How the National Gallery hid its art in a Welsh mountain

A few weeks ago – shortly before 6pm on March 18, to be exact – a recorded message echoed through the National Gallery, informing visitors that it would open again the following morning. It didn’t.

It was a very sad moment,” says its director, Gabriele Finaldi, speaking to me via Skype from his book-lined study at home. “To know, that night, that [daily message] wasn’t true, that the gallery as a resource for people – a place where they could enjoy talking about pictures in front of them – was going to stop for a while: it was heartrending.”

Even during the Second World War, Finaldi continues, when the collection was sent for safekeeping to a cavernous quarry in a Welsh mountain, the gallery remained open. “Now, though, the doors are closed, the lights are off, and no one’s going into the building. So, you could say this is unprecedented.”

To cap it all, Finaldi, himself, was laid low by coronavirus – though he has mostly recovered, and is intent on remaining positive. “So, while the gallery’s doors are shut in Trafalgar Square,” he tells me, “we very much think of our doors being open online.” Last week, his team announced an impressive new digital programme, including curators’ talks, filmed inside their living rooms, and online tutorials on “slow looking”, designed to bring the National Gallery’s pictures into “the nation’s homes”. “The gallery continues to be a cultural presence,” Finaldi says. “We’re still producing things that, we’re confident, people will want to see.”

It’s revealing that, when casting around for a comparably difficult period in the gallery’s history, Finaldi invokes the Second World War. These days we’re hearing a lot about Britain’s wartime experience. Politicians and commentators summon memories of the “Blitz spirit”. The crisis, we’re told, is Boris Johnson’s opportunity to emulate his hero, Winston Churchill. And, it turns out, the National Gallery’s new digital programme was explicitly inspired by its wartime history.

At the start of the conflict, its director at the time, Kenneth Clark, swiftly put together a rousing programme of musical concerts and exhibitions that, together, offer a fine example of the way art, in the broadest sense, can provide people with hope during dark, turbulent times. According to Finaldi, the war years are “a source of inspiration not only for us at the National Gallery, but also more widely, throughout the museum community.”

The history of those years is told brilliantly by Suzanne Bosman in her recently reprinted book, The National Gallery in Wartime. In it, she relates how, after war broke out, Churchill nixed plans to evacuate the gallery’s treasures by ship to Canada: “Hide them in caves and cellars, but not one picture shall leave this island.”

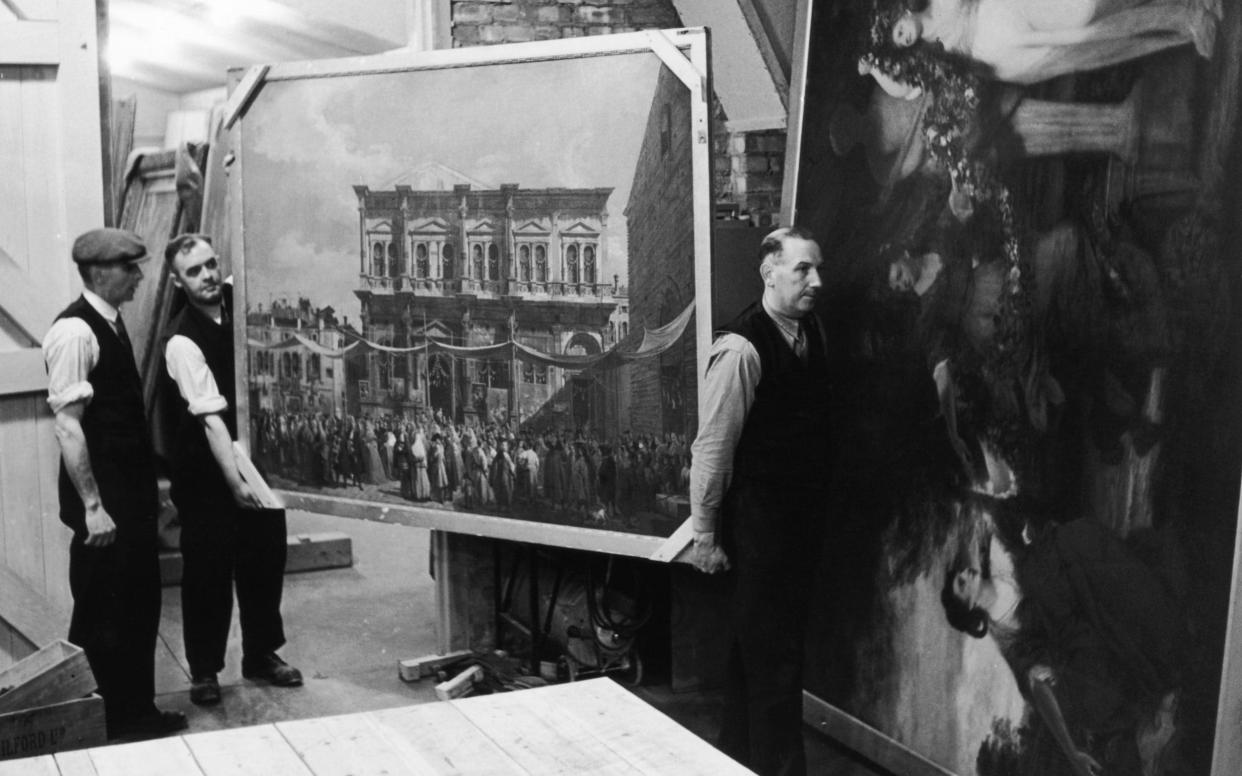

That was fine by Clark, who worried that the Canada plan would expose the gallery’s precious paintings to the risk of torpedo attacks while they voyaged across the Atlantic. Eventually, he sanctioned moving the whole collection – which, shortly before the declaration of war, had been scattered across various, mostly Welsh locations, including castles and stately homes – into bespoke brick “bungalows” erected deep underground in a vast disused slate quarry at Manod, near the mining town of Blaenau Ffestiniog.

As Bosman recounts, the site had several advantages – chiefly, that, at 1,700 feet above sea level, and “only accessible via four miles of winding, mountainous road”, it was remote. At the same time, it was close to a railway, which meant that paintings could be transported to its vicinity with relative ease. Still, getting the collection to Manod was always going to be a logistical challenge, and, in the summer of 1941, a complex operation began. A massive triangular packing crate – nicknamed the “Elephant Case” – transported the largest masterpieces, such as Van Dyck’s Equestrian Portrait of Charles I, which is more than 12ft high. Supposedly, the tyres of the truck carrying it had to be deflated so that the case could pass beneath a low railway bridge near Blaenau Ffestiniog.

After five weeks, everything was in situ, where it remained – mostly unscathed, aside from the occasional minor rock fall, and in carefully controlled conditions of constant humidity and temperature – until the end of the war. Thank goodness, because, during the Blitz, the National Gallery was hit nine times. In 1940, Hampton’s furniture store – on the adjoining plot that is now the site of the gallery’s Sainsbury Wing – was destroyed by incendiary bombs.

With the paintings out of harm’s way, Clark had to decide what to do with the empty gallery, which officials in Whitehall were eyeing up for the war ministry. By chance, as early as September 1939, the renowned concert pianist Myra Hess had offered to perform the occasional concert inside the gallery to boost Londoners’ morale. Clark seized on the idea at once.

“I said she must not give a single concert in the Gallery,” he later recalled. “She must give one every day. She recovered rapidly from the shock, and said it could be done.”

There was trepidation that a highbrow programme of classical music would not appeal to a wide audience, but the first concert, performed beneath the dome of the gallery’s spectacular Barry Rooms that October, was a hit: a black-and-white photograph records the long queues that formed as people waited patiently to hear Hess play. From then until April 1946, when the last weekday lunchtime concert took place, Finaldi says that “nearly 2,000 concerts were given. Hess performed about 150 herself, but she was also responsible for organising all the others, with choirs, small ensembles, larger orchestral groups, and so on.”

According to Bosman, Hess even persuaded “giants” such as Benjamin Britten and Henry Wood to participate. Finaldi smiles. “It’s very, very impressive that there wasn’t a single day when those concerts didn’t happen. They were maintained religiously throughout the war.”

Inspired by their example, Finaldi is currently assessing the feasibility of a programme of concerts performed inside the empty rooms of the National Gallery during lockdown. Watch this space, he tells me: “We do a lot of music at the gallery anyway, a mix of the classical repertory and more modern pieces. And I’ve always thought it was the most natural thing in the world for music and pictures to go together.”

For Hess, overseeing the concerts was a kind of calling: “If I had died the day peace was declared,” she later said, “I would have felt my life’s work was complete.” Gripped by this vocation, she ignored her American agent’s demands to fulfil a lucrative tour of the United States.

Eventually, Clark sent a telegram to shut the agent up: “Understand that you do not quite realise the importance of concerts in the National Gallery by Miss Myra Hess which have been attended by over 10,000 people including the Queen and the Chancellor, and have already become a national institution.”

Hess may be seen performing in the Barry Rooms in front of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, wife of King George VI, in Humphrey Jennings’s classic 1942 film Listen to Britain. For the film, Jennings invited Hess to play Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 17 in G – but the piece with which she was most associated was her own arrangement of Bach’s Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring, with which she often began or ended a concert. The story goes that when a journalist on a train asked a soldier whistling this famous piece of music if he was interested in Bach, he replied: “That’s not Bach. That’s Myra Hess.”

As well as Queen Elizabeth, one of the many people who attended Hess’s concerts was my grandmother, Gwynedd, who is about to celebrate her 99th birthday. In 1942, she was a schoolteacher living with a college friend in a house overlooking the Thames in Barnes, in southwest London: “We inherited a Norwegian housekeeper who had a goose called Juliet,” she recalls. “We did our own cooking, but, from time to time, Juliet’s eggs resulted in a delicious omelette, which was very welcome during rationing.”

Occasionally, when she wasn’t teaching – or exhausted from nightly fire-watching duty – at Haberdashers’ Aske’s School for Girls, then situated in Acton in west London, she would take the no. 9 bus to Trafalgar Square and pay a shilling to listen to one of the lunchtime concerts at the National Gallery. She still remembers the “strangeness” of encountering the gallery’s “empty walls”: “Everything was so secret,” she recalls. “We only got to know years later that the pictures were inside a Welsh mountain.”

She also recollects the “excitement” of “actually hearing Myra Hess” – as well as the fact that the bells of the nearby church of St-Martin-in-the-Fields “sometimes interfered with the music – but the musicians played on.” During one concert (which my granny didn’t witness), an unexploded 1,000-pound time bomb, which had landed elsewhere in the gallery the night before, suddenly blew up. Supposedly, the string quartet playing Beethoven at the time didn’t miss a beat.

As well as the concerts, Clark organised a series of lectures and temporary exhibitions inside the gallery, covering everything from 19th-century French painting and the work of Augustus John to “English Book Illustration Since 1800” and contemporary interior design. In 1941, the art critic Herbert Read described the National Gallery as “a defiant outpost of culture right in the middle of a bombed and shattered metropolis.”

For three weeks in early 1942, Clark also put on display a single, recently acquired portrait, probably by Rembrandt. Since, by then, the Luftwaffe’s nightly bombing raids had abated, this, in turn, inspired the National Gallery’s “Picture of the Month” scheme, which endures today. As Finaldi explains, the idea was that “every month, a single picture should come down from the quarries in north Wales, and be shown to the public in the main entrance to the gallery, behind the portico. At night, it would then be taken down to storage [for safety].”

Titian’s Noli Me Tangere – which I wrote about on Easter Sunday – was the first of more than 40 works exhibited in this manner. “Little by little,” says Finaldi, “quite a few of the gallery’s masterpieces were shown to the public.”

It may seem strange that, despite the threat of bombing, people still gathered to listen to Bach or look at a Bellini. Would a public concert go ahead today if the authorities knew that an unexploded shell lay elsewhere in the same building? For Finaldi, such plucky determination isn’t foolish but “impressive”: “One looks with huge admiration to those times,” he says, “when music and art were considered so important that you would risk your life for them.”

Do they still play such a central role? “Well,” Finaldi replies, “when we’re all sitting in our houses trying to work out what’s happening around us, certain things come to the fore. We cling to culture as a mark of our identity, of civilisation. A collection like the National Gallery’s says something about who we are. At a time like this, it becomes even more important than before.”

Isn’t it curious, though, that paintings can have such an effect? “I agree, it’s a paradoxical thing that a few splashes of paint on a piece of wood or canvas can be invested with such meaning and importance,” he replies. “But I suppose, as a society, we deposit in these objects – whether paintings and sculptures or pieces of music or great films and works of literature – what we consider most revealing, most truthful, most valuable about our nature. And these things give people a lot of solace and comfort.”

Information: nationalgallery.org.uk