Oprah Talks with Brené Brown About the Power of Being Able to Name Your Emotions

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Megastar author, professor, and podcast host Brené Brown and Oprah first sat down in 2013 to explore the courage it takes to be vulnerable. Brené’s groundbreaking new book, Atlas of the Heart, builds on her 20-plus years of pioneering research to explore and expand the vocabulary of feelings. Oprah and Brené—who have met up many times in the intervening years—recently got together to talk about fear, connection, the state of our country, and much more.

Oprah: Welcome, Brené! The first conversation you and I had together almost nine years ago was also the first episode ever of our Super Soul podcast. And I hear that two-part interview has been downloaded 4.2 million times!

Brené Brown: Whoa!

OW: That says to me that what you’re putting out into the world is something people are hungry for, and you’ve done it again with Atlas of the Heart. You open the book with this epigraph from Rumi: “Heart is sea, language is shore.” Is that the book’s organizing principle?

BB: Our hearts are seas of expansiveness, of emotion, of experience. At some point, those emotions and experiences need to be articulated. Language is a kind of life jacket. But often people aren’t equipped with the words to describe what they’re feeling.

OW: You’ve done a lot of research into that.

BB: Yes. About 15 years ago, we surveyed more than 7,000 people, asking them to compile a list of every emotion within them they could recognize and name. Most people could identify only three: happy, mad, and sad. I found myself thinking, What does it mean if we don’t have a vocabulary that’s as broad and deep as the human experience?

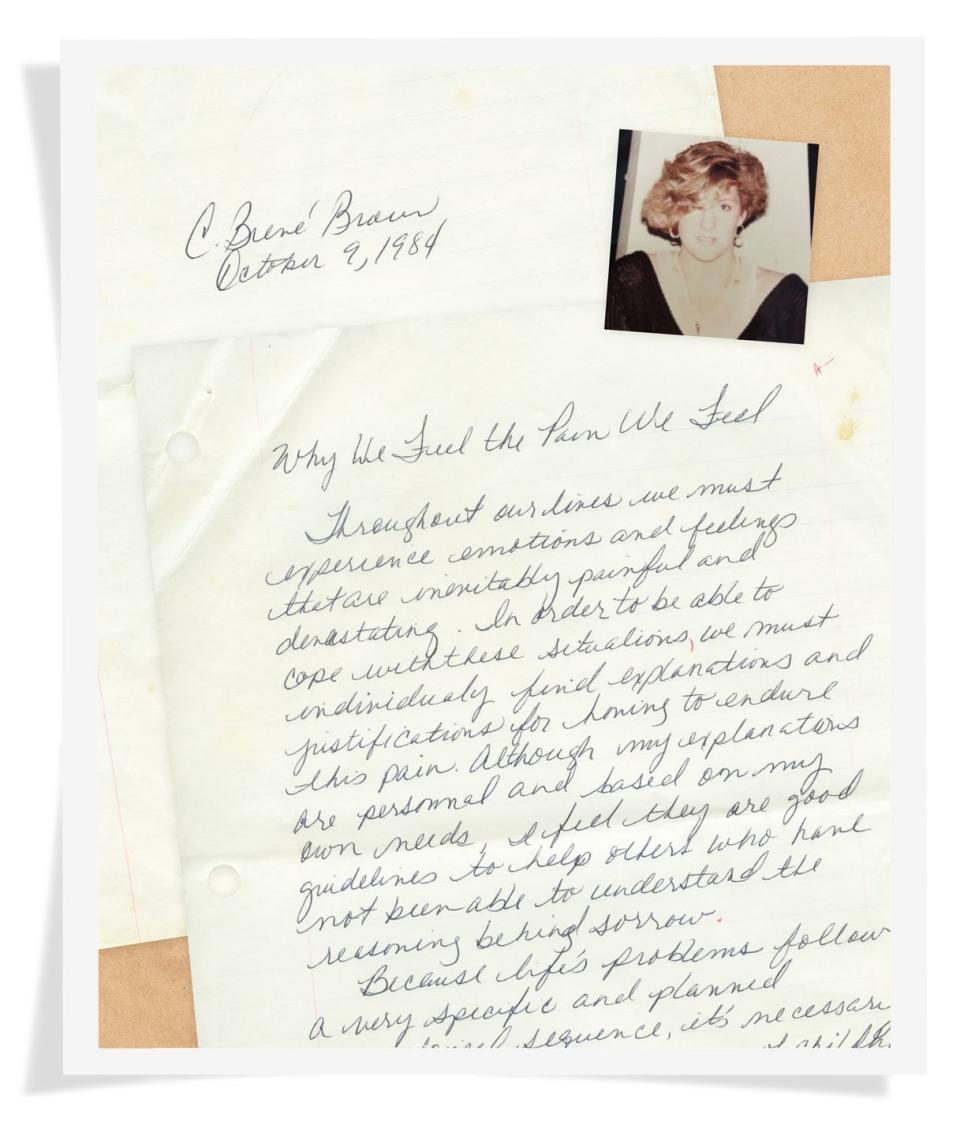

OW: Clearly, you’ve been thinking about a version of that question for a long time. In the book, there’s a picture of you from 1984 alongside an essay you wrote. In it you ask: “Why do we feel the pain we feel?” That was when you were a freshman in college.

BB: Survival for me growing up was about grasping the connection between emotion, behavior, and thinking. As the oldest of four in a volatile household, to protect myself and my siblings, I needed to understand which comments or behaviors were going to kick something into gear.

OW: You found you were good at assessing that, right?

BB: I learned to fine-tune that ability to the point where I could read the room and say, Uh-oh. We’ve got five minutes before all hell breaks loose. Today my therapist would call that hypervigilance.

OW: You call yourself a mapmaker, and the title of your book contains the word atlas. Why that analogy?

BB: I’m obsessed with cartography. In my last three books, I’ve told readers that I’m a mapmaker, meaning: I’m giving you my research and findings to help you find your way. But the truth is, I’m on the road with you. I’m not leading you, I’m stumbling next to you. In this book, I wanted to convey that we’re all mapmakers—we must be the cartographers of our own lives.

OW: So true. For this latest project, you worked with a team of therapists, educators, researchers, students, and community leaders, all sharing experiences around emotion. That must have been powerful.

BB: It all started with you and me several years ago, when we did the e-course “The Gifts of Imperfection.” Upwards of 65,000 people took the course, which yielded hundreds of thousands of data points. The team broke it down to find answers to this question: “What emotions or human experiences are people struggling to name accurately?” The list was long, but eventually we pared it down to a core group of them—about 87—that I dig into in the book.

OW: Why is it important, for example, that we know the distinction between being stressed and being overwhelmed, or as you put it, “in the weeds” versus “blown”?

BB: I quote the German philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in the book, who said: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Language doesn’t just communicate emotions; it shapes them. So when I use a word to describe how I’m feeling, my body will often follow my language. If I use hyperbole and go from saying, “I’m stressed” to “I’m overwhelmed,” often I make that a self-fulfilling prophecy.

OW: What you’re urging us to do is to expand the vocabulary with which we communicate our feelings so we can better understand ourselves and accurately express what’s going on—the right words provide a gateway to psychosocial well-being.

BB: Yes. Imagine that you had an intense pain in your shoulder, but when you got to the orthopedist’s office, your mouth was taped shut and your hands were tied behind your back. You’d be unable to tell the doctor what was wrong. Language is a portal to universes of new choices and second chances. I’ve been studying affect and emotion forever, and yet I struggle with this, especially because I have a super-sensitive nervous system and can use exaggerated—even reckless—language when I’m scared, which is not a setup for successful decision-making.

OW: You talk about a link between shame and perfectionism. That surprised me. Can you explain?

BB: I do all this leadership work in organizations where people don’t get that relationship and intentionally build perfectionistic cultures. And then they say: “There’s no innovation or creativity. What’s going on?” Well, shame kills creativity and innovation; perfectionism is a defense mechanism against shame. If I look perfect, I can avoid or minimize shame, judgment, and blame.

OW: You researched worry and concluded that it isn’t a helpful coping mechanism. But how do we stop ourselves from needless worrying? That’s hard!

BB: Those of us who worry excessively often think it’s helpful, which it’s not, on top of which we believe we have no control over it. Worry is defined as a chain of negative thoughts about bad things that might happen in the future. When you study people who’ve overcome their propensity to worry, it’s all about reality-checking and perspective-taking. In other words, asking ourselves if all the worry is helping or hurting. Do I have enough data to freak out? Even if I do, does freaking out help? The answer is always no.

OW: You write that love and belonging are irreducible needs for all people. And in their absence, there’s suffering. All around us are people in pain, unhappy, angry—who feel they no longer belong. Is that how you see it?

BB: We’re adrift, I think, spiritually, emotionally, physically, cognitively. We’re untethered. The world is unfolding faster than we, as a social species, can manage, and in a way that drives separation. We’ve confused hyper-communicating with actual human connection.

OW: What’s the solution?

BB: We are desperately trying to find safe harbor somewhere out there, but that port is really within us. Meantime, a lot of very smart people see that we’re lost and have created external ports that offer quick, artificial solutions—really a fake sense of belonging and connection.

OW: And those smart people are exploiting that disconnect?

BB: When vulnerability isn’t mutual and reciprocal, it can be leveraged, or, as Anne Lamott puts it, “Help is the sunny side of control.”

OW: How did we get this way? It didn’t just happen overnight.

BB: A lot of people won’t agree with me, but if you don’t turn toward your painful story and own it, it owns you. In this country, if we do not turn toward our collective story around inequality and own it, it will continue to own us. And if you look at the way pain is owning us right now, you’ll see that it’s being leveraged in really destructive ways.

OW: To the point where we literally no longer have a shared reality.

BB: Yes, and that’s by design. There is a school district in Texas now saying that if we’re going to teach the Holocaust, we have to teach the opposite point of view. There is no opposite point of view. This is about a kind of white male power that is maintained by using fear. It’s making a last stand, and last stands are bloody; we’re in the midst of it. What you smell is desperation.

OW: Our systems and institutions are under threat.

BB: Yes; it’s a full-on, daily challenge to democracy, to science, to literature, to history, to education.

OW: How do we re-tether and save ourselves?

BB: The only answer I know is self-awareness.

OW: That’s why Atlas of the Heart is so important, because what it ultimately offers is a greater sense of awareness about our feelings and the tools to articulate them. What do you hope readers will leave the book thinking?

BB: We are emotional beings. Thinking and acting are not riding shotgun—they are hog-tied in the trunk. It’s emotion that’s at the wheel. I did not fully get that before I wrote this book. If we don’t understand our own emotional landscapes, we cannot build a culture of connection.

OW: In the meantime, whose words do you turn to for wisdom and perspective?

BB: I go back to the feminist activist and cultural critic bell hooks, who diagnoses many of us as being bereft due to “lovelessness.” Our abject lovelessness, she says, can only be healed with forgiveness, compassion, community.

OW: Oh, that’s so good! Thank you, Brené.

BB: Thank you, Oprah.

You Might Also Like