How Nancy Cunard—And Her Trademark Bangles—Inspired an Iconic Brancusi Bronze

U614559INP

Was she wearing her trademark bangles, stacked from wrist to elbow, the night Nancy Cunard met the sculptor Constantin Brancusi?

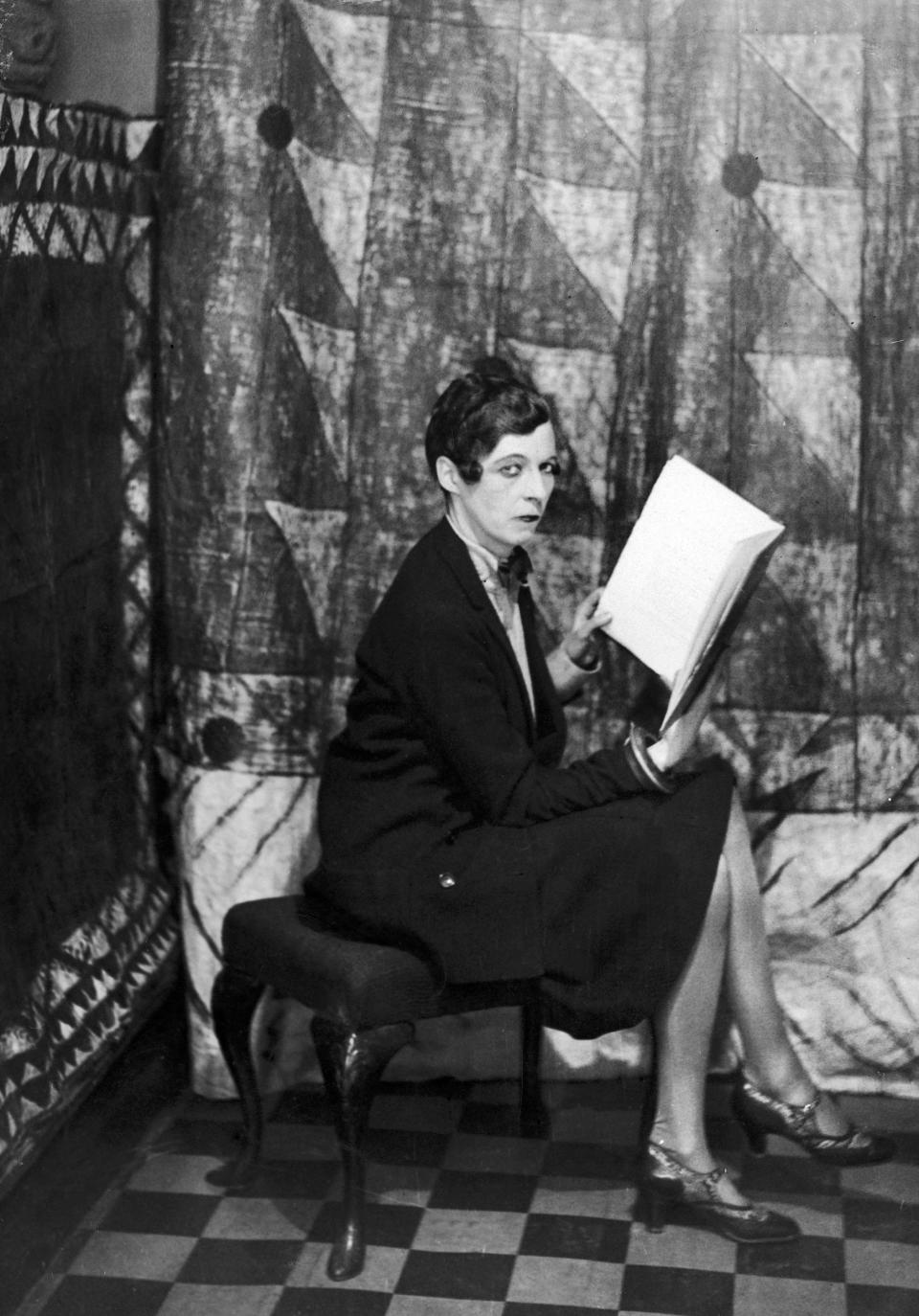

Cunard, a poet and publisher, an heiress and an activist, a muse and a journalist, was renowned for her wild elegance. Tall and whippet thin, her hair shorn in the La Garçonne style of the Jazz Age, she had, according to contemporaries, a face “like Nefertiti,” skin as “white as bleached almonds,” and large eyes as blue “as sapphires.” Decades before it became accepted, she embraced African jewelry, a style that at the time was described as “barbaric.”

She never posed for Brancusi, but her strange beauty clearly captured his imagination. “Everything about the way she behaved,” he once said, “showed how truly sophisticated she was for her day.” In 1932, he cast the stunning polished bronze sculpture La Jeune Fille Sophistiquée (Portrait de Nancy Cunard), for sale tomorrow at Christie’s, the first time it has become available since the original owners purchased it from the artist in the 1950s. The estimate for this rare work is $70 million—but in fact, one could argue that this modernist masterpiece and the woman it portrays are ageless and priceless.

Cunard was born to an English aristocrat and an American socialite mother in 1896. When she was a young woman, she hung out with Iris Tree and other scions from families of great privilege—they called themselves the “Corrupt Coterie.” She loved to party: One late London night, she and Tree were discovered swimming in the Serpentine, emerging at dawn, Cunard recalled, “drenched in homemade outfits of velvet, chiffon, ribbons, feathers, spangles, and artificial flowers.”

She was not just sowing youthful wild oats—all her life, she remained true to a deeply personal bohemian code. She had affairs with Tristan Tzara, Ezra Pound, Samuel Beckett, and Louis Aragon. Man Ray and Cecil Beaton photographed her; Oskar Kokoschka painted her. In 1928, she took up with an African-American jazz musician named Henry Crowder. (On hearing this, her mother reportedly said, “Is it true that my daughter knows a negro?”)

K038101-A4

Cunard had her own publishing house and sought out avant-garde writers; she championed civil rights and was an avowed anti-fascist. In 1937, she helped circulate a questionnaire to 200 or so writers that asked the following question: “Are you for, or against, the legal government and people of Republican Spain? Are you for, or against, Franco and Fascism?” There were 147 answers, of which 126 supported the Republic. (The most famous response came from George Orwell and began: “Will you please stop sending me this bloody rubbish.”)

No one ever said she was easy, but she stuck to her principles, and she was invariably on the right side of history. If today she is most often remembered for her uncompromising gaze and those bracelet-laden arms, we might also take a moment to honor her fierce individuality—so riveting, so splendid that no less an artist than Brancusi sought to capture it with a twist of mere metal.