Monday Motivation: The Pack Mentality Kept Me Alive Through Cancer Treatment

It doesn’t surprise me that I was on my bike when I first began to hear my body whispering that something wasn’t right. As a competitive cyclist for many of my 48 years, I’ve experienced ups and downs before, and when you train long and hard enough, there comes a time when it’s a struggle to get off the couch.

Last summer, I thought the years of pushing had finally caught up with me. My kick seemed to be losing punch, and when I dragged myself to my regular afternoon group ride near my home in Tampa Bay, Florida, I was often at the tail end of the pack, spinning as hard as I could to not get dropped.

It wasn’t normal, but it wasn’t frightening either. We all aim to ride at the head of the pack and sometimes break away, and when a rider falls behind, there’s usually someone who drops back to pull them up. Slumps happen.

As I always have, I aimed to pedal through this, but I wasn’t recovering. I found myself out of breath all the time, not just on the bike. I figured it was pneumonia, the flu, or worn by age when I went to see a doctor about it in September 2018. As it turns out, what I was experiencing were the first symptoms of something much scarier.

It didn’t take doctors long to figure it out: acute myeloid leukemia, a fast and hard-charging monster that can kill a person in mere months. I was 47 years old, fit, and healthy, so how could I be dying? A month earlier I had been in Oahu, Hawaii, working on a documentary film, and now I was laying in a hospital bed wondering if I’d live.

Being fit turned out to be a positive, at least for my doctor. On that first day, doctors at Moffitt Cancer Center started running genetic tests to determine the type of leukemia and the course of action. When an oncologist looked at my blood work, he couldn’t believe I had walked in on my own two feet. When I told him I was a cyclist, he was thrilled.

This didn’t mean I had a higher chance of survival; rather, the doctor had plans for me: “You’re young and fit because you ride, so we’re going to hit you as hard as we can with chemotherapy.”

It’s not easy to hear your doctor say he’s going to push you to the edge of death because you’re in good shape. But his optimism made me believe I was strong enough for the fight, and if there is any magic in any of this, it is the power of belief.

The next few weeks were a blur. The first few days of treatment weren’t terrible, but by day five, I was vomiting and unable to eat. I was being pumped full of anti-nausea drugs, antibiotics, and anti-fungals. By day seven, I was hallucinating and stopped eating all together. I can honestly say that was the closest I’ve ever been to death, and I was sure I was going to die. The nurses were extremely concerned about my condition, and the nutritionist ordered a feeding tube because I was wasting away.

I was in hell.

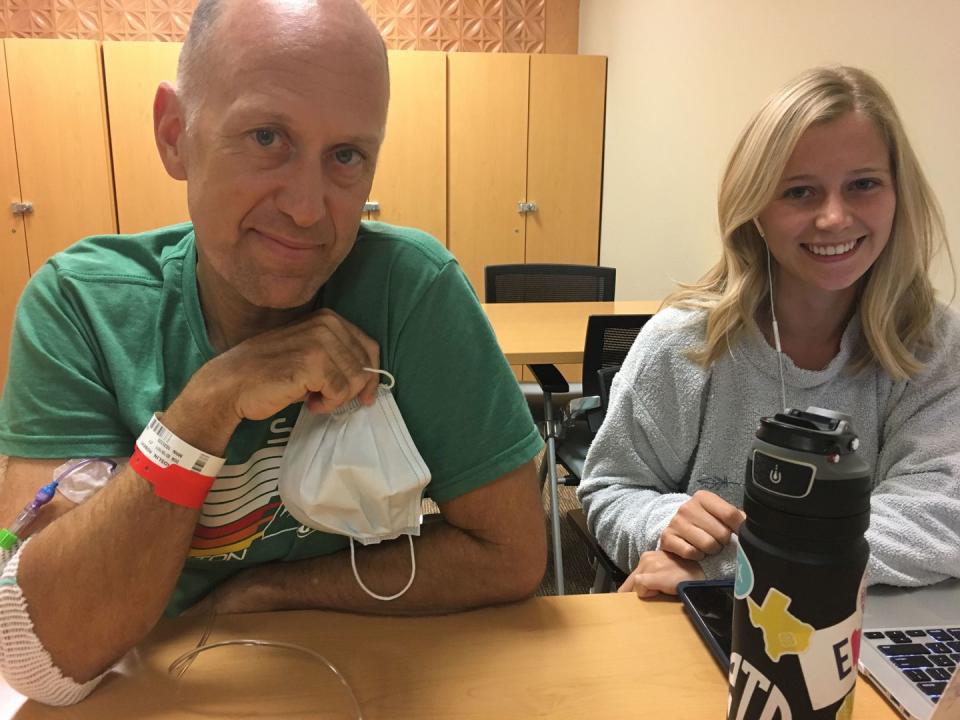

As I laid in bed with my wife, who had moved into my hospital room with me, news of my diagnosis grapevined through the Tampa Bay cycling community. The last thing on my mind was riding, but the same cyclists who fell back to help this struggling rider came to my bedside, bearing concern, help, laughs, well wishes, calls, and texts.

They pulled me back into the pack. This sense of belonging gave me a measure of strength as I faced the seven weeks of pure hell until I was able to start recovering.

Little by little, my strength returned. I began walking the halls, and then the hospital grounds with my wife. My doctor, Ariel Grajales-Cruz, a Columbian oncology fellow at Moffitt, encouraged me to walk the halls as much as possible. Walking was a necessary step in recovery, but I asked him if there was a gym with a recumbent bike I could ride.

The minute he realized I was a roadie, he immediately started testing my world tour knowledge. We started discussing Miguel Ángel Lopez and Nairo Quintana’s Tour de France chances. Cycling was the last item on my mind just weeks before as I thought it was all over. Now, I was on the road to recovery and thinking about cycling again.

Because of my rapid recovery, I was released a week earlier than projected. I walked around the hematology unit giving hugs to all the amazing nurses who cared for me for nearly a month. I still had three rounds of out-patient chemotherapy ahead of me, but as I departed, I asked a nurse practitioner if I could ride. As long as my immune system and platelets had recovered, she said yes.

That was the music my ears needed to hear.

Riding my trainer was the first step back. Because my immune system was still recovering from chemo, I had no immune system, so I couldn’t ride outside. Also, my body couldn’t make platelets, so if I were to fall, I could bleed out from road rash. I wasn’t a quarter of the way through my treatment before I started pedaling again.

So I borrowed a smart trainer from some friends and created a Zwift account. I started slowly, and when I managed 20 or 30 minutes, I was happy. I steadily built up my strength and endurance again until I longed to be back out with the group ride.

That’s when I joined a new group at one of the St. Petersburg Bicycle Club’s morning rides. This group has older riders and maintains more of a conversational pace than my old training pace.

At first, I was back of the pack again, struggling to stay on. Some riders knew my situation and had seen me in the hospital. Others were surprised I was out there killing myself to keep up on a group ride. I was checked on often.

But a few months later, on Christmas Eve, I found my old training group leaving from the same spot as my new group. I didn’t know what to do.

“You should come with us,” my friends from the old group said. “We promise we'll take it easy on you."

Before I knew it, I was doing 24 mph. I managed to stay with the pack, probably because they were kind enough not to drop me over 30 miles.

Being able to finish a ride again with my regular crew, people I care about who had come to visit me in the hospital, felt like a milestone in my recovery, and in my life.

I think my doctors are right, my bike did help keep me alive. It wasn’t just because I was in shape, although that certainly played an important part. It was the freedom, adventure, joy, and sense of belonging that my bicycle gave me that has kept me alive.

And on March 28, after six months of treatment including four bouts of chemo, the doctor gave me the good news: “You’re in remission.”

I weighed 175 pounds when I was admitted to the Moffitt Cancer Center in September. I was 150 when I was discharged. For the first time since I was a kid, I looked at my legs and thought, “Wow. They look skinny.”

But I am back on the bike now and feel strong, and what matters most to me is that I’m riding with the pack again.

Lately, I’ve had these moments riding when I couldn’t help but think, “I am just so happy to be doing this. I am so happy to be alive. And I am just so happy to be on my bike.”

That’s why I want to keep on pedaling.

('You Might Also Like',)