How the NBA Built Its Bubble Courts

The extensive measures taken by the NBA to create a secure, coronavirus-free bubble in which to conclude its season have been well-documented and, so far, remarkably successful. But the process the league went through to build enough courts to host 22 teams, and make them safe, was in some ways just as complex a challenge. The Disney World ESPN World Wide Sports Complex in Florida, where the playoffs are taking place, already housed seven hardwood floors that could be used for practice, but the NBA needed to build another seven practice courts, two half courts for shooting, and three game floors that are elegonated for social distancing.

First, the NBA had to find enough space within the complex for all these new courts. Even by late June, the league office still hadn’t finished scheming the logistics, and the first teams were scheduled to practice inside the league’s bubble on July 9. “That was, by far and away, one of the biggest infrastructure hurdles we had to overcome,” said Joey Graziano, the NBA’s vice president of event management.

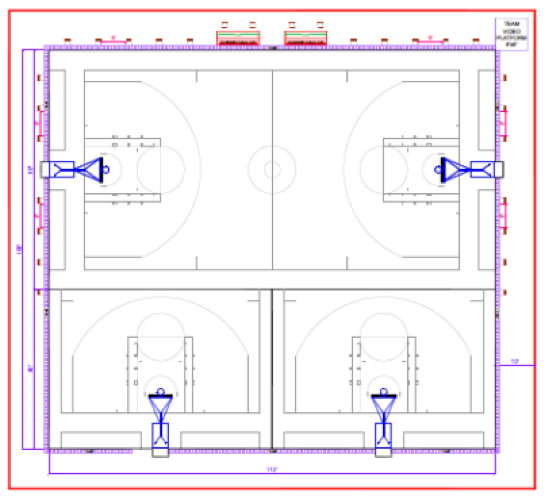

The standard NBA floor is a roughly 120’ x 60’ slab of wood with a 94’ x 50’ court painted on it. Each practice area needed to fit two courts side-by-side inside a 140’ x 140’ space with a minimum 22’ ceiling height. Yet even in massive spaces like the 42,336 square-foot Fantasia Ballroom inside The Contemporary Hotel convention center, the league found sloping ceilings and chandeliers that would make it impossible to fit multiple courts underneath. “That caused a couple nights of heartburn, for sure,” Graziano said.

After considering nearby off-campus locations, the NBA decided to stay within the Disney complex for safety reasons. There was a breakthrough when they figured out they could put the two half-courts alongside a full 50’ x 94’ court, and squeeze a smaller practice area into the Visa Athletic Center along with the third broadcast court. “We were celebrating,” Graziano says.

Next, Graziano’s team scrambled to find hardwood for them. At one point, the league asked its longtime flooring partner, Horner Sports Flooring, if the company could build floors for as many as 12 courts. It takes three weeks to manufacture an NBA court, with the market price currently sitting between $120,000 and $130,000 including freight cost. Eventually, the NBA opted to “borrow” many of the floors in order to save money and time.

Nearby teams the Miami Heat and Orlando Magic each sent two courts -- their home floors plus alternative courts the teams use when wearing their “city” jerseys. The NBA is using the Indiana Pacers’ court while Bankers Life Fieldhouse undergoes renovations, saving the team the cost of storing the panels for the summer.

After all that, the league still needed two more practice courts, two half-courts, and three game courts from Horner. The three “broadcast courts” in the bubble measure 120’ by 68’, 8 inches wider than standard. Even with no courtside seats, this protracted floor puts an additional four feet between the playing surface and the plexiglass that separates scorer’s table, media and broadcast crew members. “To ensure we have physical distancing practices as well,” says Graziano.

It then took a total of 14 trucks to deliver all of the floors to Orlando and 90 hours to assemble them. The league has since compiled an intricate practice schedule for each court that allows each team upwards of five hours daily, opening as early as 8:30 a.m. Those practice spaces are used in three-hour blocks, during which each team gets access to four baskets, a weight room and a training room. The entire facility is then sanitized for the next hour. Every team is also assigned one half court each evening from either 9-11p.m. or 10-12 p.m..

Players first set foot on those elongated broadcast courts in Florida on July 22. “Getting to the scrimmages was a really important step,” Graziano said. And while games resumed seemingly without a hitch—other than rust—players did struggle with a visual sense of the boundaries of the new playing surface. Without courtside seats, painted aprons or photographers positioned on the baselines, several of the NBA’s best had to readjust their peripheral sense of where that two-inch thick endline lays on a sea of hardwood. “The fact they don’t have that visual to align with early on was creating some challenges,” said Horner CEO Doug Hamar. Teams are used to it now.

That extra space also allows the NBA to use a handful of extra robotic cameras. Up to 31 cameras in total will cover the games at Disney, featuring several new angles such as the, “Rail Cam,” which runs up and down the sideline parallel to the court (one of these almost hit Luka Doncic a few days ago; he said it looked like something from “The Matrix”). “Capturing that courtside feel,” said Sarah Zuckert, the NBA’s head of Next Gen Telecast.

Five Horner technicians currently reside in the bubble. Each day they evaluate all of the playing surfaces for texture, cleanliness and the lateral and longitudinal fit of the panels. They also confirm each floor’s coefficient of friction is between 0.5 and 0.7.

“Are they too sticky or too slippery?” said Hamar, when reached by phone from the NBA’s campus. He was eagerly awaiting results of that morning’s Coronavirus test, hopefully to be cleared to leave his hotel room. There was wood to inspect.

Originally Appeared on GQ