The Mustache Is Thriving. But What Does It Mean?

As a kid raised in Canada in the 1980s, all my heroes had mustaches. Lanny McDonald, Wendel Clark, Jamie Macoun—the mustache was as prevalent as the maple leaf on their (yes, ice hockey) jerseys. And there was Larry Bird. And Magnum P.I. My uncle had one. Lots of dads had them. But then—aside from an aughts hipster blip—they became a rarity. What happened?

“Like all facial hair, the mustache is cyclical,” says Dr. Allan Peterkin, author of One Thousand Mustaches: a Cultural History of the Mo. During periods of unpopularity, Dr. Peterkin says, the mustache has been associated with three Fs: fiends, fops and foreigners. This is among white Westerners, mind you; he stresses that the same mustache fads and standards have not often applied in Black communities.

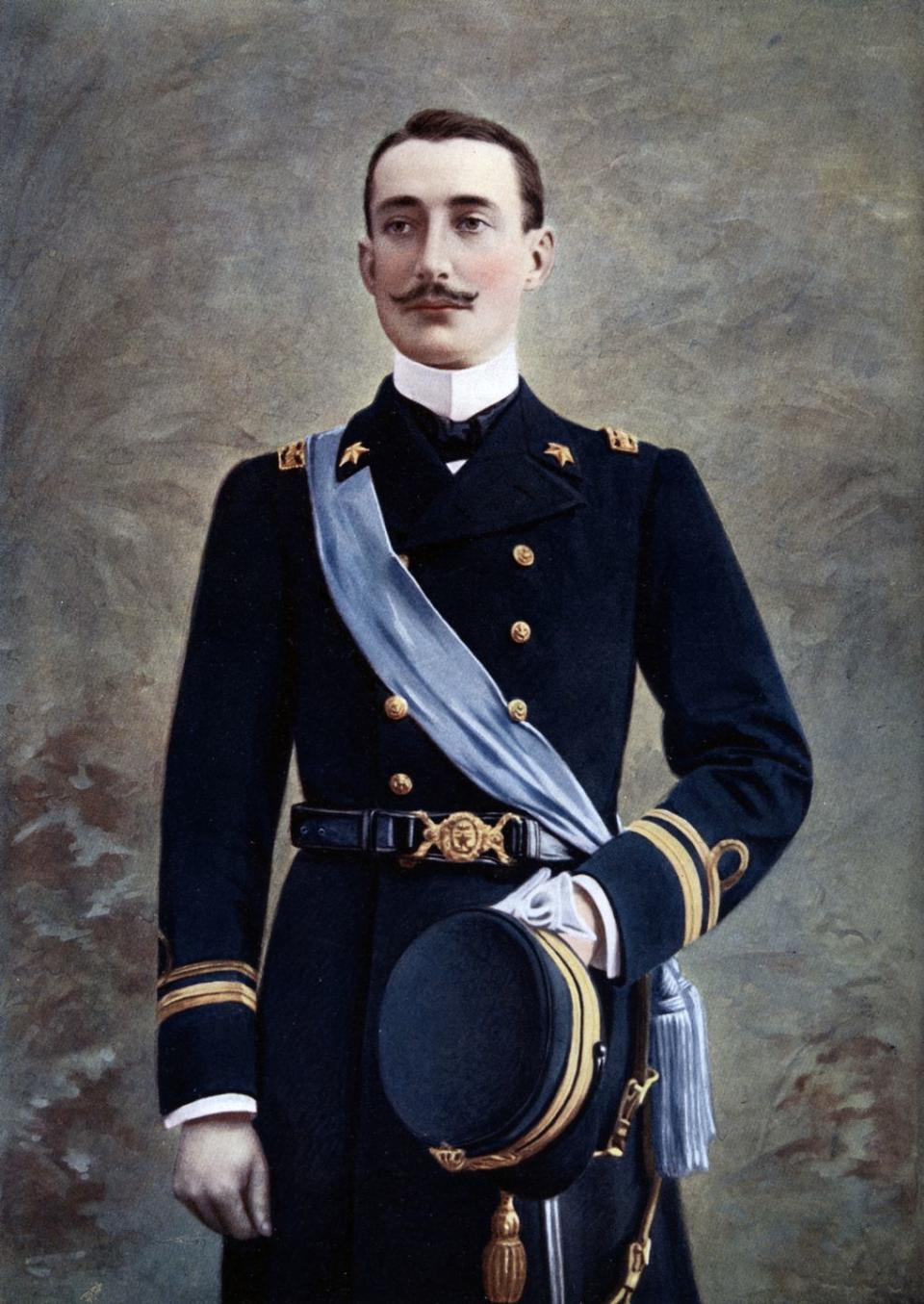

Throughout their history, men and their mustaches have often met over masculinity, or the loss thereof. It’s why mustaches raged in with the modern age: Industrialization, it seems, struck some as quite emasculating. “For Victorian men, their role is out among nature, master of their domains,” says Dr. Alun Whitey, another facial hair expert and lecturer in history at the University of Exeter. “Suddenly, they’re working under bosses in offices and factories.” At the same time, soldiers were coming back from the Crimean war sporting mustaches, which were associated with particular regiments, and it became a popular expression of extreme masculinity (alongside many bogus health claims, like that they’d keep disease from getting up your nose).

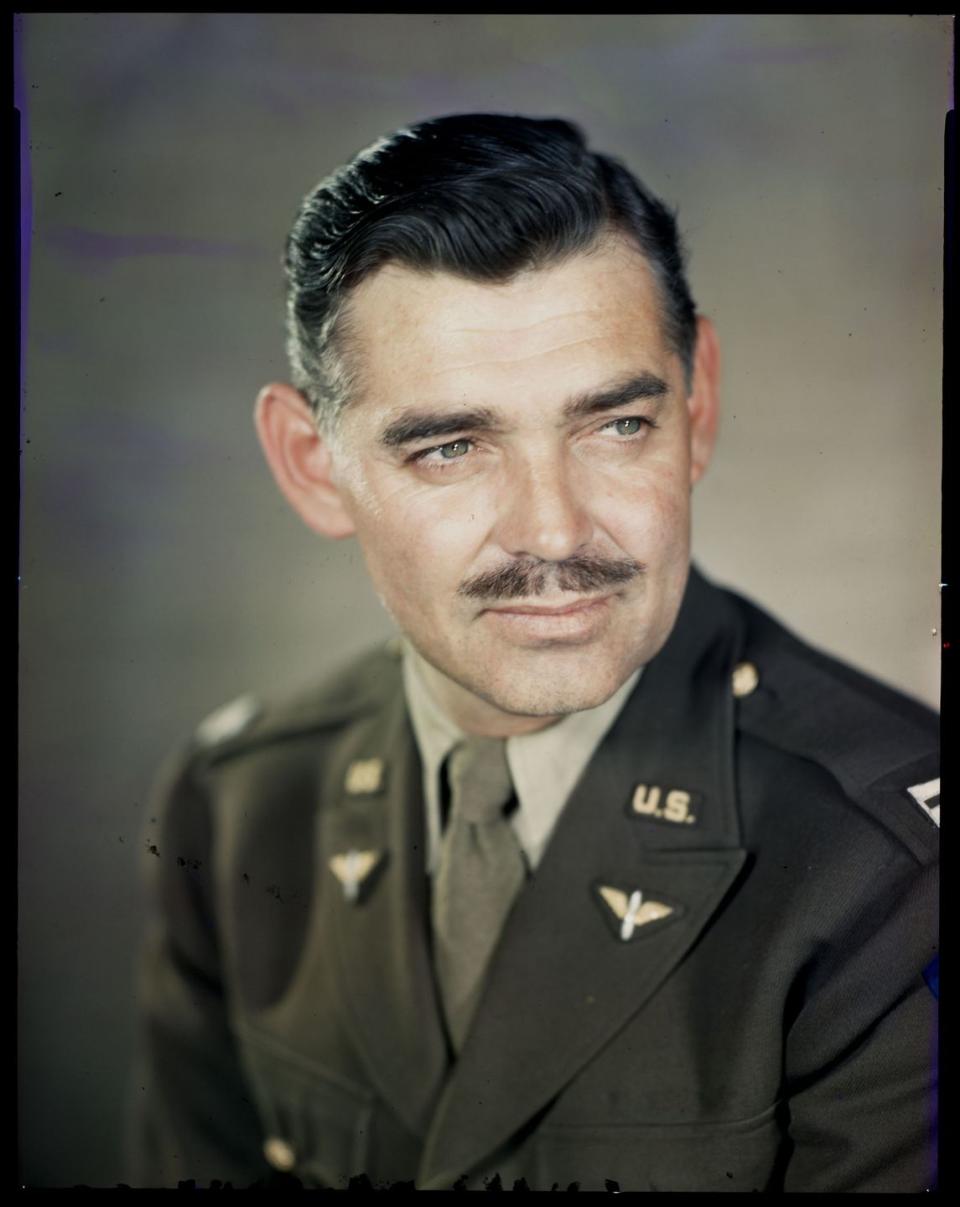

This goes on. Presidents from Grant (elected in 1869) to Taft (who departed in 1914) sported the ‘stache, including Grover Cleveland (both times). At the outbreak of World War I, to enlist in the British Army you had to have a mustache, says Dr. Whitey. And if you couldn’t grow a mustache, they’d give you one (made of goat hair). There’s some back-and-forth in the ‘20s and ‘30s. Leading men like Clark Gable sported well-kept little numbers. Meanwhile, you couldn’t work for Disney if you had a ‘stache, even though Walt himself famously had one. And then a very famous mustachioed German made the whole enterprise rather unattractive for a good while. Then came the ‘60s.

Suddenly, hair was political anew. And as cool took over and the counterculture became mainstream, those politics got complex. Rock became pop, uptown started to meet downtown, and as the free-love ‘60s gave way to the key-party ‘70s, former hippies graduated law school and moved to the suburbs. The hair heads got trimmed, or simply said adieu. A mustache became a way to assert one’s free past, but also to fit in. It became both a symbol of an older-school, tough-guy virility (see Burt Reynolds and Charles Bronson) as well as refined way to express new sensitivities and creative personas (Sonny Bono and Stan Lee). At the same time, it became the aesthetic of the average Joe, mutating from the look of a “foreigner” who back in the day might have pushed bolshevism in imagined bars and back alleys to one of the American working man. (This stuck around. Think of the only working-class person we ever met on Friends; it was their mustachioed super).

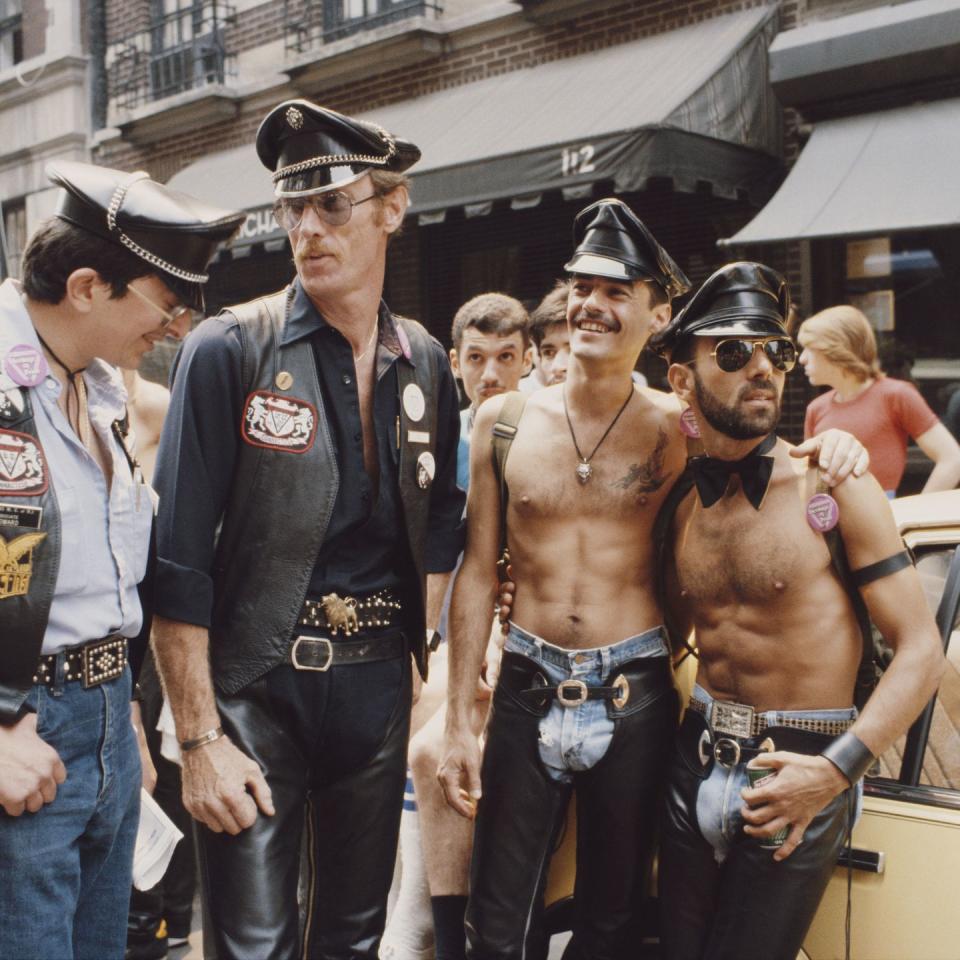

In the latter third of the 20th century, that coding got ever more nuanced as we looked west, to the Castro in San Francisco. As gay identity and politics began to penetrate pop culture, we saw the emergence of the Castro Clone, often wearing a heavy mustache: a reference to the working Joe. The aesthetic spread throughout the country. Simultaneously, the adult film industry added to the notion of the hypersexuality of the hairy-lipped man (yep, we’re talking about the fabled “porn ‘stache”).

So on one hand the mustache was aligned with the status quo (think firemen and cops), while on the other it became shorthand (and occasionally handlebar) for the sexual outsider: the swinger, the porn star, the gay man. In both cases, it can be seen as a unifier: “There’s always been a fireman mustache, policeman mustache,” says Dr. Peterkin.“That’s an expression of solidarity, of male bonding, an identifier of what you do.”

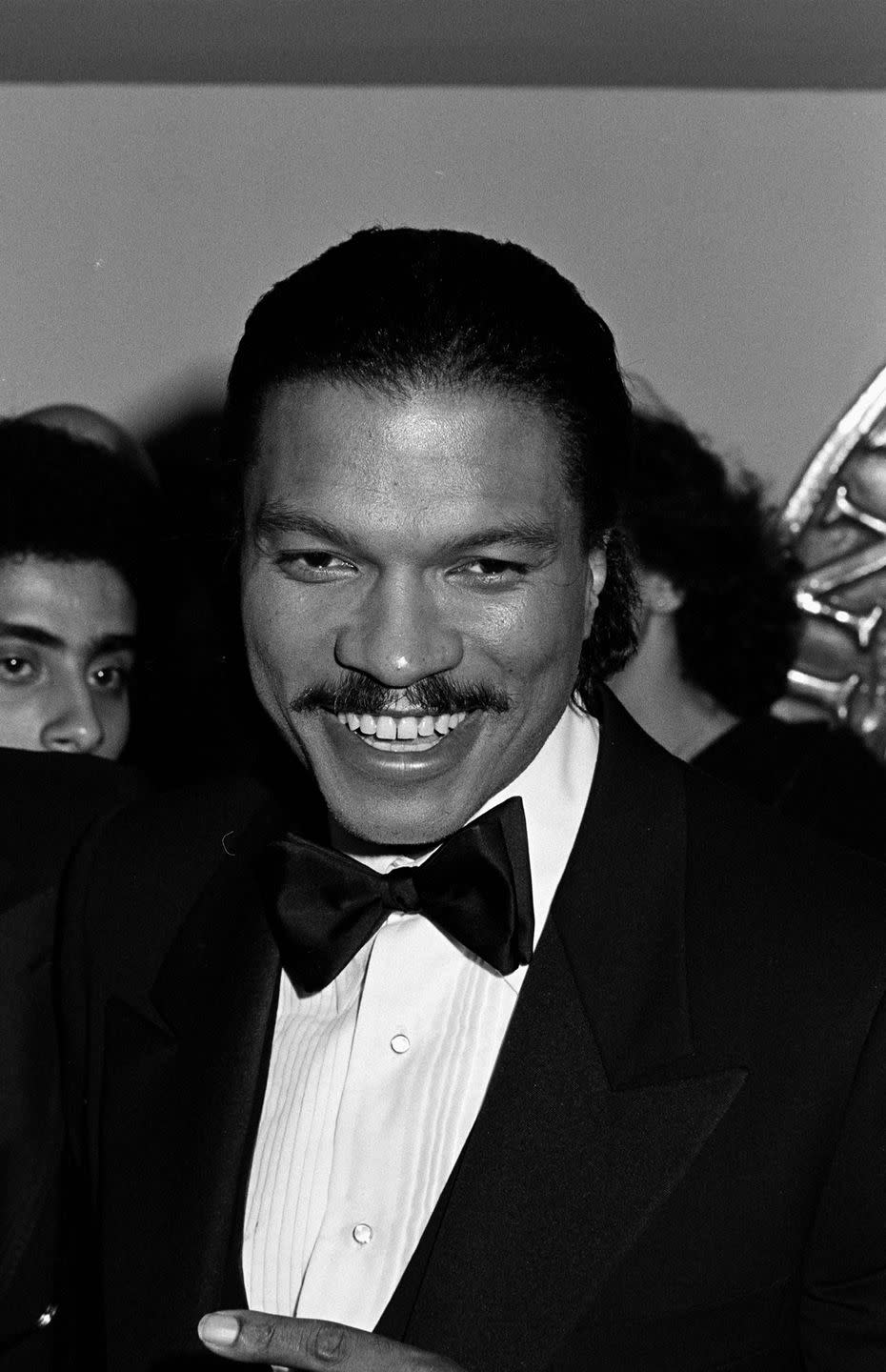

It also became the provenance of certain class of high-flying heroes, from Larry Bird to Lando Calrissian, who exists at an interesting place at the intersection of alien and (by Billy Dee William’s own declaration) Armenian. Depending on when George Lucas’s camera catches him, he’s at once a fiend, fop (that cape!), and a foreigner. But generally speaking, in modern American history, the mustache has been a consistency, not a telegraph of any mode of temporal identity, for Black men.

“It’s been persistent in that it doesn’t vanish for long periods. And it stays on the faces of public figures,” says Dr, Peterkin, pointing at a modern timeline of mustachioed Black men, from Martin Luther King Jr. to former Attorney General Eric Holder, to clergymen, to actors, from Carl Weathers to Michael B. Jordan. “It was common enough that it could be viewed as a grooming expression of Black men,” he says. “It’s not making additional statements of possible identity the way it is for white men.” (Facial hair grooming—and in fact all barbering in the USA—has profoundly racist roots that go back pre-revolutionary days and slavery, as denoted in Sean Trainor’s “The Racially Fraught History of the American Beard” in The Atlantic.)

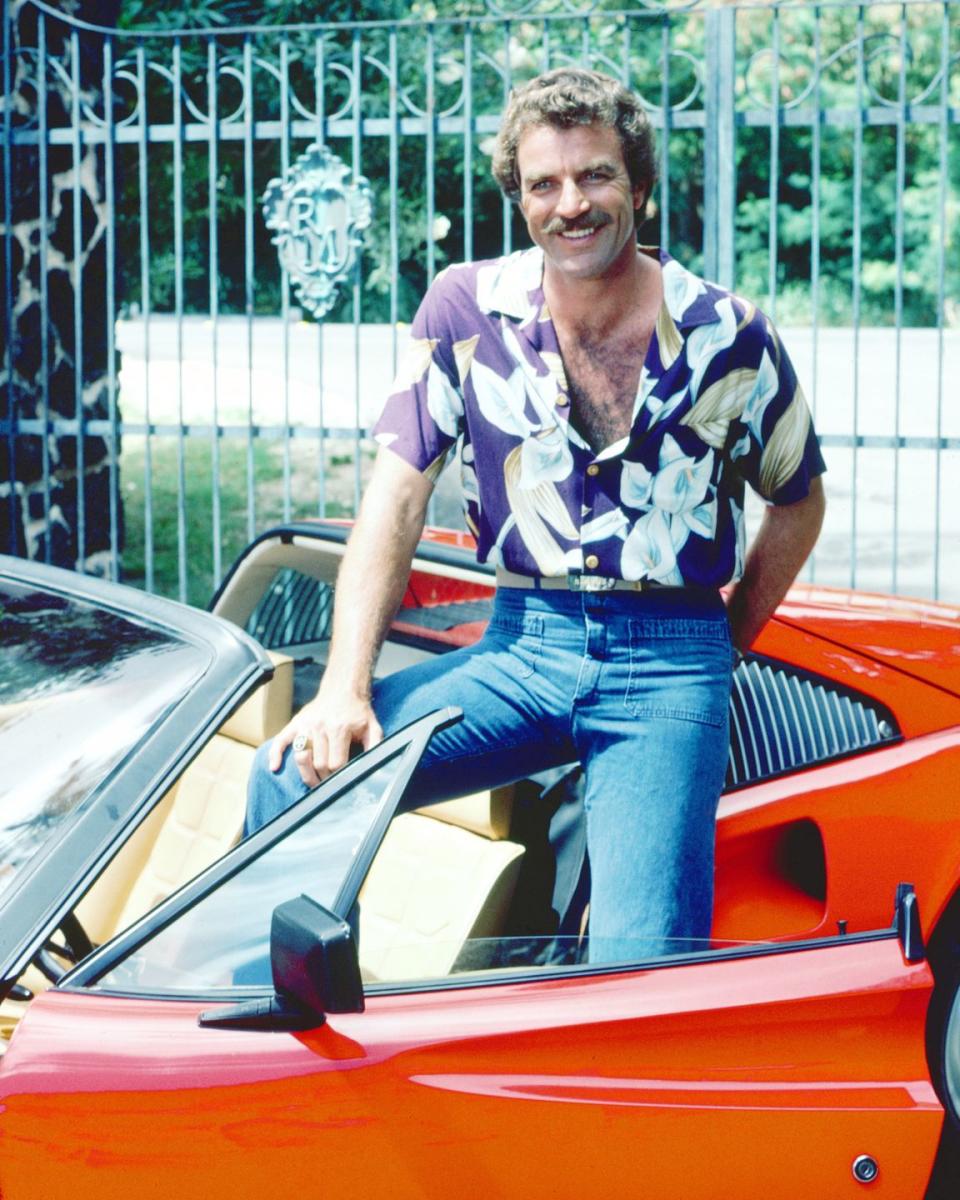

At the same time as Star Wars, there was Magnum, P.I., the influence of which cannot be overstated. Tom Selleck’s manly beauty caused reverberations that far outlasted the show’s run, and even imbued later figures sporting stronger ‘staches with a sex appeal that otherwise might speak only to the avuncular. The Alex Trebek, if you will. This dominant, knowing mustache says not only one thing, but is unified in a single voice: Daddy’s.

Alas, the ‘stache doesn’t really have a moment again until the hipsters bring it back in the mid aughts. The late ‘80s saw it as the property of abusive husbands (Sleeping with the Enemy), or perhaps half of an iconic rock duo. The ‘90s were mostly clean-cut (Brandon and Dylan could play with those perfect bar graphs next to their ears, but mustaches weren’t happening), with the end of the decade giving way to the goatee, often stylized within an inch of its life a la Backstreet Boys.

The interesting thing about the mustache’s return with early-aughts hipsters is that it came with healthy doses of irony. Following the “metrosexual” boom, the hipsters’ efforts—from overalls to trucker hats to tonsorial expressions—tended to reference a history. “Young guys are playing with being macho but they’re not really macho; there’s a wink of the eye,” says Dr. Peterkin. More than a decade later, as that generation moves into management and ownership positions, the result is a more open world, in terms of the facial hair we can sport. “Men are freer now,” he says. “They don’t have to worry about not getting hired [because of facial hair]. Young men don’t care if you read their mustache as being sexual.”

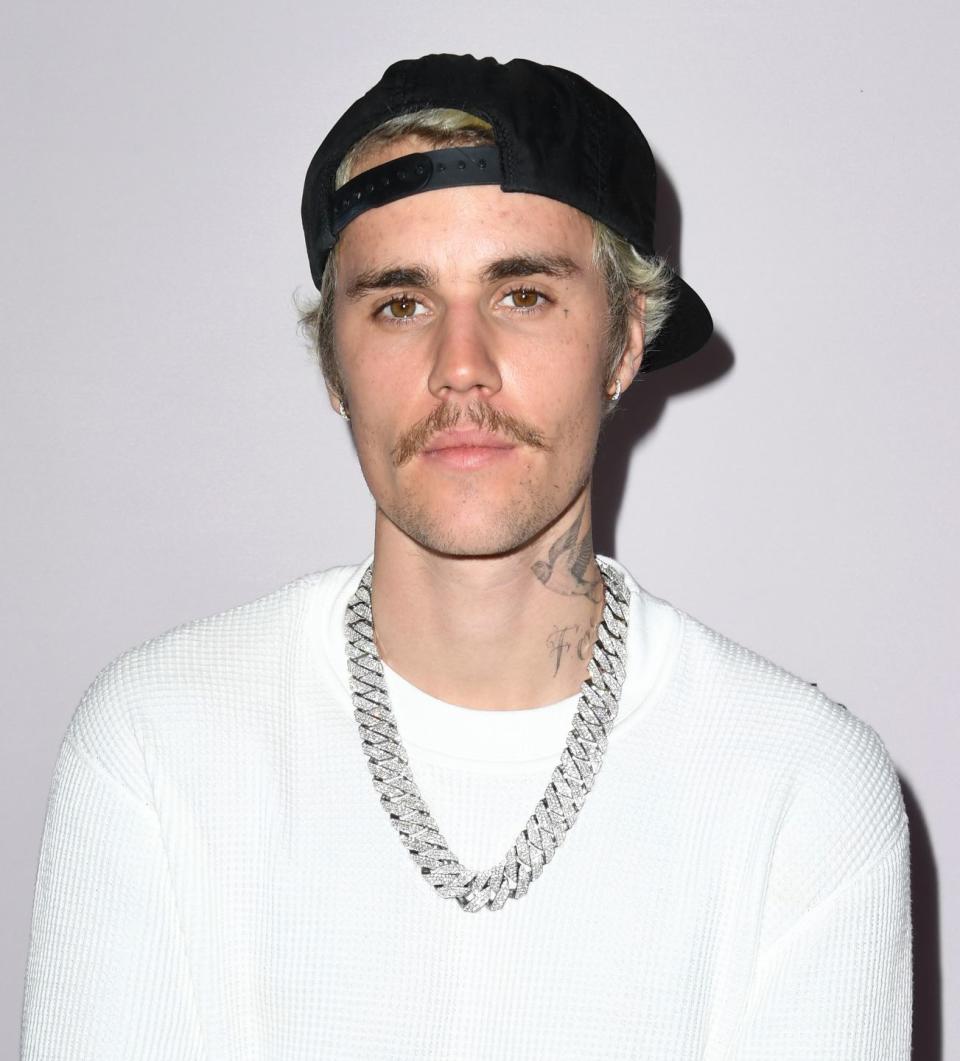

Which helps us understand so much about where the mustache is, and isn’t, now. We’re in an age where the most popular musician in the world, one of our great sex symbols, rocks a mustache, or at least a socially distanced assembly of hairs pretending to be one. He has towered, on his Calvin Klein billboard, over Lafayette and Houston in NYC, wearing nearly nothing. And at the same time, he’s big into Christ and choreographed dancing and recently spoke publicly about the awkwardness of sex.

What’s interesting is that none of these details much matter any more. It’s less that the mustache itself has been defanged than its wearer. Facial hair experts argue that the mustache reappears at times when masculinity is under threat. But what happens when masculinity is in a process of being redefined, as is gender?

Today’s mustache might be caught in circles of irony that bite and play with centuries of attempted manliness, but at the same time it’s escaping the bristling tyranny that inspired it for so long. Contemporary masculinity has been redefined in so many ways, with far-reaching implications. One of them is that nowadays, your mustache gets to be less of a signpost, and more of a mustache, than ever.

You Might Also Like