Patrick Mahomes Doesn’t Take a Day Off

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

PATRICK MAHOMES II doesn’t need to train right now. But at this exact moment, more than anything, he wants to. It’s 7:03 in the morning on July 7, 2020, and he’s nearly alone in the cavernous Athlete Performance Enhancement Center (APEC) in Fort Worth, Texas. He’s less than 24 hours removed from signing his ten-year, $503 million pact with the Kansas City Chiefs. But in his mind, his standing as the face of the NFL and the owner of the richest contract in U. S. pro-sports history is already irrelevant. Two days prior, when he was summoned to KC for the physical exam and presser that come with every historic contract, he planned this very workout. And he texted Bobby Stroupe, his trainer since childhood, a promise: “I’ll be back Tuesday to work.”

Time to deliver. Mahomes accepts Stroupe’s congratulatory hug, then jumps into his workout. His training mixes high-tech ideas (he opens by kneading his legs with a massage gun) and a simplicity that allows him to go balls to the wall. Mahomes isn’t a freak athlete. He relies on a cocktail of flexibility exercises and explosive movements to develop the athleticism needed to excel on the field.

He goes through a multidirectional leap-and-hop series, then grabs a med ball, squats down, explosively leaps a foot in the air, and heaves the ball over his head, 30 yards down the turf. Laser-timed sprints come next, and then Mahomes steps into a Keiser squat machine. A Keiser machine looks a lot like a standard weight machine—minus the weights. Instead, it uses a unique brand of pneumatic resistance that can fully absorb the weight-

rattling explosive oomph you sometimes hold back with standard free weights or machines. Mahomes leans his shoulders against the contraption’s rubber pads, squats low, and delivers three rapid-fire reps of oomph. Each time, the machine bounces off the floor.

Two hours and one sweat-soaked T-shirt later, Patrick Mahomes has worked. He’s muscled through 23 different exercises and thrown about 40 passes in a workout that sets the tone for his new 24/7 fitness lifestyle. For years, he’d trained hard. But last off-season, motivated by Stroupe, he took a holistic view of fitness: fine-tuning his diet, optimizing his rest, and embracing and exploring advanced recovery treatments in an effort to drive his training to the next level. “I had to find a way to make myself better,” he says later, remembering that Tuesday-morning workout and possibly every other session these days. “It’s trying to find the next step.”

It’s always been about what’s next for Mahomes, who, at 25, is four years into a career that has commentators struggling to find enough superlatives to do it justice. He doesn’t stand and survey the defense; like an NBA point guard, he probes and penetrates it, searching for a target or a lane. Other QBs set their feet for each throw; Mahomes plays a perpetual game of on-the-run darts, wrist-flicking screens and 50-yard bombs alike. He’s basically unguardable. In 2018, his first year as a full-time starter, he became the third QB ever (Tom Brady and Peyton Manning are the others) to throw 50 touchdowns in a season and won MVP. The next season, he won his first Super Bowl. In November, he became the fastest QB to reach 100 career TD passes.

Through it all, Mahomes has gotten more and more obsessed with optimizing his fitness, because he knows that fitness is the key to the success and career longevity that GOATs like Brady, 43, and Le-Bron James, 36, are currently stretching beyond what was ever thought possible. It also offers a kind of cultural power—a platform, in brandspeak—to help him make his mark on a country that is increasingly looking to its athletes to be activists and inspirations. For Mahomes, the son of Major League pitcher Pat Mahomes, who is Black, and Randi Martin, who is white, an opportunity to test that power arrived last summer, when he added his influential voice to the nation’s social-justice conversation and instantly became a key figure in 2020’s athlete awakening. (A lot more on that later.)

But Mahomes knows better than most that success and influence can be fleeting. In 2000, while playing with the Mets, his father helped advance the team to the World Series. “I got to see him battle and grind to try to get back there,” Mahomes says today. Pat Sr. never reached the playoffs again. “You never know if it’s going to be like this for the rest of your career,” Mahomes says. “So I try to win as much as possible now, and do whatever I can to win multiple Super Bowls. I’m at the right point in my career where I can use my voice and people can really, really make an impact in this world. This year, with everything that happened, it prompted me to really be bigger, and then be more than I had been before.”

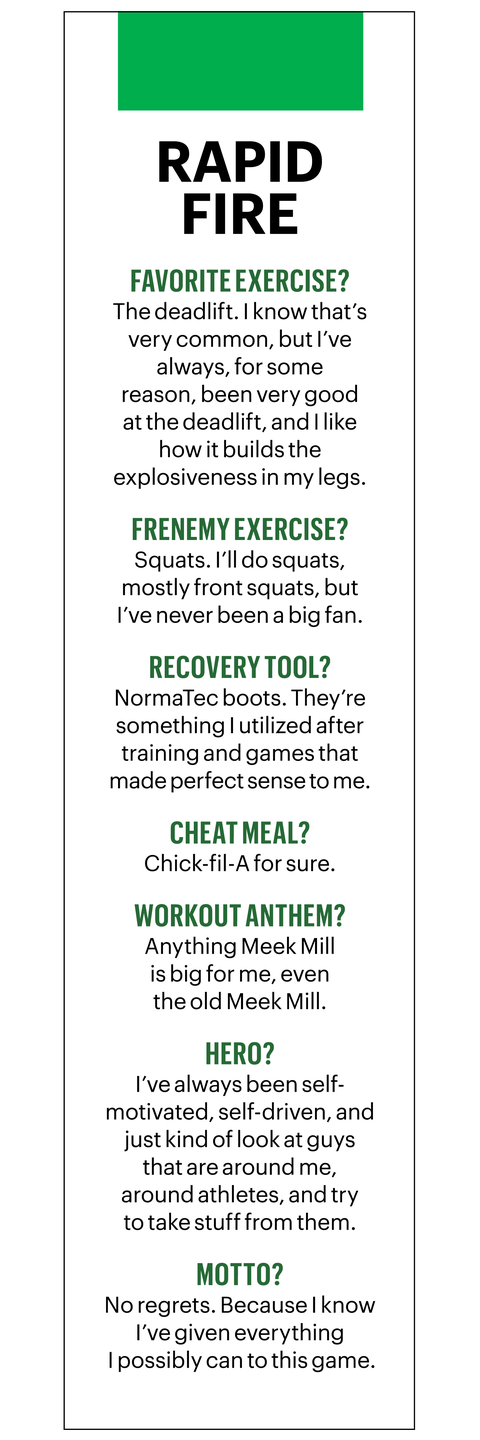

Mahomes wants more. The closer he creeps to GOAT status, the more we’ll all listen to his message, the same way we hang on LeBron’s every tweet and overanalyze Brady’s baseball caps. But it takes far more than three great seasons to attain that. (Remember Daunte Culpepper and Joe Flacco? No clue who they are? That’s the point.) Mahomes has studied the greats, both at his position and across sports and genres, because he wants to stick around. He’s spoken to Donovan McNabb, the first quarterback to thrive under Chiefs coach Andy Reid, back when Reid ran the Eagles. Mahomes’s fiancée, Brittany Matthews, has been with him since they were in high school and says he looks up to Dwyane Wade and Kobe Bryant, both of whom played into their late 30s. (Mahomes also says he loves Meek Mill, specifying that he listens to “even the old Meek Mill,” too.)

He knows legends dominate across multiple acts. “I just always wanted to find a way to be on top at the end of the day,” says Mahomes. “I was able to do that early in my career. And I’m gonna try to continue to get back to that feeling again.” To make you listen, Mahomes believes he must keep winning. And to keep winning, he’s convinced he must train harder.

THE CHIEFS HAVE the day off. Patrick Mahomes does not. (Notice a theme here?) It’s an early-December Tuesday and he’s in an empty gym with Stroupe. Two days earlier, the Chiefs beat the Broncos, clinching a playoff berth and a shot at a Super Bowl repeat. But Mahomes wasn’t sharp, throwing just one TD pass. Stroupe texted him afterward, telling him to make quicker decisions. Mahomes, as he’s done several times this season, asked Stroupe to run him through a session.

It’s a play right out of the Book of Brady, who once had his own trainer, Alex Guerrero, roaming the sidelines at Patriots games. Stroupe isn’t Guerrero (he is a qualified C.S.C.S. strength trainer who runs his own business, APEC, and has a host of MLB clients, including Colorado Rockies all-star Trevor Story), but he is integral to Mahomes’s new focus on total fitness. He’s worked with Mahomes since the quarterback was a fourth grader in Whitehouse, near Tyler, Texas, and Stroupe knew enough back then not to mess with the boy’s unique physicality. While other kids in Texas’s football hotbed headed to QB camps, Mahomes grew up playing not just football but also baseball and basketball, and he never learned that there was any one way to throw a ball. He just learned to get the ball to targets, whether as a shortstop whirling and throwing to first base or as a point guard throwing a no-look pass. “I almost learned the quarterback position backwards,” Mahomes says. “That was the reason I play the game the way I play.”

Stroupe understands Mahomes’s literal strengths and weaknesses. “Let’s just be honest: He’s not a Greek god,” Stroupe says. “If you look at his anatomical setup, his body is built like a reverse centaur. He has a really big upper body and a triangular, smaller lower body.” That limits the amount of leg drive Mahomes can create on his throws. And there’s Mahomes’s spine, which Stroupe says is “the most athletic spine I’ve ever seen.” Mahomes can explosively twist and turn his upper body any which way, meaning the NFL’s priciest player is basically Gumby.

As if to prove his flexibility on this particular day, Mahomes works through what Stroupe calls the “chunk drill.” The objective is to lunge in one direction while twisting your torso as violently as possible, aiming to look straight behind you. Most athletes fall short of that goal. Mahomes moves like a creature out of The Exorcist. Football vise-gripped in his right hand, he stands facing Stroupe, then rotates his hips 180 degrees counterclockwise and

genuflects on his right knee. “Spin it,” Stroupe says. Somehow Mahomes’s upper body keeps whirling. He ends with his face almost looking back at Stroupe (creepy, we know) before reversing the process. This uncommon mobility means Mahomes can create upper-body spring by arching through his spine or twisting quickly through his shoulders to make his masterful on-the-run throws.

Stroupe’s training consistently builds on all of this. He’s known for a series of drills that challenge total-body mobility (like the chunk drill). These help Mahomes move better without packing on more muscle than he needs. Stroupe also loves med-ball movements, which are effective at challenging the spine.

Mahomes has realized that the in-gym workouts are just a starting point. Much of the summer was about fine-tuning how he supports his training outside the gym, blending a personalized nutrition plan with more time spent recovering his muscles with infrared-sauna sessions, massage guns, and NormaTec air-compression boots. (He also puts his money where his muscle is: Mahomes has investments in data-tracking powerhouse Whoop, recovery-gear giant Hyperice, and sports-nutrition brand BioSteel.)

When Mahomes decided to overhaul his fitness last summer, Stroupe knew how to direct him. First, Mahomes was tested for allergies so he could calibrate his diet (verdict: he’s allergic to “most nuts” and grass), then he hired a personal chef. He also donned a Whoop band, streaming all his personal data directly to Stroupe’s phone. Stroupe zones in on Mahomes’s recovery score (a Whoop measure of how well his body recovers while he sleeps). It’s calculated using resting heart rate, respiratory rate, sleep quality, and heart-rate variability (an analysis of the time between heartbeats). Based on those numbers, Stroupe advises Mahomes on his training intensity. He’s developed his own targets for Mahomes and chases consistency, especially when it comes to recovery scores. His goal: keep Mahomes between 40 percent and 80 percent recovered every day. Yes, that’s better than a full recovery (100 percent) or a complete in-the-red crash. “It’s not good if he’s on either end of the spectrum,” says Stroupe.

This is all exactly what Mahomes wanted. “I told Bobby just to continue to challenge me, continue to bring different stuff,” he says. “He’s really helped me execute at an even higher level on the field.”

This past summer, when the pandemic was at its height, Mahomes found himself stuck at home, and with Stroupe grounded in Texas, Mahomes turned to another trusted fitness source: his fiancée, a certified trainer with a degree in kinesiology who’s already built her own fitness brand, Brittany Lynne Fitness. Matthews drew up his workouts, and Mahomes rose at 6:00 every morning and coaxed her out of bed so they could train alongside each other.

The training arrangement didn’t last long, especially once the season arrived. Matthews is pregnant (the couple is expecting a daughter soon), so Mahomes has worked to minimize any chances of her getting COVID. After the Chiefs beat the COVID-stricken Patriots in October, Mahomes slept in a separate bedroom and wore his mask around the house. “We’ve had to do that a few times,” says Matthews. “But he also gets tested every day up there [at practice]. We’re both just respecting each other.”

Between his trainer, his fiancée, and his own drive, Mahomes has never been stronger or faster. Three years ago, he carried 237 pounds on his six-three frame. This year, despite COVID restrictions that limited one-on-one sessions with Stroupe and curtailed access to the Chiefs facility, he sits between 224 and 228 on game days. He feels ready to achieve his ultimate goal, which Stroupe knows well. “Maaaaaaan,” Stroupe says, “he’s chasing legacy.”

MAHOMES ENTERED the NFL in 2017, just as players were starting to express frustration over the issues plaguing the country, and Mahomes didn’t jump headlong into the conversation. His godfather, the ex-MLB pitcher LaTroy Hawkins, advised him to wait. “My conversation with him was: ‘You’re new to the league,’ ” Hawkins says. “ ‘Your main objective right now is learning this playbook and building leadership skills.’”

During Mahomes’s first few years in the league, his play gave the lie to decades of unfair racial stereotyping that dogged every Black QB since Fritz Pollard a century ago. Scouts love labeling styles: Black quarterbacks are often “athletic scramblers,” white QBs “polished passers.” But Mahomes defies those labels and underlines their spurious nature. On any given down, he can throw the prototypical deep ball or yet another what-the-hell pass threaded through three hapless defenders.

The most powerful platforms are rooted in the strongest performances: The moment you stop winning, everyone can opt out. The biggest thing that Colin Kaepernick had going against him and his career in the NFL was timing: Kaepernick began kneeling in protest of police brutality in 2016, months after a series of surgeries and three years after his only Super Bowl appearance, so his detractors conveniently dismissed him as “in decline.”

But when history came for Mahomes last June, following the death of George Floyd at the hands of police—the ugliest moment of 2020, according to Mahomes—he was a Super Bowl MVP and very much on the rise. Mahomes couldn’t bring himself to watch the eight-minute-46-second video in full. He still struggles for words when discussing it. “I mean, seeing that video, I mean, you can barely watch it,” he says, voice dropping low. He slows down, choosing his words carefully. “You have to stop the video because, I mean, it’s just sad to watch. And being from a racially diverse family, I could see someone in my family being in that position. And so I just didn’t want that to happen again.”

He didn’t publicly speak right away, and those close to him indicate he was conscious that his biracial background could undercut anything he said. He’d lived a childhood of privilege, enjoying three parental figures in his father, his mother, and Hawkins, his godfather. He spent time in MLB locker rooms with his father, then relaxed with his mother at home. And when his parents divorced in 2006, they made sure Mahomes never had to choose between families. Mahomes lived with Martin, but his father was always “at school, at practice, at every game,” Hawkins says.

Mahomes moved freely through multiple worlds, enjoying the best experience a biracial child could, making friends with both Black and white children, Hawkins says. He was never forced to label himself as Black or white. “I don’t want him put in a race box. When you put him in a box, you completely ignore his momma,” Hawkins says, bristling slightly. “He’s the product of a Caucasian family and a Black family. They’re both human beings.”

But in the wake of Floyd’s death, Mahomes was angry and wrestling with his duality. He spoke with Hawkins, who is Black and works not far from where Floyd was killed in Minnesota. “He was very disturbed, just like everyone else,” says Hawkins.

But Mahomes decided he could no longer just be “everyone else.” On June 1,

he released a Twitter statement, acknowledging first that he was “blessed to have been accepted for who I am my entire life” but adding that “this isn’t the case for everyone. The senseless murders that we have witnessed are wrong and cannot continue in our country.”

Days later, he’d appear with other players in a social-media video hashtagged “StrongerTogether,” saying directly into the camera, “Black Lives Matter.” Less than a week after that, Roger Goodell, the NFL commissioner who let Kaepernick get run out of the league, uttered the words “Black Lives Matter” in a video statement. Then in August, he went further, saying in a social-media interview that the league “wished we had listened earlier” to Kaepernick’s kneeling protest. And sure, it was a standard, corporate fake apology. But after Mahomes joined the discussion, the league finally shifted its political agenda.

He eventually had a meeting with Goodell with the goal of urging the league to back up its talk. “I got to talk to Goodell. I talked to other guys around the league,” he said on Fox Sports’ Undisputed in August. “Obviously, now it’s about action. I’m excited that we’ve had these conversations, but now it’s about going out there and acting on it.” It’s always

about what’s next.

PATRICK MAHOMES IS already moving past this season. Because as brilliant as his 2020 was, he’s already hunting for his next steps for growth and new ways to stay on top.

In a decade (or two maybe?), Mahomes wants you discussing him the same way you talk about Brady and LeBron today. “Those guys, they’ve prolonged their careers,” he says. “And if I start early, I’m trying to get myself as much opportunity to go out there and be at the top of my game for the longest amount of time possible.”

In the coming days, there will be a conversation with Stroupe. Trainer and quarterback will discuss new off-season goals and find other lifestyle tweaks they can make to drive even better performance. Stroupe already thinks Mahomes can add speed and power, and Mahomes believes he can become a more consistent performer. The 2020 season has just finished, and Mahomes is already on to 2021. “To me, if it’s not broke, it’s not broke,” he says. “We’ve continued to build this plan and continued to get better and better.”

This story appears in the March 2021 issue of Men's Health.

You Might Also Like