Must Knit Dogs: Meet the People Who Turn Stray Pet Hair Into Sweaters

A few months ago, as summer was turning to fall, my dog Chester began to shed profusely. He’s a fluffy mutt, part-Australian shepherd (I think), and emits a cloud of hair all the time—but twice a year, he “blows his coat.” For a few weeks, I was brushing him everyday. Hair coated my couch, my clothes, and filled my garbage can. Tumbleweeds of it blew around the apartment when I turned on the overhead fan.

As I walked Chester each night, he never seemed to mind the dropping temperature, while I was shivering in the cold. Accordingly, I’d become obsessed with buying a fuzzy sweater and had been scouring eBay for vintage Angora and mohair. Perhaps it was a sign that I had truly fallen into dog-dad madness, but I found myself wondering if, instead of throwing it all away, I could somehow put Chester’s hair to use. What if I could make a Shaggy Dog sweater out of my own shaggy dog?

Thus began my descent into the world of people who spin and knit clothing out of dog hair.

My first step was some cursory googling. What I found was that in America, two women are credited with popularizing the idea of spinning and knitting with dog hair: Kendall Crolius and Anne Montgomery. Their book, Knitting With Dog Hair: A Woof to Warp Guide to Making Hats, Sweaters, Mittens, and More was published by St. Martin’s press in 1994, and has developed a cult following. It includes a step-by-step guide of how to gather, spin, and knit a dog hair garment, and even comes with dozens of patterns, including two sweaters with dogs on them (made of dog!). But more than providing the necessary instructions for would-be DIYers, the book brought to light what had previously been an obscure practice and helped spread the gospel of chiengora. (“Chien” is French for dog, and “gora” comes from Angora, a soft rabbit hair.)

In their introduction, Crolius and Montgomery even predict that dog hair spinning and knitting will become “the new national craze” and “the craft of the nineties” because of the low ecological footprint of using pet hair instead of raising sheep for wool. Unfortunately, they were a little ahead of their time: chiengora didn’t blow up along with cargo shorts and bucket hats, but today you can find hundreds of dog hair knitters and spinners online, many of whom are embracing the sustainability of the practice. In the intervening twenty-five years, what was once an eccentric hobby has become a kind of craft subculture, with pet owners around the country swapping tips, meeting up, and even turning their projects into small businesses for less handy pet-owners.

This was how I found Jeannie Sanke, owner and proprietor of Knit Your Dog. A former ad salesperson with a PhD in German literature, Sanke describes herself as “an old woman with a dog, a cat, and spinning wheel.”

She runs her knitting business out of her apartment in Evanston, IL, and when we spoke via FaceTime, the Chicago area was in the midst of a polar vortex. To keep warm, Sanke was wearing a plush, black beanie. It had a halo of fuzz, and a glossiness I rarely find in merino.

“My dog Shadow,” she said, pointing to the hat. “He was a black Chow.”

I could see boxes piled high behind her. She explained that they were filled with ziplock bags, each stuffed with dog hair sent by people from all over the world. Other bags were chilling in a large freezer chest to kill off any parasites. On a commission basis, Sanke spins and knits this hair into custom garments. She gets so many requests that her waitlist currently stretches back “about two years.”

Sanke walked me through the process of making the dog yarn, which is essentially the same as how normal wool is produced: First, the hair is “harvested”: in other words, you brush your dog. Here, Sanke was adamant that you not use a furminator or any kind of shearing device because it will break the hair fibers and make them prickly. For a soft sweater, you have to brush the old fashioned way, which meant all of the fur I’d so far collected from Chester would be worthless. And here again, Sanke corrected me on terminology.

“Fur is still attached to the skin, and there is a federal ban on that,” she said. What Sanke works with is dog hair. (Also, New Jersey has a ban on dog and cat hair--so no stunting in a doggo sweater outside Satriale’s.)

“The problem is that dog breeds vary so much,” Sanke said, “so not all dog hair works well for spinning. Double-coated dogs do better because the undercoat is the best. That said, I have worked with some poodles that have been let out to grow. Yorkie can spin beautifully. I’ve done a couple of orders with some American Eskimo dog—looks like a Samoyed that’s been left in a dryer.”

Once the hair is collected, she explained that it must be washed; otherwise, your sweater will smell like a dog. Then the fibers are carded with two combs to align them and make them easier to form into yarn—and finally, they’re spun on a wheel or drop spindle. Before you grab your dog and start designing your dream knitwear (I’m thinking Marni meets the American Kennel Club), you should know that it takes about 1,500 yards of spun yarn to knit a medium-sized sweater. Depending on the dog breed, that can take months, or even years, to gather. Plus, the hair should be at least two inches long, ideally three. You can mix dog hair with wool, and if your dog has a short coat, you will have no choice but to mix in a longer fiber—but Sanke and most of her clients often keep their chiengora pure.

This preference for pure chiengora may be supported by science. According to a 2007 report commissioned by The American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists, dog hair is structurally superior to sheep wool (the most popular animal fiber) in most measurable ways. After analyzing their results, the authors concluded that for textile purposes, “dog fibers would perform as well as traditionally-used animal fibers, and possibly better in certain instances.” And anecdotal stories provided by dog hair spinners have long suggested that dog hair is warmer than wool—so warm, in fact, that it can be difficult to wear in temperatures above freezing.

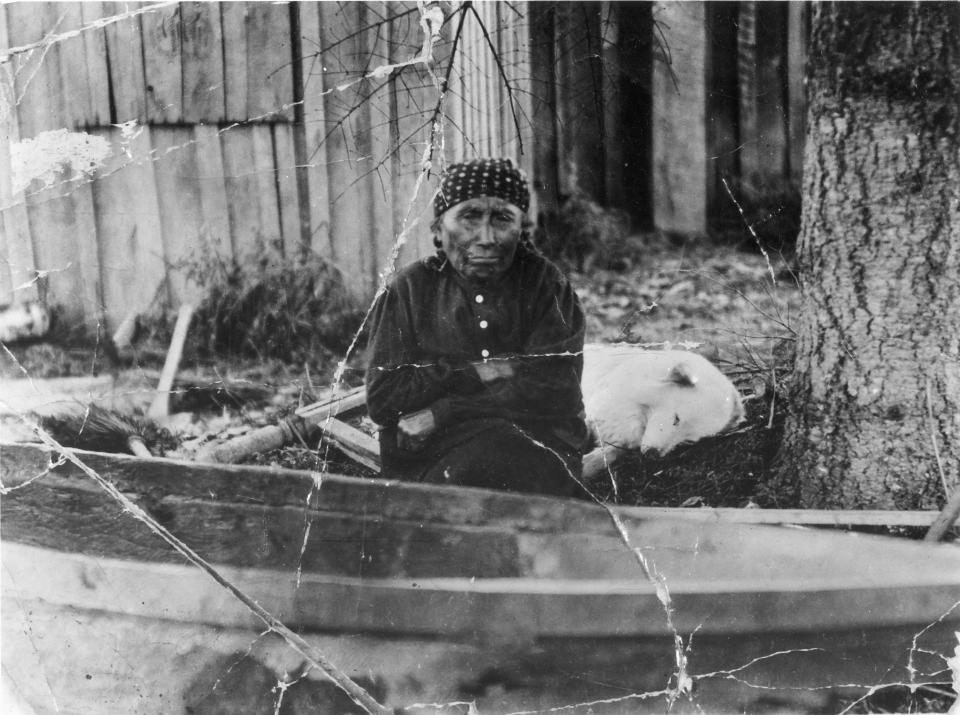

Given all the supposed benefits of dog hair over other animal fibers, I was surprised people hadn’t figured this out earlier. But it appears some people had already discovered how awesome dog hair is: for centuries, the Salish tribes of the Pacific Northwest raised a special breed of dogs for their hair. Known as Salish Woolly Dogs, these fluffy white canines were often sequestered on small islands in the Puget Sound. The first written observations of the woolly dogs were made in 1792 by Capt. George Vancouver at the south end of Bainbridge Island. He described the dogs as “all shorn as close to the skin as sheep” with hair that could be “lifted up by the corner without causing any separation” and was “capable of being spun into yarn.” The Salish people fed the dogs salmon and bone marrow to keep their coats shiny, and collected their hair on a seasonal basis to weave into blankets and other textiles.

These dog hair garments were not only prized for their warmth and soft texture, but were also imbued with cultural significance as a frequent gift at potlatches. When white settlers displaced the Salish people and upended their way of life, they also brought inexpensive sheep wool blankets from England—which undermined the purpose of the special dogs to begin with. Today, if you want to cop some jawnz made of Salish woolly dog, you’re out of luck. The breed has been extinct since the turn of the 20th century, but a few examples of its hair remain preserved in rare blankets, like this one at the Burke Museum in Seattle.

Not surprisingly, preservation—rather than functionality—is the same reason most people want to knit something out of dog hair today. According to Sanke, about half of her clients are people who have recently lost a pet, and who only decide to knit something from their hair once they’re gone. “So many people contact us right after their dog has died.” Sanke understands their motivations, describing her own attachment to a roll of yarn made from deceased dog’s hair. “I do periodically take their skeins out, and just hold ‘em,” she said.

As we finished our interview, I looked down at Chester, who was curled by my feet. It was impossible for me to imagine him gone from that spot in my office one day, and stranger still to imagine transforming his remaining hair into a marled ball of yarn. In that moment, I began to have my doubts about the dog sweater project. It all started to feel a little morbid—not quite taxidermy, but on the same spectrum of creepy acts of preservation committed by overzealous pet lovers who can’t let go.

On the other hand, I reasoned that a chiengora sweater would be the ultimate monument to Chester’s fuzziness. Way better than an oil painting, or the thousands of photographs of him that clog my iCloud storage. As I gave him a pat and picked some stray tufts of hair off his rump, I considered a time when Chester would no longer be alive. My wife likes to remind me that it’s pointless to ponder this eventuality, since her “baby will live forever.” Still, I tried to picture myself wearing a sweater made of traces of my beloved companion in the (distant) future. He stared at me inquiringly with his big, brown eyes. Maybe I should save a few clumps, I decided, pulling another loose hair from my dog. Just in case.

Originally Appeared on GQ