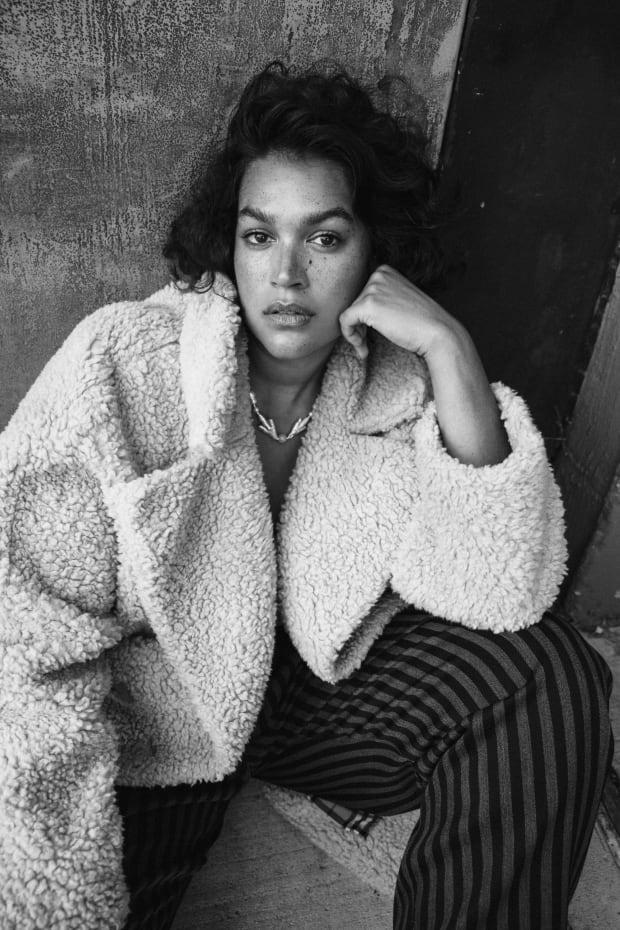

Model Jennifer Atilemile Asks: What Happened to Size Diversity in Fashion?

In this op-ed, Atilemile details her own struggles with body acceptance, from the Y2K era, to the rise of body positivity, to the recent return of "thin is in" messaging. (Trigger warnings: eating disorders, body dysmorphia.)

Jennifer Atilemile is an IMG-repped model and writer from Australia, now based in the U.S. Last week, she was named a Sports Illustrated rookie.

I'm often asked how I ended up in this career. I didn't think I'd become a model, but something about it piqued my interest during my early teenage years; it appeared to be a life and lifestyle that was so glamorous, so different to my own in the Australian suburbs.

It was the early 2000s, I had dial-up internet, and a library card so I could borrow fashion magazines. I remember going to the library after school and looking through Vogue to see the hottest looks on the runway. Fashion was always something I pined after; my parents could never afford the latest clothes sported by my peers, and it was always out of reach. It was the most exclusive and exclusionary. When I was growing up, only certain people could access it — specifically, people with money and skinny people.

Looking back at my body over the years, especially when I was going through puberty, I was never "large," although the media at the time convinced me that I was. Growing up where I did, there were two beauty standards of what a woman should look like: In fashion, we were coming out of the "heroin chic" image of the 1990s. During the Y2K and the 2000s era, clothing dictated body shape: Bones were an accessory, poking out of your low-rise jeans. Commercially, however, the other body type that was being sold to women was the "Aussie beach babe," who had tanned (but white) skin, blue eyes and blonde hair.

Photo: Courtesy of Lily Cummings/IMG

With these pop culture references, images in magazines, the rise of gossip blogs like Perez Hilton, and the proliferation of pro-eating disorder content on early blogging sites like Tumblr; my generation, even more so than the others, was essentially set up to dislike our bodies. Messages like "lose weight for summer," "crash diet this" and "how to stay skinny" were bombarding our impressionable young minds. All that millennials heard for their adolescence was that thin was in.

I had an adult body far earlier than parenting books prepared my mom and dad for; my thighs touched, my bum jiggled, and I had boobs that needed a serious sports bra — the kind that looked like something a grandma would wear. The way I was made to feel shameful for a body that didn't look like the ideal pushed me into harmful and destructive patterns of behavior. I felt that people like me weren't supposed to wear what was cool: It wasn't being made for me, nor was there diverse representation on television, runways or in the magazines I used to flick through after school.

At 15, I had a best friend who loved fashion as much as I did. We went clubbing underage and attended parties we shouldn't have been at. I was getting a glimpse into a life that I could have never imagined. I thought I was finally cool and had begun to shed the nerdy image of the girl whose life revolved around choir rehearsals and debate meets.

I didn't realize then, but that "cool-girl lifestyle" wasn't healthy. I was engaging in harmful behaviors, including disordered eating and substance abuse. *BUT* I was skinny. I had everything I thought I wanted. I spent my casual job money on the latest clothes from little boutique stores and could share outfits with my best friend, just like in the movies.

The 2000s brought with them the beginning of reality TV, including the global phenomenon that was "Next Top Model." I was noticed more at my thinnest, and many people suggested I try modeling. So, my best friend and I lined up for hours in the bitter Melbourne cold to try out for the competition show.

Just as I was ready to throw in the towel, a British woman approached me and gave me her card. She had previously worked for the iconic Storm Models and was now scouting for an agency in Melbourne. I was thrilled. This was my shot. I took part in a modeling course for eight weeks, out-of-school hours, and was placed with two agencies: one in Melbourne and one based out of Milan.

But we never signed the contract — I say we because I was under the age of 18 and my mum had to agree to it all.

We were in the meeting, and the agents basically said, "We love you, but we need you to eat more salad," and proceeded to tell me all the ways to keep losing weight. My mum, who was already worried for my health, said no, and shut the door on my dreams of becoming a model. Or so I thought.

View the original article to see embedded media.

Fast forward to 2011, when I was in my second year of university, Instagram was barely a year old and I had begun the long road to recovery from my disordered eating and body dysmorphia.

2011 was also the year that Candice Huffine, Robyn Lawley and Tara Lynn were photographed by Steven Meisel for the cover of Italian Vogue. I had discovered the world of "plus-size" modeling. My little fingers have never hit the "follow" button so hard on these models that had my body type. Suddenly, I felt like the conversation around what was deemed an "acceptable" size in fashion was changing. Body positivity had entered the chat.

Around 2015, I went to the French Island of Réunion for a cousin's wedding. I've written about this experience before, and told people how I felt when I met my family for the first time as an adult. [Editor's note: Atilemile's father is from Réunion and of African descent, while her mother is Australian and of Irish and Danish descent.] After growing up in what I perceived to be a White Australia, due to the lack of diverse representation in all the media I consumed, and surrounded by blatant racism towards my family members, meeting my family was like finding a puzzle piece that I didn't realize I was missing.

I finally saw women with boobs, thick thighs and bums that were round and jiggled while they walked. They were strong, confident and happy Black women. It was then that I began to feel more at home in my body, realizing that I couldn't fight my DNA. My body wasn't supposed to be a "skinny rake," like how my mum described hers growing up.

View the original article to see embedded media.

I started modeling at an Australian size 12 shortly after that trip. I felt like, for the first time since I could remember, I was confident in my body, that I could be as confident as those women I followed on Instagram, and felt extremely frustrated that other women could still be viewing their bodies negatively. The Instagram hashtag #bodypositivity was incredibly liberating, and helped create a fantastic community of women worldwide. Despite a lot of pushback, the discourse around celebrating and accepting all bodies was really gaining momentum.

I followed this quest for diversity and greater size representation all the way to the United States. Naturally, for someone my size, that was the ideal place to end up: There was a greater acceptance for larger-sized models, and the diversity conversation was happening, especially in 2019. That year for me was so exciting. I'd settled in New York, I walked three shows in my first New York Fashion Week season, and I'd begun to work with brands I'd only ever heard referenced on American television shows.

But, in 2020, everything changed.

We were forced inside because of a deadly pandemic, and the fashion world ground to a halt. People were dying, and the uncertainty of what was to come was felt globally. We were stressed, and barely coping with the lack of social interaction; we lived and survived through "unprecedented times."

As things began to reopen, the attitude shifted. So many of us had gained weight from being inside for over a year — which, by the way, is completely natural. Our bodies were doing the best they could, protecting us, nourishing us and supporting us through some of the hardest years of our lives. Unfortunately, this collective weight gained a name, "The Covid 15," and the desire to return to normal saw the reemergence of diet culture, with messages of "love your body" and "I am perfect as I am," repackaged as, "how to heal your gut" and "hot-girl walks" on social media.

Around the same time, fashion began rallying around the resurgence of Y2K trends including low-rise pants and midriff-baring tops. My friends and I were worried, as our memories of needing to have a certain "body" to fit the clothes resurfaced. We were all assured that body positivity was here to stay, but many of us had these gut feelings that things were changing.

I even said to a friend after September's fashion season, "Do I need to lose weight?" We were fearful not only of losing our jobs, but also of having to relive our teenage years.

View the original article to see embedded media.

The media did not assuage those fears. At the end of 2022, The New York Post published the clickbait-y article, "Bye-bye booty: Heroin Chic is Back," igniting group texts amongst my peers, and another few sessions with my therapist unpacking the reasons for my never-ending battle with body dysmorphia.

The thing is, even though none of us wanted to fall for the clickbait and feed into the hysteria about skinny ideals returning, we knew it was becoming a reality. After September's fashion season, Dazed published a story referring to the new type of fashion "it" girl, one who didn't eat, smoked cigarettes and had a cocaine addiction. Models gave interviews backstage at Dion Lee in Sept. 2022, and again in 2023, saying they didn't eat all day because of, simply, "fashion."

Meanwhile, TikTok fashion content is now reminiscent of pro-eating disorder Tumblr, and with the growing popularity of extreme medications like Ozempic, it is very clear that the outmoded "thin is in" philosophy seems to be creeping its way back in. There is a return to skinny on the runway, and we are once again shifting back to the exclusivity and exclusionary fashion industry of yesteryear.

I feel like my generation — those of us who have already lived through one heroin-chic trend cycle — has the tools to manage another, but I worry for the next generation and the ones that come after. I fear for the very impressionable young minds I wanted to help create an inclusive space for. We didn't have the internet and social media in the same way they do. These kids are growing up with filters and apps that distort their bodies, their perceptions of themselves, their perceptions of others, and the way they present themselves online. They're growing up in a society that is actively trying to cancel the very things that make our world beautiful: being unique and embracing true diversity.

My body has fluctuated over the years; I've been a size six, a size 16 and a size 12. What hasn't changed is my love for fashion. I'm sure there are already people studying the cultural shifts taking place post-pandemic/pre-recession, but it's really disheartening to see so many years of activism and hard work — from agents, models, casting directors and designers alike — seemingly disappear in one fashion season.

We all know that quote from "The Devil Wears Prada" about cerulean. Let's hope the lack of body diversity this season doesn't trickle down to the department stores and clearance bins in the same way.

Never miss the latest fashion industry news. Sign up for the Fashionista daily newsletter.