Movie treasures and the rise of Hollywood: inside LA's newest museum

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has a glorious treasure trove of films, scripts, photos, home movies and memorabilia dating back to the early days of Hollywood, but never built a home for it — until now, and the creation of the first Academy Museum.

Forget, for a moment, the glamour (but don't worry, there is plenty to come).

The thing most people associate with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is the Oscars — the most glittering, star-studded event in the world of cinema. But that was later.

In 1926, Louis B Mayer, the most brilliant and ruthless of all the early movie titans, conceived the idea of an industry body to combat the twin problems of organised labour and the unfortunate image peddled by gossip magazines of Hollywood and the nascent movie business as a den of sexual scandal and drug use.

The following year, Mayer organised a banquet at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles for the most powerful figures in Hollywood, to inaugurate his new Academy, which would be open to actors, directors, writers, technicians and producers. The new organisation duly elected its first president, Douglas Fairbanks — a star who, at that time, glowed with the combined wattage of Pitt, Clooney and DiCaprio.

In an act of unusual foresight for the time, the Academy laid plans for an archive and library that would one day constitute a museum of the movie industry. Books, periodicals and documents were collected — and stored away — in a closet at the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood, where the Academy established its first office, and where its first awards ceremony was held, in May 1929.

Hosted by Fairbanks, the event was attended by just 270 people and the presentation ceremony lasted all of 15 minutes. (In recent years, the Oscars show has had around 3,500 attendees and run for more than four hours; although, in a commendable step towards brevity, this year's awards lasted a little over three.)

The collection of books and periodicals grew to include scripts, letters, films, photographs and artefacts. It is now so extensive that it's housed in two locations in Hollywood: the Fairbanks Center for Motion Picture Study and the Pickford Center for Motion Picture Study, the latter named for silent-movie star Mary Pickford, the wife of Douglas Fairbanks and a founding member of the Academy. But the museum was never built.

"For 90 years, they talked about it," Dawn Hudson, the CEO of the Academy, told me. "They had various committees, they hired architects, but there was never the right place, never the right time, never the money..."

Until now. Rising up on a site in LA's 'Museum Row', and scheduled to open next year, is the first Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, dedicated to every aspect of Hollywood history, from the stars, directors and screenwriters to costume, production design and technology.

When Hudson, who previously produced the Los Angeles Film Festival, became CEO in 2011, she says her first priority was to push for the creation of the museum. "We needed to build a museum for our culture, because if the Academy of Motion Pictures is not going to build the premier museum of the movies, who is?"

Hudson approached the board of governors and asked for one year and $5 million to secure the lease on the historic May Company department-store building on Wilshire Boulevard, and to explore the movie industry's commitment to the project.

She sought to raise $100 million in pledges in 12 months. In October 2012, five minutes before the deciding board meeting, her team locked in the final pledge to reach the target.

With the seed money in place, a fundraising campaign was launched, headed by the new museum's chairman, Bob Igur (the chair and CEO of Disney), and co-chairs Annette Bening and Tom Hanks, to raise about $400 million to complete the project.

Designed by Renzo Piano, the museum incorporates a re-envisioning of the May Company building — a celebrated example of the Streamline Moderne style — adjoined to a soaring 130ft concrete and glass sphere.

The six-storey edifice, renamed the Saban Building in honour of a $50 million gift from philanthropists Cheryl and Haim Saban, will feature 50,000sq ft of exhibition space, a 288-seat theatre and the Shirley Temple Education Studio, endowed by the Temple family.

The spherical building will accommodate the 1,000-seat David Geffen Theater, big enough for a 60-piece orchestra, where films from the Academy's huge archive going back to the silent era can be shown in their original form. (The projection booth has been configured to meet the rigorous safety standards required to show movies shot on highly flammable nitrate film — once the standard film stock, it was phased out in the late 1940s.)

A terrace at the top of the globe will offer unparalleled views of the Hollywood Hills — and the famous Hollywood sign. On the day I visited, a pall of smoke from the autumn fires could be seen in the distance.

The Fairbanks Center for Motion Picture Study is located in a handsome 1920s Moorish-style building originally built as a water-treatment centre. In 1991, it was repurposed to house the Margaret Herrick Library.

Herrick was the Academy's first librarian, responsible for laying the foundations of its staggering collection. It was also Herrick, so the story goes, who, looking at the statuette of the Academy Award, remarked "that looks like my Uncle Oscar". And the rest is history.

The library's archive comprises more than 100,000 film scripts, 60,000 sound files, 14 million photographs, 43,000 audio recordings, 40,000 books, more than 100,000 pieces of production art and 1,600 special collections of luminaries such as Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Alfred Hitchcock and John Huston. To browse through the collection is to be transported to the very heart of Hollywood history, legend and myth.

There is a copy of the MGM payroll from 1925, showing that Norma Shearer and Lon Chaney were earning $3,000 week (the equivalent of $44,000 in today's money), a young Swedish actress named Greta Garbo was being paid $400 a week, while a starlet named Lucille LeSueur was on a mere $250.

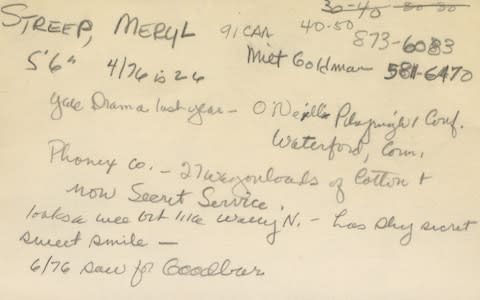

She would soon change her name to Joan Crawford. Audition notes on a young George Clooney observe that he is a "very secure, mature guy — manly", while the then undiscovered Meryl Streep is noted for her "sweet smile".

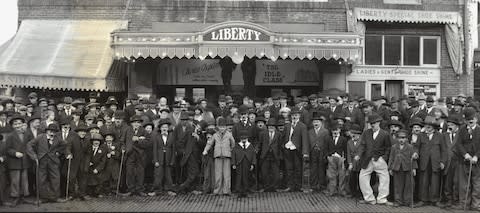

Among the photography collection is a marvellous picture of contestants in a Charlie Chaplin lookalike contest arrayed outside a theatre in New Jersey, in which Chaplin can be spied looking down from an upstairs window. Apparently, he joined the contest — anonymously — and came fourth.

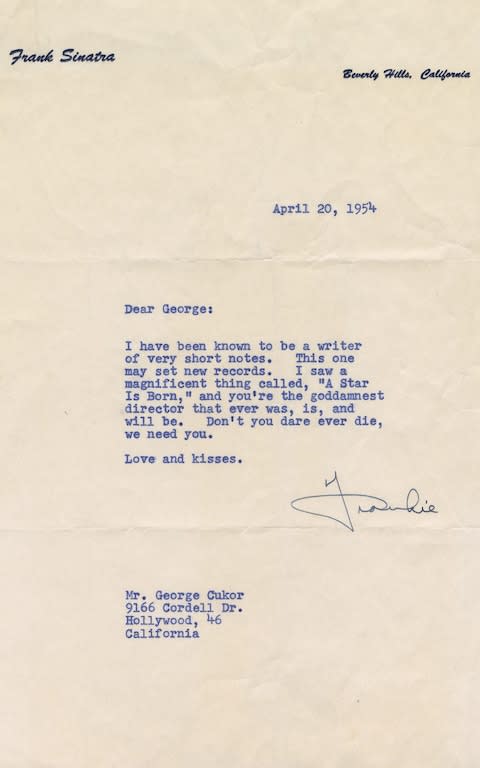

There are production drawings for The Wizard of Oz — and the cowardly lion's mane worn in the film by Bert Lahr — and a trove of correspondence: a letter from Marilyn Monroe in 1960 turning down the offer of a role in a film about Sigmund Freud ("I wouldn't want to be a part of it, first because of his great contribution to humanity, and secondly my personal regard for his work"), and a letter from Frank Sinatra to the director George Cukor, dated 1954, congratulating him on A Star Is Born: "You're the goddamest director that ever was, is, and will be. Don't you dare ever die, we need you. Love and kisses, Frank."

A cinephile could happily spend half a lifetime poring over the collection — and then spend the other half a couple of miles away at the Academy's film archive, the Pickford Center for Motion Picture Study.

Here are stored thousands of movie prints, along with some 4,900 reels of home movies from the collections of Steve McQueen, John Huston, Douglas Fairbanks, Alfred Hitchcock and Marlene Dietrich, as well as rare objets, including the holy grail of film memorabilia: one of five pairs of ruby slippers worn by Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz.

(One pair is in the Judy Garland Museum in Grand Rapids, Minnesota; another — mismatched — pair in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington; the others are lost. The pair in the Academy collection is in the best condition, having been used only for close-ups.)

In the Academy's 92-year history, it has only ever entered into one commercial partnership: with the watch company Rolex. The company is a major sponsor of the annual Academy Awards and a founding supporter of the new Academy Museum, endowing a Rolex gallery, which, among other exhibits, will celebrate its long association with Hollywood. Rolex watches have made more appearances in Hollywood movies than the wares of any other brand. At the Academy Awards in 2017, the company ran a short film showing them on the wrists of Peter Sellers, Paul Newman, Faye Dunaway, Marlon Brando, Charles Bronson and sundry others — an unmatched example of product placement at the film-makers' behest, and without a dime changing hands.

Rolex also sponsors a major mentoring programme, which has seen four Oscar-winning directors — Martin Scorsese, Kathryn Bigelow, James Cameron and the Mexican Alejandro G Iñárritu — take young, aspiring film-makers under their wing, enabling up-and-coming talents to shadow them through every aspect of the production process.

Iñárritu, who won three Academy Awards in 2014 — Best Picture, Best Director and Best Original Screenplay —for Birdman, and the following year won a second Academy Award for Best Director for The Revenant, mentored the young Israeli director Tom Shoval during the making of The Revenant.

I met Iñárritu in a Beverly Hills hotel on the day the Los Angeles fires were raging. For a moment, it seemed the meeting would be cancelled — he and his family had been ordered to evacuate their home — and yet he arrived looking remarkably unruffled, clutching the one thing he'd brought from the house: his mobile phone.

Iñárritu said that when he was first approached to take part on the mentor scheme, he had baulked.

"I have always considered myself, and still do, a very bad teacher — because I was a very bad student. I'm a person who learnt about film-making by doing it. I read a lot, I saw a lot — I'm an autodidactic person who learnt from making mistakes," he says. "Every film I have done, I find out as I am doing it. So I was very hesitant about it — but then they gave me a beautiful watch, and I said, 'OK'." He laughs.

Shoval spent a month with Iñárritu on location in Canada making The Revenant, then observed the editing process in Los Angeles.

"Really, I didn't teach him anything. The only thing I thought was that if I could open myself up to somebody in order for them to see my process, be a witness of my miseries — which normally is very private and intimate — then maybe he can apply that to his own work. And we had a very miserable time on that film: it was cold, and there were physical and technical challenges. But I hate it when people say, 'We suffered...' We struggled, of course. But that's what it's supposed to be.

"And now he is finishing his second film. I think it was very helpful to him and he is very thankful to me for learning how not to do things!"

Iñárritu, who is 56, grew up in Mexico when the country was under military dictatorship and the Mexican film industry under government control. To an aspiring filmmaker, Hollywood represented a dream of freedom and creativity, and in 2001, following the success of his first feature film, Amores Perros, he left Mexico City — partly because of the violence and the risk to his family of kidnapping — and settled in LA.

It's a wonderful city in which to base yourself as a film-maker, he admits, but one that, until now at least, has proved remarkably neglectful of its own history — always looking to the future and forgetting the past.

"I think, in one way, LA was a living museum that has been destroyed. If they had had the sense of what has been happening here for the last 120 years, you would have a Charlie Chaplin museum; his studios would have been preserved. But there is nothing left.

"These guys [who built Hollywood] at the beginning of the last century were completely mad. The sets, the studios, the places where these old films were made — there is nothing. You go to Paris and here is where Balzac lived, the city he wrote about. Hollywood itself could be a museum, but this is not so. So I'm glad the Academy has a wonderful library and now this amazing new museum. It's fantastic."

Sign up for the Telegraph Luxury newsletter for your weekly dose of exquisite taste and expert opinion.