In the Nixon Years, Conspiracy Thrillers Reflected Our Anxious Times. Where Are They Now?

Let me start by saying that if you’ve clicked on this essay looking for objectivity, you’ve come to the wrong place. So with that disclaimer out of the way, here it goes: There hasn’t been an administration as paranoid and corrupt as this one since the dark days of Richard Milhous Nixon. In the early ‘70s, between the escalating mess in Vietnam, the president’s infamous list of enemies, and the granddaddy of all bone-headed Black Ops, the Watergate break-in (and subsequent cover-up), Tricky Dick and his band of dim, dime-store henchmen made it impossible to keep buying into in the greatness of America. Back then, it seemed like if you didn’t trust the government, you weren’t being neurotic, you simply weren’t paying attention to the headlines.

Nixon’s inevitable downfall, as pitiful and self-inflicted as it was, might have been a black eye for the country. But three thousand miles away in Hollywood, it was the stuff of popular mainstream entertainment—an excuse to turn our sins into lasting cinematic art. Back then, citizens were depressed and disillusioned. But they could still go to theaters to see their fears and frustrations reflected back at them. The result was a string of vise-tightening political conspiracy thrillers that trafficked in deep-seated suspicion and mistrust, populated by underdog heroes unafraid to speak truth to power—that is, if they could make it to the end credits with their lives. The list of paranoia-drenched films made during that decade still resonate today—films like The Conversation, Serpico, Marathon Man, Capricorn One, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers. But I’d argue that the three that still ring the truest today are All the President’s Men, The Parallax View, and Three Days of the Condor, the last of which recently celebrated its 45th anniversary.

It goes without saying that the movie industry today looks almost nothing like it did in the ‘70s. Entire books have been written about this of course, extolling the glories of the New Hollywood revolution that ushered in a brief and thrilling cinematic Shangri La where risks were taken, ugly truths were exposed, and downbeat endings were embraced instead of rewritten wholesale. Compare that to today, where what qualifies as a downbeat ending is having a bunch of Marvel superheroes vanish into ashy dust only to be quickly resurrected in the sequel as if nothing inconvenient had ever happened. But all you have to do is scan the front page of The New York Times on any random day in 2020 to realize that the more things change, the more they stay the same, with Donald Trump cast as Nixon 2.0 in the villain role. So where are all of the movies that wrestle with our current moment the way that All the President’s Men, The Parallax View, and Three Days of the Condor grappled with theirs?

I suppose some of this can be attributed to the current COVID pandemic. After all, Hollywood isn’t making much of anything these days, zeitgeisty or not. Still, there were a couple of years before the coronavirus outbreak when a new batch of conspiracy thrillers could have been greenlit—and weren’t. More than ever, it seems, the business of Hollywood is business. And right now, development execs at the big studios clearly don’t see the profit in mirroring our national bad vibes when they can stick their heads in the sand.

To some degree, I suppose, that vacuum has been filled by quality television (see Watchmen, et al.) and the publishing industry, where every former Trump insider seems to leave the West Wing with a fat advance for a Saul-on-the-Beltway-to-Damascus tell-all conversion memoir. Hell, even Bob Woodward, that Boswellian ghost from political conspiracies past, is back on the bestseller list. Maybe it’s too much to ask, but I wish Hollywood would dig a little deeper and find some of the bravery and balls it had back in the ‘70s when messy truths weren’t dismissed as bitter medicine and box-office poison.

When Alan J. Pakula’s All the President’s Men first hit theaters in 1976, America was hip-deep in the rah-rah throes of the nation’s Bicentennial. If you’re old enough to remember it, red, white, and blue bunting was everywhere you looked that year. Gerald Ford was about to make way for Jimmy Carter in the Oval Office and Paul Anka would host a jingoistic NBC special called Happy Birthday, America, but Hollywood wasn’t about to let Nixon off the hook. Not yet.

Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s literary rehash of the Watergate scandal was still in its first-draft-of-history phase. And while moviegoers already knew all of the passion play’s crooked bit players and jail-sentence outcomes, there was still a devastating punch in seeing it all come to life on screen with Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman tirelessly working their shoe leather into ribbons as they sniffed and double-sourced their way up the food chain to the crook-in-chief in what would become a victory lap for American journalism (we could use one of those now, too).

Seeing the Watergate investigation dramatized so powerfully and in such minute and mundane detail didn’t feel redundant, if anything it felt elucidating. It was (and still is) like watching a tick-tock detective procedural whose end result is well-known but we’re still left hanging on the edges of our seats anyways.

Yes, All the President’s Men is the greatest movie ever made about investigative reporting as a calling rather than a career. But it’s also the greatest movie ever made about the banality and drudgery of digging for the truth, one phone call and library slip at a time. It all but leaps off the screen like a rallying call to arms. That may not be why it’s a masterpiece. But it sure doesn’t hurt. And for a film with too many indelible moments to list, let me cite just one that feels especially poignant and pertinent right now. It comes during one of Woodward’s clandestine parking-garage meetings with his deep-background source, Deep Throat. Played by Hal Halbrook with the perfect mix of pack-a-day world weariness and righteous indignation. Never more so than when he tells Woodward “Forget the myths the media has created about the White House. The truth is, these are not very bright guys.”

Now close your eyes and repeat that line. Sounds familiar, right? Surely, there must be hundreds of senators, congressmen, and cabinet secretaries who are saying the very same thing in private at this very moment. People who have seen the greed, incompetence, and mendacity of the Trump White House up close and personal, but are too scared to speak out for fear of Twitter retribution from @realDonaldTrump at 5 a.m. So why isn’t Hollywood making a movie about that? Where is our great call-to-arms conspiracy thriller now?

All the President’s Men isn’t afraid of being smart. It doesn’t dumb things down for the multiplex Joes. And it’s as thickety as a briar patch with convoluted details and implicit menace. You feel as clever as Woodward and Bernstein for being able to track all of its twists and switchbacks. And that’s good storytelling. But another reason why it still crackles is Redford and Hoffman, who turned a couple of average-looking reporters into Me Decade matinee idols. You would have followed them anywhere because it was hard to be a bigger movie star in the ‘70s than either one of these guys. Unless, of course, you happened to be Warren Beatty….

Just two short months before Nixon resigned, Beatty starred in The Parallax View, his first film since 1971’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller. In the three long years between that Robert Altman film and Parallax, he’d taken a hiatus from acting to lend his celebrity to George McGovern’s presidential campaign. It didn’t do much good. McGovern got creamed by the incumbent Nixon. But there’s no question that his left-leaning political sensibilities made a film like The Parallax View (the second of Pakula’s paranoia trilogy sandwiched between Klute and All the President’s Men) as seductive as Beatty was at the time.

Again, a crusading journalist is the hero. But this time he’s no Woodward or Bernstein. He’s a small-time muckraker who happens to be on hand when a maverick presidential candidate is assassinated atop Seattle’s Space Needle. A congressional commission dismisses the killing as the act of a lone nut, but Beatty’s Joe Frady suspects otherwise, especially after witnesses to the fatal shooting start turning up dead under mysterious circumstances. So he begins sniffing around and stumbles onto a shadowy organization called The Parallax Corporation, which recruits unstable personality types into its web of deep-state chaos.

Less well-known today than either All the President’s Men and Three Days of the Condor, The Parallax View has a freaky and hypnotic pull. It also has some great Hitchcockian sequences of delayed mayhem. But the clincher scene comes after Frady infiltrates Parallax and sits through its acid-test indoctrination video, a slide-show montage of wholesome American images intercut with snippets of carnage, sex, and bloodshed. Pakula’s message couldn’t be more clear if he was using a megaphone: By the '70s, carnage, sex, and violence had become as American as apple pie. Anyone watching videos of police brutality on the news these days would be able to connect the dots with no problem.

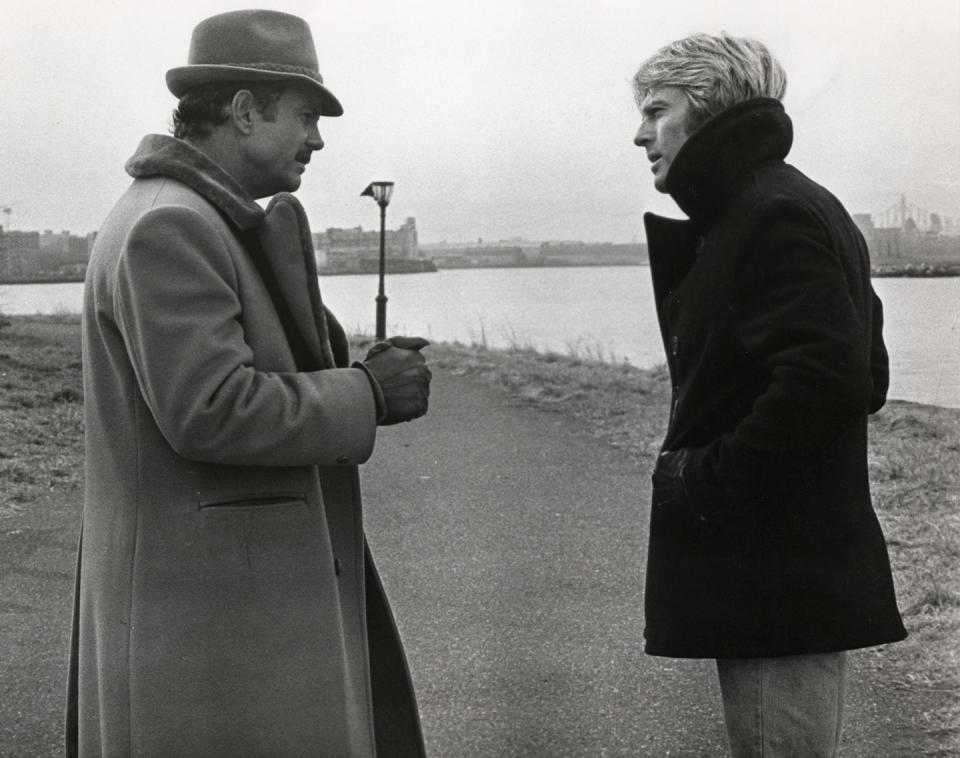

Rounding out the trifecta in the pantheon of dynamite ‘70s conspiracy thrillers is Sydney Pollack’s Three Days of the Condor. Released in late September of 1975, Condor is a lot more melodramatic than The Parallax View or All the President’s Men thanks to its ludicrous sub-plot featuring Faye Dunaway in the implausible role of a woman who Robert Redford takes hostage while running from the CIA. But it’s still dripping with don’t-trust-the-government paranoia and tense dread due in no small part to a chilling banality-of-evil turn from a turtlenecked Max Von Sydow as a grim Euro-assassin.

At the apex of his golden-god box-office stardom, Redford plays Jim Turner—a low-level CIA analyst who basically reads a ton of books in the cloistered office of a Manhattan brownstone hunting for subliminal clues connecting to global malfeasance. After stepping out for lunch one day, he returns to find his entire field office murdered. He phones his CIA higher-ups and begs to come in from the cold, but it turns out that they’re the ones behind the massacre.

Three Days of the Condor is a first-rate thriller that messed with Americans’ faith in its most powerful institutions. That wasn’t exactly a big stretch at the time. And Redford’s hunted Everyman character feels like he could be anyone one of us who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time and witnessed something he shouldn’t have. His Turner is a man whose own taxpayer-funded employer considers expendable in its will to underhanded power. A casualty in a rigged game, who won’t stop running until the truth comes out.

Watching any of these films right now carries a frosty frisson of deja-vu. In the ‘70s, Americans who bought a ticket to any one of these films didn’t think what was happening on screen was that far-fetched or impossible. These weren’t some unbelievable James Bond fantasies with colorful outsized villains. They knew better. These movies felt possible, even probable, because that’s what the government had become—a collection of duplicitous institutions that had violated our deepest trust.

Today, the villains are just as colorful and outsized. Hollywood may not be making movies about them anymore, but they haven’t gone away. If anything, they’ve become emboldened. The movies need to fill that void, and the sooner the better. Because Deep Throat’s warning is just as true right now as it was in the ‘70s: “The truth is, these are not very bright guys.” The only difference is, back then we at least we got some damn good movies out of the nightmare.

You Might Also Like