No happily ever after: how Succession will end – by the experts

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

And now, the end is near, and so Logan faces the final curtain. The fourth series of Succession, which starts at the end of the month, is to be its last, creator Jesse Armstrong confirmed in February. “There’s a promise in the title of Succession,” he told The New Yorker. “I’ve never thought this could go on forever. The end has always been present in my mind.”

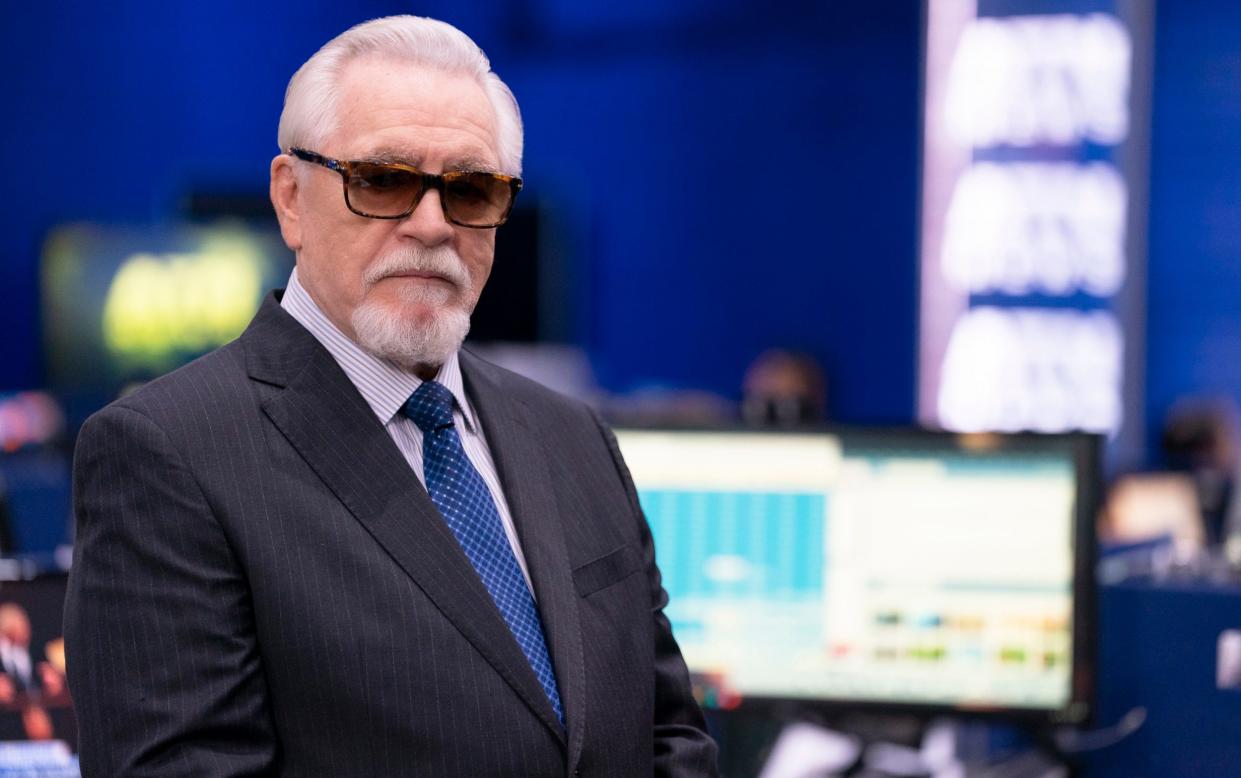

The critically acclaimed, multi-award-winning HBO drama, which sees the adult children of media magnate Logan Roy – played by Brian Cox – jostle to be picked as the chosen one to inherit their father’s sprawling business empire, breaks most of the rules of television: there are no decent heroes and no honourable actions, and it has a narrative goal that most right-minded people find offensive. And yet, when Matthew Macfadyen’s largely derided Tom Wambsgans, husband to Logan’s youngest child, Shiv (Sarah Snook), pulled a fast one on Logan’s offspring at the end of season three, I had at least four text messages simply reading “OMG! Tom!”. We are invested in this amoral war.

Although Armstrong denies the family is based on the Murdochs, Elisabeth Murdoch has been spotted in a “Team Shiv” T-shirt and rumours that her brother Lachlan is about to be thrown under the bus in the Fox News vs Dominion lawsuit echo a plot involving Kendall (Jeremy Strong) in the first series. Real-life parallels abound – just Google “Sumner and Shari Redstone”.

But what is the ever-present end that Armstrong has been planning all these years? We asked five leading experts in various fields – from finance and TV drama to Shakespeare – to look into their crystal balls and industry textbooks and tell us how the show will wrap up. The answers are grim but, as Cousin Greg (Nicholas Braun) might say: “If it is to be said, so it be, so it is.”

Joseph Sassoon

Member of Sassoon dynasty and author of The Global Merchants

People always say success is being in the right place at the right time. The problem is, there are usually 15 people in that place at any given time, and only one can be successful. The more success that one person has – in this case, Logan Roy – the greater their feeling that they are the only one who could do it. In other words, they’re a megalomaniac. Diminishing or undermining the son or daughter is part of their psychology. With the 19th-century Sassoon dynasty (the “Rothschilds of the East”), David’s second son, Elias, brought in by far the most profit, opening new trade routes in China after the Opium Wars, but the crown still passed to the eldest son, Albert, and it split the family in two. Watching the first three seasons, Shiv is the most capable. Realistically, I think Logan has no one except her to pass the business on to. However, I don’t know what he’s going to do with her baggage of a husband. He should let her inherit but force her to divorce Tom.

Steven Moffat

Screenwriter of Sherlock and Doctor Who

Ending every TV show is a problem – fundamentally a TV show’s job is to come back next week. A film is about a hero who has a problem they have to solve, but for a TV show to keep going, the hero has to have a problem that can’t be solved. Succession is very funny and beautifully played and Jesse is a comedy writer. Comedy writers, having found a situation, don’t want to let it go. That’s why at the end of every episode of Dad’s Army nothing has changed. Succession is like that. The inciting incident – the death of Logan Roy – doesn’t actually happen. Logan doesn’t die. Then for the characters, nothing happens, no one has changed their views, no one learns anything – it’s a sitcom and to hell with drama textbooks. In fact, it’s like real life – unlike the movies, most of the time people don’t move on very much, and if we do we don’t like it. As a result, Succession wouldn’t suit a giant twist or a secret relative suddenly revealed. They can only remain in this complicated, perfectly observed, fossilised family. I would end it on a cliffhanger. Any conclusion would prove disappointing.

Mark Borkowski

PR expert and author of The Fame Formula

Succession is not just a high-quality drama – it is also chillingly accurate. In my career I’ve had direct experience of powerful egos such as Logan Roy. They’re not normal. You can’t chat about football with Bezos or Musk. Last week I was working with a prominent property developer. Because he didn’t choose to do what his father wanted, his father created a competing business, put his brother in charge, and cut him out of his will. A few years ago, I had to act for someone plagued by tabloid headlines and discovered that the leaks were coming from a family member – and one who didn’t need the money either. Trust inside those families is absent. But sometimes you can see why the patriarch despairs. I know a “Kendall Roy”, someone who has sunk so much money into cryptocurrency and, like Connor Roy (Alan Ruck), fancies funding his theatrical girlfriend. The sons of the super-rich are always planning vanity projects for their girlfriends. The patriarch is usually a self-made man, his kids are born into privilege and wealth, and they become the kind of people he hates. The accuracy of Succession in depicting these people rules out any kind of happily-ever-after. If this was the real world, Logan would destroy them all.

Emma Smith

Professor of Shakespeare Studies at the University of Oxford

There is clearly a King Lear parallel here – Logan Roy’s name is basically a play on that, with Brian Cox steeped in Shakespearean patriarchs. In general, Shakespeare has four broad endings: a tragedy, where everyone dies; a comedy, where there’s a sense of future that is better than the past; a history, where there’s a sense of future that’s the same as the past; and some of the later plays, where it was all a dream. The clues we’re seeing in Succession are drawn from tragedies – but I think that’s a fake out. It feels to me like a history play where they’re trapped in a cycle, characters jockeying to become the king or the star, to dominate politically and theatrically with all the good speeches. Logan is holding onto that role – but there’s a lot of people vying to take over not only the power but the best lines. My sense is that this ending is determined by human agency – not fate or destiny. Succession doesn’t have magical intervention built in. What I always like is an unresolved ending. I don’t mean leaving the door open for another series – a sense, like the history plays, that these are just scenes from an ongoing story.

Billie Dunlevy

Therapist and member of the BACP

The sad truth is that the abuse in the Roy family dynamics isn’t that far removed from most of the severely dysfunctional families I deal with. (Apart from the helicopters and wealth, and maybe the wit is sharper.) Logan is an abusive narcissist. He abuses his kids to encourage a lack of trust in themselves or each other, and he steals people’s energy as his supply. Poor Roman (Kieran Culkin) is constantly dancing about trying to entertain him, while Shiv is always doing the things he should be doing. With my therapist hat on I would love the siblings to take over the company, get some therapy and deal with their experiences. Roman may wobble – he has a fragile sense of self and a needy relationship with his father so he’s most likely to bail on any rebel alliance. Kendall is the most likely cycle-breaker – when his dad sacrificed him in season three he started to spot the dysfunction. They need to usurp Logan. With him in place, it’s hard to stop the games and dynamics, but with him out of the way, healing is possible.

Series four of Succession begins on Sky Atlantic on March 27