recalled working for Cardin when she was young on a show where models weren’t assigned their own looks to wear, as is tradition. “Each time we came back from the runway, we would pick up any clothes. He would say: ‘If something is good, it fits everyone.’

“I was just laughing with the other girls, saying that if you have a foot size 39, it’s not the same as if you have a foot size 42,” she recalled. “But after years and years, I realized that he was right, that when you really like something, it fits and you don’t care anymore — even about the size.”

For another couture collection, Cardin hadn’t given models blouses to wear under their jackets. He told them to go to the Cardin men’s shop around the corner to pick up one there. So he was pairing men’s cotton shirts with couture jackets.

“I thought: ‘He’s crazy, this one,’” admitted de la Fressange. “But finally, no — clothes are made to be mixed up. The important thing is the general style. And in this case, he was right, too. That was a very modern thing to do, and very chic and elegant.”

Proof of his continued influence on young fashion designers, Simon Porte Jacquemus often cited Cardin as a role model. “It’s a very sad day for fashion,” Jacquemus said on Tuesday. The designer said he was fortunate enough to be interviewed alongside Cardin last summer, calling it an “exceptional” meeting.

“Pierre Cardin was an iconic couturier, who made me love fashion from an early age. I’ve always been fascinated by his lifestyle and by the futuristic way he projected his brand beyond clothing. I admire his independence, his freedom and his career. His colors, shapes, aesthetics and way of seeing the future will always remain a source of inspiration,” he continued.

Alexis Mabille said he had the opportunity to show some of his early designs in Cardin’s Palais Bulles during the Cannes Film Festival in 2008. “It was so fun and exhilarating to showcase the models in the bubble-shaped walkways of this whimsical house,” he said.

“Mr. Cardin had always been out of time, he is an avant-gardist and wanted to create his vision of fashion, jewelry and design. His idea of volume was so visionary, and he did it with such a sense of humor,” Mabille said. “I think Mr. Cardin has inspired us all. We have lost one hell of a man.”

Georgina Brandolini was working with Valentino when she accompanied a host of top European designers on a 1993 trip to China for its first international fashion fair — and Cardin stole the show. “He was a huge star,” she recalled. “When he walked out of the hotel, there was a crowd of people waiting for him. He was huge not only in fashion.”

Indeed, Cardin was the hands-down expert on producing and selling designer products in China, having started doing business there in 1976 and having built up a clothing production, distribution and food empire that had become a household name.

Brandolini also recalled how attached the designer was to his brands. Years ago, an American friend of hers was interested in acquiring Maxim’s and asked her to convey his interest to Cardin. “He said, ‘Darling, I will never sell Maxim’s, I love it so much,'” she recalled. “He was someone very, very nice — and full of charm.”

Shoe designer Manolo Blahnik said: “Pierre Cardin was a true pioneer of modern, futuristic clothing. He was very influential with a modern sense of 20th-century fashion. I was a great admirer of his vision.”

Rosita Missoni mourned the loss of a peer. “Since I’m turning 90 next year, I belong to the same generation as Pierre Cardin. Actually, back in the days, Ottavio and I got a phone call from his office because he wanted to see us. We did go to Paris and once there we found out that the deal he wanted to propose was not really working for us,” she said.

“After that, we saw Pierre on many occasions, also at Rinascente where he was selling a collection he was doing for them. We spent together so many nights in Paris talking about so many things, including fashion. Pierre has been the one who has really modernized fashion, translating his high-couture ideas into more affordable ready-to-wear pieces. He can really be considered one of the fathers of the ready-to-wear as we know it,” Missoni added.

“It is with great sadness that we learn today of the passing of Monsieur Pierre Cardin, a great master, innovator and forerunner of the future in fashion and design,” said Angelo Trocchia, ceo of Safilo Group, the eyewear manufacturer which has been the Cardin licensee since 1991.

“In almost 30 years of collaboration with Safilo, we have created with him and his maison eyewear collections that celebrate the visionary and avant-garde creations of Monsieur Pierre Cardin’s universe: real design objects that will stand the test of time. A unique designer, he will always be a point of reference for all of us,” he added.

“House of Cardin” filmmakers P. David Ebersole and Todd Hughes, based in California, received news of Cardin’s passing from the family early Tuesday morning. The couple last saw Cardin in September during the 70th anniversary celebration.

“When no one else was traveling, Pierre Cardin called up the Ministry of Culture in France and said, ‘I need my filmmakers here for this event,’ and we were allowed to travel. So we held his hand, we looked into his eyes and told him we loved him, and got to have our final moments with him,” Ebersole said. “We thought it was our most recent moment and then we’d see him when he turned 100.”

“Meeting him in our mid-50s, he really opened our eyes to the fact that our lives had just begun. Anything is possible,” Hughes said. “And he showed us by example: do what you love, and the rest will follow. I’ve heard that my whole life and I’d never seen it actualized, and this movie was that.”

“I think that we went into it thinking that we were doing something about our design hero, and in many ways he’s become our life hero,” Ebersole added. “He is an inspiration, and he really teaches you that life is for living and making and doing.”

Cardin was born on July 2, 1922, in San Biagio di Callalta near Treviso, Italy, and was apprenticed to a tailor in Vichy, France, when he was just 14. During the Second World War, Cardin worked for the Red Cross, and after the war, he did stints at Paquin and Schiaparelli, then became the head of Dior’s tailoring atelier in 1947, where he worked on the iconic Bar jacket, a pivotal piece of the New Look.

He was one of the first seven employees to work at Dior; within three years, the company employed 800. He made the costumes for Jean Cocteau’s 1946 classic “Beauty and the Beast,” and later said he had been given an opportunity to become the artistic director of Chanel in 1950 but turned it down in order to open his own house.

In 1951, Cardin created about 30 costumes for Carlos de Beistegui’s celebrated 18th-century Venetian fete-themed costume ball at the Palazzo Labia. He dressed Salvador and Gala Dalí, Dior himself, Marie-Louise Bousquet and decorator Victor Grandpierre, concealing them under tall, tricorne-wearing dummies sporting satin masks with jeweled eyes and black lace. The event put him on the map.

During the Sixties, Cardin became known for his Space Age designs, which reflected a longstanding fascination with geometric forms, particularly the bubble; the Bubble Dress was one of his most famous designs. He and Andre Courrèges were in the vanguard of these sorts of looks. His influential designs included little shift dresses in orange, mauve and green with embossed designs, worn with PVC bonnets, gloves and thigh-high boots; color-blocked dresses, sometimes with a target motif; dresses with cutouts and stiff belts, and kimono-style dresses with stylized geometric sleeves. At the time, WWD called him “one of the few original spirits designing great clothes in Paris today.”

He recalled his early days decades later by saying that, as a young tailor, he developed the practice of “dreaming about something, then carrying out the dream. I never wanted to start something I couldn’t finish. If I didn’t think I could finish something, I tried not to think about it at all. It took 30 years to build a name.

“My first year of establishing my own designs was difficult because I was thought of as radical. But I never wanted to get ideas from movies or from some past decade or from the streets.

“I was a young wolf,” he said about an early trip to the U.S. “I was 25. I was this crazy young couturier.”

Very soon, though, he observed that his interest in fashion was waning. In 1966, he said, “After 20 years, do you really still think it interests me to dress a woman?” However, he also said, “Jeans have killed fashion. The street doesn’t create. We couturiers must create if fashion is ever to come back to the street.”

When he talked about his temperament, he made it clear that he was a loner. WWD described it by saying, “He possesses a sort of tunnel vision that places him curiously somewhere between Sartre’s man of action and Ayn Rand’s capitalist superhero.”

“I like being alone,” he told WWD. “I don’t like the crowd. It’s useless to show one’s difficulties. I can’t say I have any, but even if I did, I wouldn’t let them show. If I don’t succeed, it’s my fault. The difficulty is never with other people, it’s with oneself.”

In July 1973, he assessed other designers, saying he admired “only Balenciaga, Schiaparelli, Christian Dior and Courrèges. Each had his or her authenticity. Balenciaga was a great creator. Schiaparelli gave women a chic that was characteristic of pure modernity for her time. Courrèges really created a coup in fashion when he first became independent. And Mr. Dior was always following his own path. As far as I’m concerned, Chanel never influenced fashion one bit….One suit in her entire career is not sufficient.”

It was his licensing empire that was truly extraordinary. Cardin was the first designer to do extensive licensing, and the number of his deals in this area became and continued to be remarkable, a total of 800 to 900 in 120 countries. As WWD put it in April 2008, these are “what some consider to be a garish number of licensees that even includes food products.”

“I have a name. I have to take advantage of it. No one in the world has so many licenses,” Cardin said in the same article. “Women’s, children’s, men’s, glasses, forks, tables, chairs, lamps, curtains, watches, ties.”

“I don’t have to meet people socially,” he once regally said to WWD. “I eat on my own plates. I drink out of my glasses. I wash with my own soap. I wear my own perfume. I go to bed in my own sheets. I have my own food products. I can sit in my own armchair. I live on me. That is very rare. I am probably the only man in the world who can say that.”

WWD, and its then-sister publication Daily News Record, covered his career in both women’s and men’s fashion throughout his long life. He told WWD in May 1967, “As I have long predicted, the haute couture will become a laboratory for ideas….Today I have as clients the 10 most talked-about women in Paris….The Baronne Guy de Rothschild orders 30 models in a season, but what is that?

“The only way to make money is with ready-to-wear. You have no idea how I was criticized by my couture colleagues when I started a department at the Magasins du Printemps.”

During the design heyday of his fashion house in the Sixties, he dressed such top stars as Vanessa Redgrave; Moreau wore his clothes exclusively, and she and the designer had a romance. WWD photographed them together frequently. In 1965, Nicole Alphand, wife of Hervé Alphand, the former French ambassador to the U.S., went to work for Cardin as a p.r. woman and brand ambassador, liaising with VIP customers like Jackie Kennedy.

Andre Oliver was Cardin’s top assistant for 40 years. He helped design Cardin’s highly influential men’s collections of the early Sixties, which were based on an Edwardian look and were made popular by The Beatles. In the early Eighties, Cardin and p.r. veteran Bobby Zarem backed Oliver in his own business, a men’s store under his own name, which thrived for a time. Cardin had intended Oliver to be his heir; unfortunately, Oliver died in 1993.

In recent years, Cardin had been shopping around his empire, including Maxim’s. Everything sold together, he stipulated, would go for north of $1.3 billion. But after offers from the likes of the Sultan of Brunei were rejected, those in the know came to the conclusion that he didn’t want to sell his business after all. He continued to insist on handling everything in his company himself, including signing every check.

Cardin also created a dizzying array of other products, including wigs for men, which he launched in 1970, at a time when women’s wigs were a big business. In 1972, he designed cars for American Motors, creating a series of Javelin muscle cars in vivid stripes. He also expanded into restaurants, buying Maxim’s restaurants in 1981 and creating branches in New York, London and Beijing, along with Maxim’s sandwich bars in boats on the Seine. Later, Maxim’s hotels and food products were added to this lineup.

Cardin’s properties included the ruins of the Marquis de Sade’s chateau and 14 other town houses in Lacoste, France; the Palais Bulles, in Cannes, designed by architect Antti Lovag; the Ca’ Bragadin in Venice, which he liked to say had belonged to Casanova, but which had really belonged to Giovanni Bragadin di San Cassian, Bishop of Verona and patriarch of Venice. He also had the Espace Cardin, a former theater that he used for his fashion shows and as an arts space that helped launch the careers of actor Gérard Depardieu and director Robert Wilson; it closed in 2016.

Although Cardin eventually dropped plans for a futuristic skyscraper near Venice in the face of public and political opposition, he continued to work on new projects, including a cultural center in Houdan, 40 miles west of Paris, that includes individual houses that will be used for artists’ residencies, and a 500-seat theater. It is scheduled to open next year.

Last summer, his annual festival at the Château de Lacoste was one of the only cultural events to go ahead despite the coronavirus pandemic, with performances by choreographer Marie-Claude Pietragalla and Italian tenor Andrea Bocelli. Cardin also launched a film festival in Lacoste with open-air screenings of musicals including “West Side Story,” “La La Land” and “Hair,” and continued to produce plays and musicals in Paris and elsewhere, despite dwindling audiences.

In 2008, he opened a furniture shop on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. “My furniture used to be considered provocative,” he said. “But now people like it and say that I’m a very important designer.” In 2018, Sotheby’s Paris branch held an exhibition of Cardin’s furniture designs from the Seventies.

He enjoyed throwing elaborate fashion shows in venues as far-flung as Beijing and the Gobi desert. In 1980, he had a retrospective fashion show at New York’s Metropolitan Museum, followed by a black-tie dinner. Describing what would be shown, WWD quoted him as saying, “’There will be short things, long things, sculptural things, flowing things.’”

The paper went on to add, “There will also be hats that look like puffed meringue pastries from 1952; strict little Empire-line chemises from 1954; huge car radiator-like collars from 1956; draped, drooped and deflated-looking blouson jackets from 1958; prophetic black-and-white striped mink coats from 1963; ostrich feather fantasies from 1964; cookie-colored oversize graphics on minidresses from 1965; heavy plaid minicoats with matching gaiters from 1965; Sputnik-like mini dresses with hats that look like upside-down refuse receptacles from 1966; circus tent coats from 1967; plastic thigh-high Barbarella boots from 1968; maxicoats over microminis, from 1969; hats that look like inverted flowerpots with TV-shaped holes for the eyes and nose,” and so on.

One of Cardin’s more unexpected ventures was appearing opposite Moreau in the 1975 film “Joanna Francesca.” In 1992, he was named a member of the Immortals of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, part of the prestigious Institut de France, the first couturier to be so honored. In 2010, he received the Fashion Group International Board of Directors’ Legend Award.

At the time he said, “My aim is to boost sales and to raise my profile among young people. Since I don’t get a lot of press coverage, young people don’t know who I am. I want to show them I am still avant-garde and that I produce original designs and that I also want to help my licensees, who depend on my creativity, after all.”

Asked if he thought he should bring in a young designer to “revitalize” his business, he responded, “I have five people who are sketching for me who are very young. And I think that the young designers today are less avant-garde than I am. I’m still in good shape. I still go to work every day.”

Armand Hadida, who owned the L’Eclaireur group of concept stores, featured Cardin’s designs, saying, “There is nothing commercial about my approach. Pierre Cardin has so much to say. He is like a fashion bible — he’s completely impervious to age.”

Andrew Burnstine, former executive vice president of the upscale retailer Martha’s, recalled how Martha Phillips, the store’s proprietor and his grandmother, first purchased Cardin’s collection in the late Sixties for her Palm Beach, Park Avenue and Bal Harbour locations. “She knew that these were the styles and silhouettes that her fashion conscious customers would like. She bought a few pieces that she wore herself, and which would always result in her best customers wanting to buy what she was wearing. Martha referred to this concept as what we now know of as ‘buying the clothes off my back,’” Burnstine said.

Phillips was such a supporter of Cardin’s licensing prowess that she bought the signature 1980 Lincoln Town car in beige on beige that the designer collaborated on.

Burnstine said, “She thought these were colors that the designer would certainly have approved of, and fondly referred to the car as ‘fashion on wheels.’”

In 1990, he brought a Russian rock musical, “Junon and Avos: The Hope” by Alexey Rybnikov, to New York and threw a party for it at Maxim’s in the city. He estimated that he had invested $1 million in the production. That year, there was also an exhibition, “Pierre Cardin: Past, Present and Future” at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. More recently, the Brooklyn Museum staged a retrospective titled “Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion,” while the Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf held a show called “Pierre Cardin. Fashion Futurist.”

Matthew Yokobosky, who curated the Brooklyn Museum exhibition, recalled his first meeting with Cardin about the retrospective. Yokobosky said, “We were posing for a photo and I reached over to close the top button on his shirt and adjust his tie. Just as I was about to do it, he said, ‘You should unbutton your shirt.’ Then we were the same, but in a different way than I imagined. At that moment, I really understood why Pierre was a maverick. He could break rules or expectations, in a gentle and unassuming manner, with a suggestion, and you would participate easily. That is how he created fashion revolutions.”

Olivier Gabet, director of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, said Cardin brought a new energy to French haute couture — but that’s not all. “History has spent too much time debating whether Cardin, Courrèges, Paco Rabanne — not to mention Yves Saint Laurent — had been the first to come up with this or that. Above all else, these pioneers bore witness to a total revolution in fashion,” he said.

“Although it would be tempting to reduce Cardin to a form of futurism, to do so would be very simplistic and wrong. As a lover of Art Nouveau, he was the one who brought the mythic Maxim’s back to life. He delighted in the organic and the floral,” Gabet added.

“With vision and intelligence, he cultivated the fin de siècle idea of the total work of art — the Gesamtkunstwerk so dear to Wagner and avant-garde artists — art that encompassed everything, from fashion to accessories, from urban planning to architecture, from design to object,” Gabet said. “Everything fascinated him in equal measure, and his desire to overturn the hierarchies of art marked his era. Hence the power and presence of his legacy in the contemporary scene, from Pierre Yovanovitch to Simon Porte Jacquemus.”

Paula Wallace, president of the Savannah College of Art and Design, described Cardin’s ties to the school and its outposts. “A denizen of global fashion, Pierre Cardin adopted the Provençal village of Lacoste, as his second home almost 20 years ago, around the same time that SCAD Lacoste was born. He was exceptionally kind and attentive to our students, offering them advice and encouragement. He was our friend. Both Cardin and SCAD have poured our love and expertise into the tiny remote village, with Cardin hosting hundreds of performances in his grand open-air amphitheater under the stars and SCAD teaching thousands of graduate and undergraduate students in 40 restored medieval buildings. The world knows Cardin as a renowned fashion designer. The Luberon valley knows him as an architectural connoisseur and theater impresario. SCAD knows him as a neighbor and friend.”

The designer also had his own museum, which opened to the public in 2006. Recalling his early career, he told WWD, “I was inspired by satellites, by lasers, by the moon. I looked into the future. I was never inspired by a woman’s body. My dresses are like sculptures. I molded them and then I put a woman into it. It was more like architecture or art.

“As I look over all these dresses, I see a continuity of personality. It’s all Cardin. It’s all sculpture. It’s art.” Looking at a Seventies black dress with a metal necklace, he said, “I loved this idea of a dress with metal in it, like a necklace holding up the fabric. But nobody would make it. I found a man who made cars to actually get it done.”

The original museum was on the outskirts of the French capital, and as a result, didn’t attract many visitors, so in 2014, he moved it to a former men’s tie factory in the Marais district of the city, calling it Cardin’s Past-Present-Future Museum — which has since shuttered.

He recalled at the time, “Before, people thought my taste was crazy. I won’t name names, but some of my peers were very cruel toward me. I can’t tell you what they said and wrote, but they did not understand me. I was different, a nonconformist — like a magazine doing very provocative things, compared with a traditional newspaper.”

Now he said, in one day, “Seven people called out to me in the street, to call out, ‘Bravo, Mr. Cardin!’ with a thumbs-up gesture.”

As for museums in general, he said, “I’ve been to all the museums in the world. Some people go to find something to copy. I went to make sure I wasn’t copying anyone. That’s what I understand when I see my work together here. I’ve always done my own thing.”

See Also:

Pierre Cardin Documentary Screened at Venice Film Festival

Pierre Cardin Stages 70th Anniversary Show

Launch Gallery: Designer Pierre Cardin Dies at 98, Life in Photos

Best of WWD

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.