A modern day poll tax: How Republicans are trying to stop 1.4 million people from voting in Florida

When Raquel Wright received her voter information card earlier this year in the mail, she was overjoyed. The 45-year-old African American mother immediately laminated the small piece of card for preservation, and placed it in her wallet. It fitted snuggly between her Visa and the loyalty punch card for her favourite coffee shop in town.

Strictly speaking, a voter information card doesn’t do much. It’s just a card with blue and white lettering, a name, address, and party affiliation. You don’t actually need to present it to vote. But, for Wright, the moment was a relief after years of disenfranchisement believing she would never be able to vote because she had done hard time in prison – a heartbreaking circumstance for a woman whose family treats voting as a deeply important ritual and group activity.

Things had changed for Wright just months earlier, though, when an overwhelming majority of voters in Florida cast their ballots supporting an amendment aimed at putting an end to the Draconian state law barring former criminals – a group that includes some 1.4 million people – from ever voting again.

“Seeing that card come in the mail was just, like, everything was a breath of fresh air,” she tells The Independent. “I tell my daughter to be grateful and humble and appreciate everything in her life, because it is an act of freedom. And I have the freedom now to go to the polls. I have the credentials. I have the pass. I’m just so excited. I can’t wait.”

But, just as Wright was getting that voter information card in the mail, Republicans in Tallahassee were working hard to implement restrictions to the landmark amendment approved by voters last November that would have marked the largest expansion of voting rights the US has seen in decades. And if they get their way, she’ll have to pay more than $50,000 (£39,000) to the state before she can ever vote again.

The fight for Amendment 4

On 6 November 2018, the nation was watching Florida. Two years into Donald Trump’s presidency, the press had been reporting for months that all signs were pointing towards a massive blue wave. With a competitive governor’s race on the ballot alongside an equally competitive senate race, the perennial swing state that had helped usher Mr Trump into office in 2016 was seen as a key indicator of just how much trouble the president was in.

Months before that, though, as national coverage understood the midterms in Florida as a Washington and Tallahassee story, former criminals around the state were mobilising to pass Amendment 4. Seeing an opportunity to once again find a political voice, activists like Wright and others in similar situations spent their spare time collecting signatures, gaining support to restore voting rights to 1.4 million former convicts across the state.

As it would turn out, those efforts were wildly successful, even if the blue wave that swept through the national political scene wasn’t quite realised that year in Florida. On the night of the election, Wright remembers crying as she sat alone in the dark at her sister’s home, with the voting results scrolling along the bottom of her local news channel. She had stopped on her way home because she couldn’t wait to see the outcome.

The ticker told her the voters of Florida had approved Amendment 4 with a 64 per cent approval rating. In total, the measure received more than 1 million more votes than any other candidate on that year’s ballot, including the eventual winner of the governor’s race, Republican Ron DeSantis. And, considering the sheer number of people impacted, Amendment 4 represented the largest expansion of US voter rights since the passage of the 26th Amendment to the US Constitution in 1971, when the voting age was lowered across the country from 21 to 18.

“It is a monumental, generational event in the advancement of voting rights. I think it was huge,” says Sean Morales-Doyle, a senior counsel in the Democracy Programme at New York University’s Brennan Centre for Justice. “It’s hard to overstate,” he continued.

Growing storm across the country

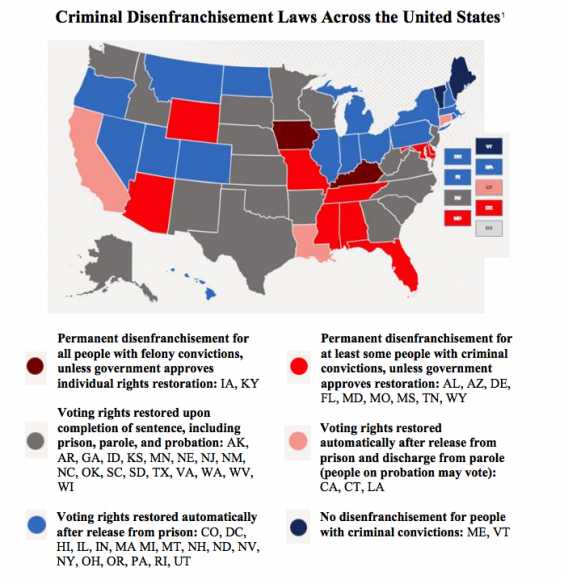

At the time of the 2018 midterms, Florida was one of three states in the United States with permanent disenfranchisement for former criminals – a Jim Crow-era policy on the state’s constitution since 1868.

While the effort was ultimately the most significant expansion of felony voter rights in American history, it was far from the first time states had taken efforts to make it easier for former criminals to become voters again. Earlier that year, New York governor Andrew Cuomo, for instance, had announced he would reinstate voting rights to returning citizens through executive order. In Louisiana that same year, around 36,000 former felons were also re-enfranchised.

The measure was also passed after the relatively successful first two terms of America’s first black president, a time that brought renewed focus on America’s criminal justice system and its disproportionate impact on African and and other racial minority groups. In Florida alone, 48 per cent of all inmates are black, for instance, even though they make up just 15.5 per cent of the population. Wright herself finds herself as a portion of this statistic, as do other former felons in Florida interviewed for this story.

While not the first in the nation, the vote in Florida focused attention on the issue in a way none of those earlier efforts had. With a bipartisan consensus in Florida – a state that voted both for Donald Trump and for Barack Obama – the humanity of allowing citizens to vote after serving their punishment was more obvious than ever.

Earlier this year, following the success of Amendment 4, Republican governor of Iowa Kim Reynolds also championed an effort to reform her state’s approach to former felons, in a failed attempt in one of just two states in the US with permanent disenfranchisement on the books. In Kentucky, incoming Democratic governor Andy Beshear promised on the campaign trail in 2019 to re-enfranchise former felons in his state, too.

America had become aware of the harsh way that African American and minority communities are targeted by police across the country, not to mention how poor people are targeted. Florida voters chose a course correction, and other states saw a model to follow. And, taken together, voting rights supporters say the efforts in Florida, Iowa, and Kentucky prove beyond reasonable suspicion that the issue is one that bridges the partisan divide across the country.

In Florida, Republicans respond to a threat on their power

Soon after the measure was approved in Florida, however, Republicans in the state had already begun thinking up ways to subvert the new law. With healthy majorities in the state Senate and House, and continued control of the governor’s mansion, power was theirs to lose.

Within the first few months of 2019, when Amendment 4 legally took effect, the state legislature and Senate – both of which are controlled by Republicans – had introduced a bill now commonly referred to as SB7066. That bill, which has now been signed by DeSantis and stayed by a court when confronted by a lawsuit that includes Wright and around a dozen others, would require former felons to pay off outstanding court fees and fines before being allowed to vote.

As Wright and hundreds of thousands of others realised they were no longer permanently relegated to a second tier of citizenship, Republicans were working to undermine a measure that was more popular at the ballot box than any elected official in the state.

“It became pretty clear that as soon as Amendment 4 passed there would be efforts by our colleagues on the other side of the aisle to delay this as much as they could,” says Anna Eskamani, a Democrat in the Florida House of Representatives.

Ms Eskamani is the daughter of Iranian immigrants, and was elected to her Orlando area seat in 2018. She says the swift efforts by Republicans this year reflect a fear in the party that major demographic changes, and the president’s divisive policies, are threatening their continued power. Amendment 4 could bring in a wave of new voters, many of them minorities, who often favour Democratic politicians over Republican ones.

“It’s this reflection of trying to control power and maintain the status quo. I think my Republican colleagues know all too well that demographics are changing dramatically, that Trump is resulting in people like me running for office, and winning,” Ms Eskamani says.

A request for comment sent to the Florida governor’s office was not returned. In late October, a court issued a preliminary injunction in favour of the civil rights groups suing SB7066. A federal hearing on the matter is set for April.

Modern day poll tax

On the surface, the fee requirement is a good governance effort, with the fiscal health of the courts being held in the balance. As a result of a 1998 constitutional amendment in the state, the courts must be funded by those very fines and fees. It’s a system that brought in $1.1bn to the state in 2018 alone.

For former felons, though, the system can often be confusing, and tying the right to vote to fines means that some like Wright, with over $50,000 in outstanding fees, may never vote again if that balance must be paid.

Betty Riddle, 62, who received her first criminal conviction at the age of 17 in 1975, and spent some 22 years struggling with drug abuse, says that even figuring out the total may be unattainable. Riddle, who has four children, 24 grandchildren, and 8 great grandchildren, has cleaned up and found solace in God. But, she has no idea how much she owes the state of Florida.

“My record goes all the way back to ‘75. So, when I went to the clerk to get all my outstanding court costs and fines, they only went back to 1990,” she says. “I tried. But really I don’t know how much I owe.”

But large sums and lost records aside, voting rights advocates say that there’s a more sinister history at work with SB7066 – one that dates back to the very first efforts by African Americans and poor whites to participate in democracy in America.

According to Carol Anderson, a historian with Emory University and author of several books on the history of voter suppression in the United States, the fight in Florida has roots all the way back to 1890 Mississippi, when some of the first measures to suppress the black vote were conceived in post-Emancipation America.

At that time, predominantly white politicians came forward to the public with what seemed like a reasonable argument: democracy costs money. Ballots don’t print themselves, nor do they count themselves. So, it only makes sense that states would require investment from voters in the form of a small fee — one that ultimately served to deny African American voters, suffering from the myriad resounding impacts of slavery, the right to vote.

The United States made poll taxes illegal in 1963 with the 26th Amendment, but Anderson says it’s hard not to see a return of the tactic.

“If you’ve been incarcerated for years, what is your likelihood of having the deep pockets to be able to pay all of those fines and fees – and those fines and fees are, frankly, very arbitrary,” she says. “So, it is now making the ability to vote dependent upon, ‘have you paid the fee? How deep are your pockets’.”

Anderson noted that, just like the poll taxes outlawed more than half a century ago, the biggest group impacted by Florida’s law are African Americans. An analysis by the Brennan Centre also finds that SB7066 would disproportionately impact African Americans.

“If you can stop that cohort, that group from voting, you can shape an electorate in a way that allows, well that is really in violation of the Constitution,” she says. “It is a poll tax, because your ability to pay means whether you can gain access to your voting rights or not. That’s why it is a poll tax.”

An ancestral tradition

Wright is no stranger to that history of disenfranchisement. As a black woman in America, she stresses that the struggle and fight to vote “goes back years, and years through my ancestry”.

Before her incarceration – a three-year sentence she received for helping facilitate the sale of 70 oxycodone pills to an undercover police officer – Wright was a teacher for 15 years, teaching students in elementary school and also adult education. Throughout that time, she and her family dutifully voted every chance they could. They would pile into cars and drive together to the county administration building where they cast their ballots.

Following her conviction, Wright still managed to help some 80 fellow inmates to earn their GED, the US high school certificate. Upon release, she was no longer able to teach, a lost passion. Since she has a college degree and the $47,000 in student loans it cost her, she was told she is overqualified for jobs at Walmart, at McDonalds, and 7-Eleven.

And, she was forced for the first time to sit in the car as her family went to vote, in 2016. She recalls vividly sitting in the back seat of her mother’s SUV as they went in to vote. Her sister returned with her dachshund under her arm, and an “I voted” sticker on its snout.

Wright says one of the hardest parts of the experience was explaining to her 11-year-old daughter why she couldn’t vote, too, and why she had left her in school on that historic day.

Now 14, her daughter is well aware of the current state of American politics. She asks about it constantly. Hoping to prepare her daughter to take seriously the immense responsibility of voting, she does her best to answer. Wright thinks 2020 is the most important election in a generation.

“I never want to sit in the car again,” she says. “That, I promise, will not happen.”