Pariahs or patriots? How The Dixie Chicks became the most hated band in America

It was 2003, and The Dixie Chicks were backstage, midway through their record-breaking Top of the World Tour. But Martie Maguire, the trio’s violinist, was melancholy. As she said to her bandmate, frontwoman Natalie Maines, after they came off stage: “All these people in this arena, and I thought: Are we ever going to be at this level again? It made me so sad. Is this the top?”

The past 17 years have suggested that yes, that really was the peak of The Dixie Chicks’ success. At least it was quite some peak: during the 1990s, the group were Sony’s cash-cow, shifting 10 million copies of each of their first two chart-topping records. By the turn of the millennium, thanks to the kind of leverage that accompanies back-to-back number one singles, the group had signed a deal reportedly worth, to each member, $20 million (£15.4 million) and a 20 per cent royalty share.

But this summer may prove them capable of multi-million-dollar tours once more. The Texan trio on whom conservative America turned its back are returning, with a new album called Gaslighter. Originally scheduled for March, before Covid-19 arrived, it will now be released on July 17.

And so, 14 years after their last studio record, and nearly 20 after a fall from grace unprecedented in the industry, Maguire, her sister Emily Strayer (then known as Robison) and Maines may at last recover from country music’s most savage abandonment. The key difference will be their name. Completing their break with their original Southern US roots, “Dixie” won’t be part of it any more. Enter, instead, “The Chicks”.

The name of the Top of the World Tour wasn’t meant to be so literal. Sold out six months earlier, to accompany yet another of the country band’s chart-topping albums, the tour irreversibly changed their fortunes instead. On its opening night, at Shepherd’s Bush Empire in London, frontwoman Maines let out some mid-song patter that would transform The Dixie Chicks from America’s highest-selling all-female group – a record they nonetheless hold to this day – into pariahs.

It was March 10. The band were in London on the eve of the second Iraq war. Three weeks earlier, 1.5 million people had clogged the streets in protest. While The Dixie Chicks hailed from the notoriously conservative state of Texas, they had never clung to its political loyalties. And so, on stage, after finishing their latest chart-topper, Travellin’ Soldier, Maines told the crowd: “We’re on the good side with y’all. We do not want this war, this violence. We’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas.”

To watch the moment back is to see how unrehearsed it was. Maines, eyes bright under her towering trademark quiff, spoke softly, even hesitantly, as if she were only thinking of what to say as she said it. When she was done, the crowd roared back in approval. She gave a broad smile and moved away from the mic to let out an overwhelmed laugh.

There was a brief delay before the impact. The next day, her line was loaded into the second paragraph of The Guardian’s three-star review of the gig, which painted the band – albeit with admiration – as country’s controversialists. “At a time when country stars are rushing to release pro-war anthems,” said the critic Betty Clarke, “this is practically punk rock.”

This was the year before Facebook turned up; two before YouTube did. Maines’s statements would have remained rock ’n’ roll rumour – The Dixie Chicks were a little-known offering in Britain, then largely ignorant of the country genre – had the Associated Press not picked up that review and delivered it to the global press.

A few days in, the band were giddy on the start of their tour, and the band’s manager Simon Renshaw struggled to interrupt their giggles when he told them what was happening. He had taken their websites down, he said, and they would need to prepare a statement. In footage from their 2006 documentary, Shut Up and Sing, you can see the gloom descend on the women’s faces. His eyes glinting from the silver lining, Renshaw, an LA-honed Brit, posits: “Wouldn’t it be great if we could get them burning CDs, banning you from the radio?”

It was a prediction that would come to haunt them. While The Dixie Chicks toured Europe, an online-savvy Right-wing group called The Free Republic staged a meticulous campaign against the band, targeting country music’s lifeblood: the genre’s dedicated radio stations across America. Maines’s comments were frequently described as “treason”. Radio stations, who relied on listener ratings for advertising income, realised that to play the increasingly unpopular band would be (as one DJ put it) “financial suicide”. Their airplay all but stopped. Travellin’ Soldier had been at number one; it nosedived to number 63.

And The Free Republic’s efforts hurtled along on the ground. Radio stations set up designated bins in which former fans could deposit their Dixie Chicks CDs. In Louisiana, a carpet of discarded discs was laid, and a tractor ran over them. Furious men told hungry local-news cameras: “Freedom of speech is fine, but you don’t do it out of the country, and you don’t do it mass-publicly!” On Fox News, a pundit described The Dixie Chicks as “callow, foolish women who deserve to be slapped around”.

By the time The Dixie Chicks turned up to the first night of the US leg, in Greenville, California, protestors were lining the streets. Ticket-holders queuing to enter the arena were shouted at: “Support your country, boycott The Dixie Chicks!”

That was in May. By June, the band’s head of security was walking into their dressing room to tell them there were death threats aimed at Maines. The documentary shows him delivering what intelligence the FBI have on the suspect, and presenting her with a mugshot. Maines is having her hair done. She looks in the mirror, taps her fingertips together and replies: “He’s kinda cute?”

But by the time her supposed death-date arrives on July 6, fear has set in. Maines leaves an anxious voicemail for her Tarot reader, asking if she thinks Maines may be in danger. The group fly to the venue stage-ready, but arrive in a police convoy. During the set, Maines gives the crowd 15 seconds to boo, if that’s what they want to do. Instead, rapturous cheering laps over the stage.

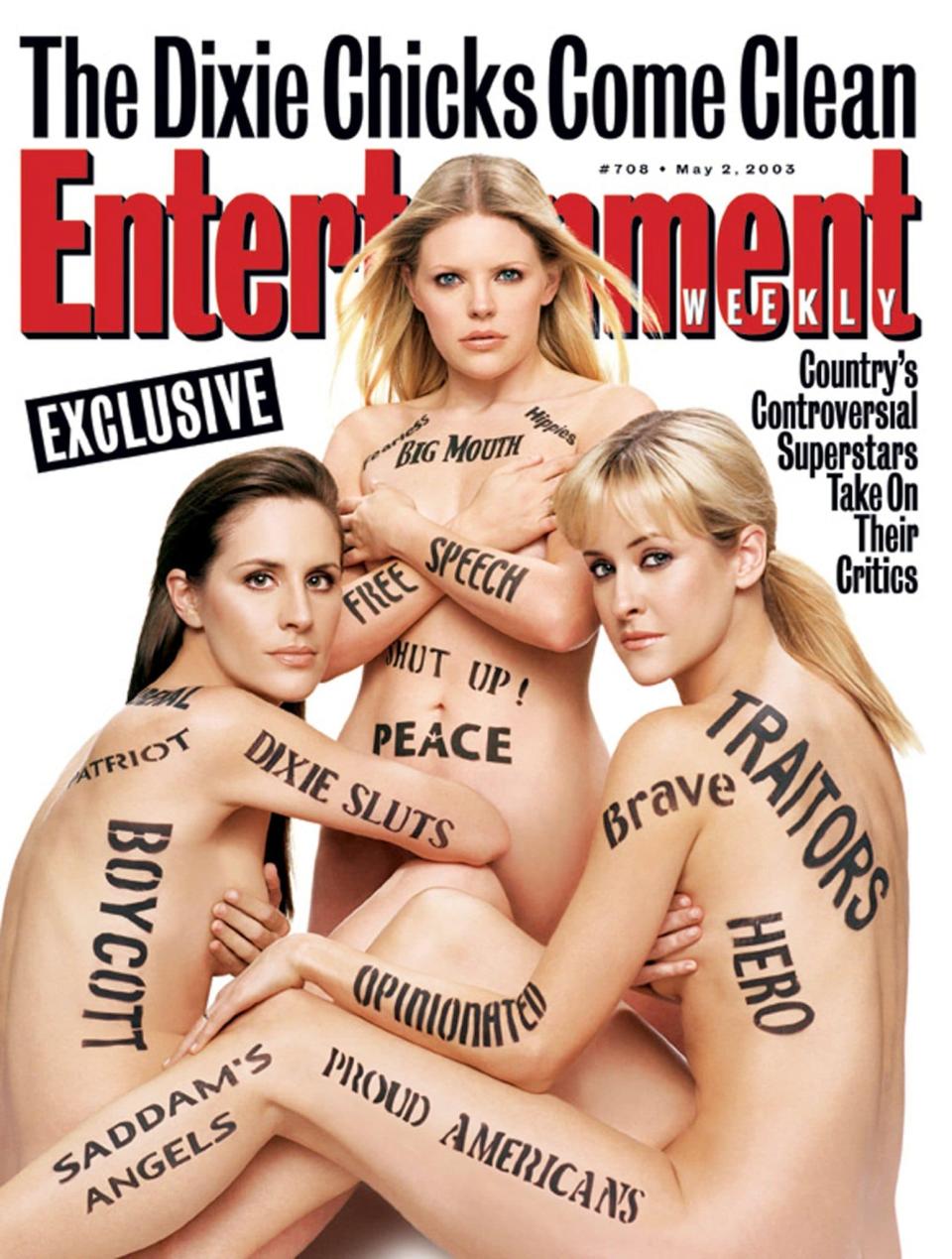

Throughout this whole saga, the band remained defiant. Crisis talks were peppered with Maines’s insistence that she would not take back what she said – that she refused to support the commander-in-chief, or his war. Months before the death threat, weeks before their return to America, The Dixie Chicks graced the cover of Entertainment Weekly for the first time, wearing nothing but fake tattoos of the names their critics had called them: “traitors”, “Saddam’s Angels”, “Dixie Sluts”.

But no amount of defiance could counter the lack of radio play. When asked by a journalist if the furore had taken its toll on the band, Maines struggled to keep the defeat out of her reply: “We can do anything we want now, musically, without feeling any pressure that we have to please – because we don’t have anyone to answer to, as far as radio is concerned.”

Nonetheless, other figures in the music world were watching keenly. The scandal made producer Rick Rubin take notice of The Dixie Chicks for the first time. “Everyone started taking what they said seriously,” he told The New York Times in 2006. “To take a band that’s popular not for that reason and give them that power seemed very exciting.”

Rubin wanted to help The Dixie Chicks take what had happened to them and turn it into music. The trio left for Los Angeles, hunkered down in a cave-like studio among the palm trees and howled into microphones. For the first time in their career, they wanted to write all of the songs on their new record by themselves. “It’s our therapy, it’s what we want to say,” Maguire explained.

They stopped caring about country radio. As Maines later put it: “Do you really think we’re going to make an album for you, and trust the future of our career to people who turned on us in a day?" They looked to other outcasts for inspiration, among them Shelby Knox, who campaigned for sex education in her deeply religious (Southern Baptist) Texan town, and was shunned for it.

The end result was Taking the Long Way, a searing record that sounded more Fleetwood Mac than Western Swing and led with the fiercely unapologetic torch song Not Ready to Make Nice. A single borne out of Maines’s refusal to forgive the fans that turned on her, it relied on rock guitars and directly tackled what had become known as “The Incident”. The Dixie Chicks’ lack of remorse was clear in the lyrics: “It turned my whole world / and I kinda like it.”

Ironically, the record’s release collided with news that vindicated Maines’s disapproval of the war. There had never been weapons of mass destruction; Saddam Hussein didn’t, as Bush claimed, have a “massive stockpile” ready to wreak havoc. Bush’s approval ratings plummeted to 29 per cent. Talk-show hosts clamoured to say that they’d always agreed with The Dixie Chicks, who were busy promoting their new record via television and covering Time magazine.

Despite winning barely any radio play – the band were still dead to country stations – Taking the Long Way still landed at the top of the Billboard chart. It went on to win Album of the Year at the Grammys in 2007.

The Dixie Chicks may have been vindicated on one level, but their rejection by the country world had a long tail. Having dominated the genre, when the trio fell from grace they also wiped out the opportunity for other female musicians to receive the airplay they deserved. In 2003, when their album Fly was atop the charts, female-led songs comprised 38 per cent of the 100 top country songs that year. By 2014, just 18 per cent of the songs on country radio had a female vocalist.

One of the women for whom they paved the way, however, has repaid the debt she owes the band. Taylor Swift has been a fan since childhood and has spoken about how inspired she was by them, not just in terms of their music, but how they grasped control over their entire package – from artwork to public image.

In the Netflix documentary about Swift, Miss Americana, Swift cites the band while fighting to speak out against Republican candidates in her native Tennessee – something that Swift’s team considered career suicide, but the star herself maintained was vital. Ultimately it paid off, showing the breadth of path that the trio paved for country’s future controversialists.

Swift brought the group a new flurry of fans after collaborating with them on her 2019 album, Lover. On the song Soon You’ll Get Better, the group could almost be mistaken for backing vocalists: Maines’s leading peal is soft and melodious over the chorus. Nevertheless, it was the most prominent release they’d had in years.

Until then, the band had long been silent. This wasn’t just because of “The Incident”; toddlers and newborns complicated matters in the early 2000s, and Maines, Maguire and Strayer wanted to take a break from the road to raise their fledgling families. “For the last two years,” Maines said recently, “we’ve rehearsed a lot, but for the 14 years before that, not so much. We’ve all put in our 10,000 hours.”

What’s remarkable is how the sisterhood between the three women never wavered in the wake of Maines’s outburst. A poignant scene in Shut Up and Sing shows Maguire crying as she admits that Maines “still feels responsible”. “I’d give up my career for her to be happy,” she says, “to be at peace.”

Fourteen years on, and a comeback interview suggests that Maines still carries that weight: “I have no regrets,” she told Allure magazine in March, “but the responsible part of me doesn’t want to put people through shit.”

Back in 2003, Maines muttered a kind of throwaway prayer: “The rest of our career better not be overanalysed like this because of this one episode.” Of course, that was exactly what has happened. But what fewer people could have predicted was how well-timed their return could be.

In 2020, we have an American president who makes Bush look like a logical, level-headed statesman, and the discussion around women's rights and voices is more excoriating than ever. A furious album from The Chicks – now arriving without the “Dixie” tag – could be just the balm we need.