A Mayor Named Keisha

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

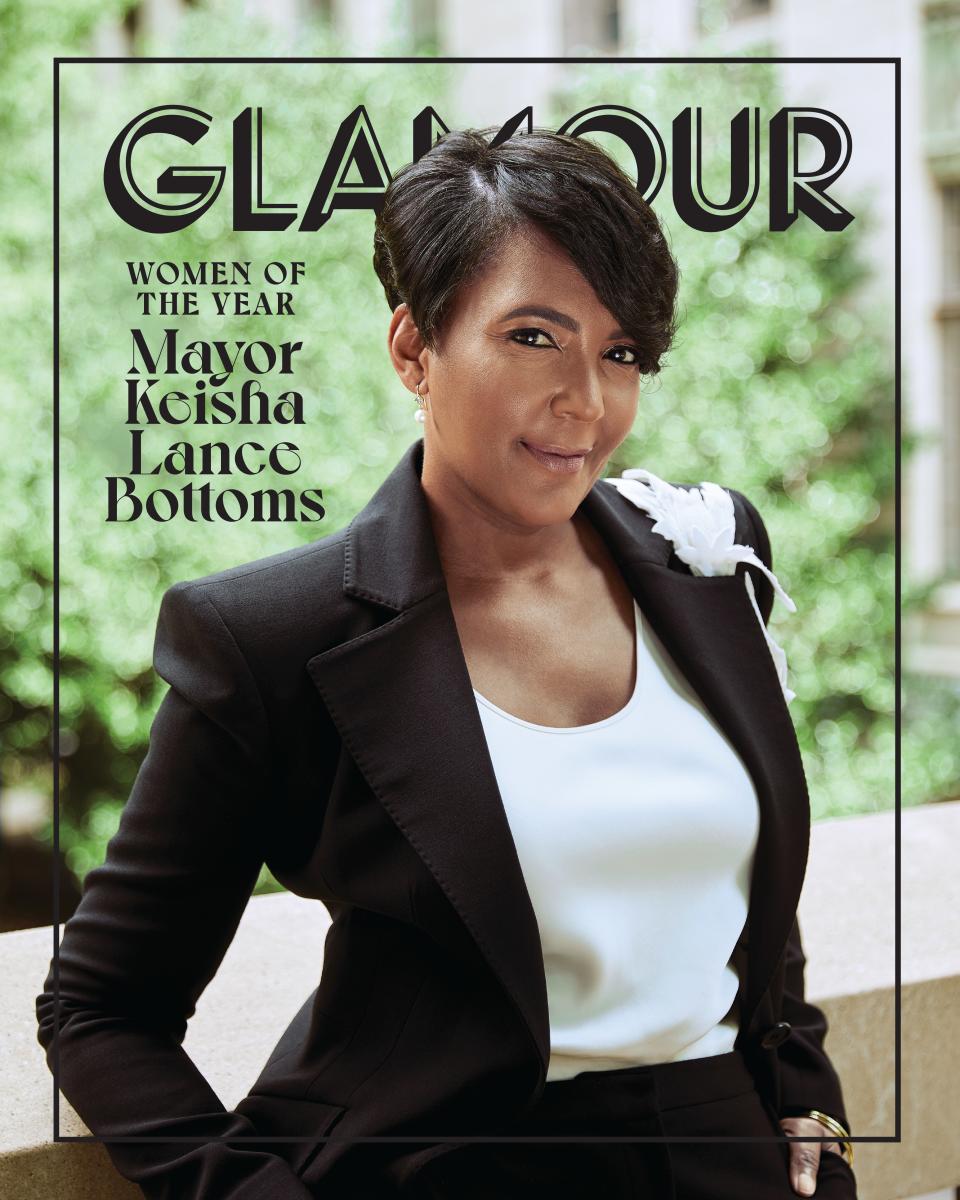

On the night of her inauguration as the mayor of her hometown in January 2018, Keisha Lance Bottoms looked out at the crowd and declared that “only in Atlanta could a young girl named Keisha…go on to become the 60th mayor of the great city of Atlanta.” An outsider might not know quite what to make of this pronouncement, but everyone in the packed hall on the campus of Morehouse College, a storied historically Black college, knew exactly what she meant.

It starts with the name, Keisha. It’s not a name handed down from previous generations, nor is it aspiration borrowed from television heroines. Keisha is a name that became popular in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Black parents adopted names entirely their own. It has since become a shorthand way of referring to Black women of Generation X—be she the woman who works in the post office or your mother’s wise-cracking best friend, the deaconess at the Baptist church or now the mayor of a major American city. Such was the significance that local rap artist TopNotch composed a song in her honor, “Atlanta’s Got a Mayor Named Keisha.”

Thus began the optimistic days after her swearing-in. It had been a hard election, decided in a run-off by fewer than 900 votes. And her work was cut out for her. Accusations of corruption and graft had dogged the office she’d just assumed. Still, she set herself to the agenda she’d campaigned on: affordable housing, greater transparency in City Hall, and increasing pay and benefits for police and fire department workers—all issues that enjoyed popular support. But she also addressed controversial concerns like severing the city’s relationship with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and restricting cash bail (the practice of keeping defendants behind bars if they can’t afford bail, even though they have yet to be convicted of a crime). “I had cousins that were locked up for three months for a broken taillight,” Bottoms explains. “I know the ones who get locked up because they can’t pay the probation fees.”

She was making her mark, implementing her policy goals. She began this year fighting to retain city control of Hartsfield-Jackson, the busiest airport in the world. In January this seemed to be the most significant obstacle of her first term. And then the pandemic hit.

“Welcome to 2020,” the mayor quips when asked about her morning. She recounts preparing citrus waffles for her children (she has four, ages 9 to 18) and situating them for distance learning. “I’m basically a short-order cook,” she says with a laugh. “It’s never a dull moment. No sooner do you fix breakfast and then at 11:05, it’s lunchtime and…I am frying fish, and my husband is doing some meetings, and the dogs are barking.” All the while, Bottoms is preparing for interviews and, of course, handling the business of being mayor.

She makes it sound easy, but when pressed for details, she loses her breezy affect. Her warm smile cannot quite conceal the stress of the compounding challenges that have demanded that Atlanta’s mayor step onto the national stage.

In this unprecedented year, crises have not politely waited in a single-file line. As America has faced simultaneous pandemics of COVID-19 and systemic racism, no one could have predicted that Atlanta would become the center of life-or-death clashes over mask wearing and police violence.

Black Lives Matter protests, Atlanta, USA - 04 Jun 2020

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, an unarmed Black man in Minneapolis, died of asphyxiation, his neck under a policeman’s knee, before a crowd of horrified onlookers, one of whom filmed the tragedy. As the video went viral, the nation’s streets filled with protestors. On May 29, the fourth night of protests, the Atlanta resistance turned violent. The Omni hotel—once the jewel of the city and now the headquarters of CNN—was attacked. Its restaurant was looted. Organized protests had descended into chaos. When Bottoms took the microphone to address her hometown, the nation turned its eyes and ears to the first-term mayor.

She began her remarks with a reminder to the room: She is the mother of four Black children, including a son who is 18. “So you are not going to out-concern me,” she said in a now often quoted remark. She invoked Atlanta’s legacy as the cradle of the civil rights movement. And she urged the protestors to “go home” out of respect for not just current leadership, but the “Black mayors and Black police chiefs” who’d come before her.

The Atlanta way is a term coined in the early 20th century to emphasize the symbiotic relationship between commerce, politics, and the Black community in the city. When Bottoms took the microphone, followed by the rapper and activist Killer Mike, both spoke with the kind of love and supplication that’s tinged with pride. But five months on, the mayor reflects on the downside of this way of thinking: “The other part to that, I think it oftentimes breeds complacency. And that’s what you saw over the past several months in 2020. This complacency that, ‘No, you don’t have all those problems in Atlanta, because this is Atlanta! Fifty percent of small businesses are minority owned. We have good jobs here.’ But the reality is that we have the largest income inequality gap in the country. There are still so many communities on the outside looking in.”

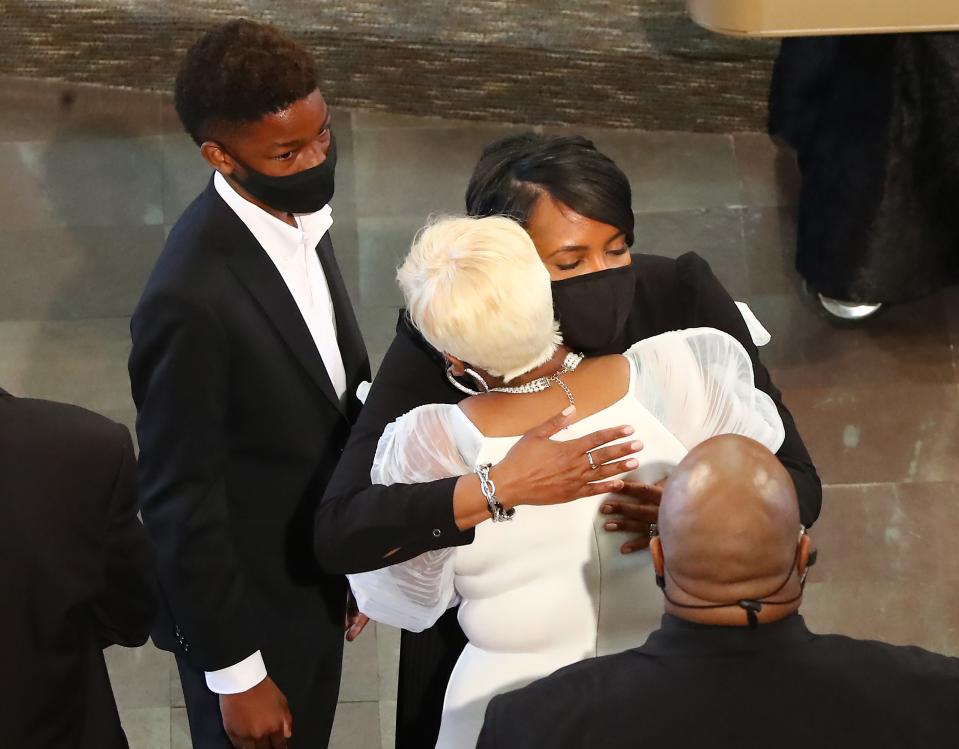

The truth hit home and hit hard just over a week later when police shot and killed Rayshard Brooks, an unarmed 27-year-old Black man and father of four, in the parking lot of an Atlanta Wendy’s restaurant. Bottoms took immediate and decisive action. She called for the termination of the officers and she accepted the resignation of the police chief. The district attorney filed the most serious charges at his disposal. In the several tense nights that followed, the Wendy’s restaurant was set aflame, but Atlanta was left standing.

Funeral Held For Rayshard Brooks In Atlanta

Bottoms barely had a moment to catch her breath before she received more alarming news. She and her husband and one of her sons tested positive for COVID-19. Bottoms herself was asymptomatic; her husband experienced more of the virus’s effects. Even now, months later, he suffers from daily headaches and fatigue. When she speaks of his difficulty performing basic tasks like operating the barbecue grill on Labor Day, her voice shakes with sadness and anger. “It wasn’t even that hot outside, but he came back in the house and it looked like someone had dumped a bucket of water over his head. He had to go and lie down. This is someone who went into COVID completely healthy.” But she follows up with deep-felt gratitude: “We count ourselves fortunate. Nobody died in our family.”

Guided by the advice of scientists as well as her first-hand experience of how contagious and dangerous the virus is, Bottoms issued a citywide mask mandate on July 8. Georgia governor Brian Kemp, a staunch Republican and Trump ally, responded to her efforts to save lives by filing a lawsuit against her.

But Bottoms is no shrinking violet. She fired back on television and on social media. In a tweet, she wrote: “3,104 Georgians have died, and I and my family are amongst the 106k who have tested positive for COVID-19. Meanwhile, I have been sued by @GovKemp for a mask mandate.” When the governor still didn’t back down, she responded in a Today show interview: “We will see him in court.” Ultimately the pair went into mediation and the governor withdrew the lawsuit—an understated conclusion, perhaps, but a victory that was anything but. “I’d rather go down fighting,” she says, “than stand as a loser.”

To understand the incredible rise of Keisha Lance Bottoms, you must first understand Atlanta. And to understand Atlanta, you must understand the South. In recent years much has been made of the wave of new politics below the Mason-Dixon Line. Major cities in Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, Arkansas, and yes, even Mississippi are helmed by African Americans. Why is it that a region so often cited as a shorthand for racial oppression is now the hub of Black political power? According to Chokwe Antar Lumumba, mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, “The greatest organizer of all time is oppression.”

The case of Atlanta—and Bottoms’s role leading it—is a bit more complicated. Like scores of southern municipalities, Atlanta meets the sociological standard of hypersegregation. While the term conjures images of red-lining and extreme poverty, Atlanta is at the top of the column of a less academic category: chocolate cities. These are places—Washington, D.C., and Detroit among them—where a critical mass of Black professionals, intellectuals, and entrepreneurs defines a place’s culture. Atlanta is home to four historically Black colleges, was the birthplace of civil rights icon Martin Luther King, Jr., and contains within its limits the historic Cascade Heights neighborhood—a showpiece of African American upward mobility.

Congressman John Lewis Freedom Parkway unveiling in Atlanta, Georgia, USA - 22 Aug 2018

Coming of age in Atlanta, Bottoms was three when, in 1973, Maynard Jackson was elected mayor of “the city too busy to hate,” ushering in a still unbroken streak of Black mayors. Educated at Frederick Douglass High School, she never had any sense that City Hall or other venues of power were unavailable to her just because of her race. Perhaps she was even a little overconfident. “Growing up in Atlanta, you weren’t led to believe that it wasn’t possible, because you saw it. You turned on the television; there are Black people on TV. You went into the grocery store; there were Black people in the grocery store. Your mayor was Black. All of this greatness was a part of our day-to-day existence.”

Recalling her 2008 run for a seat on the bench of Fulton County Superior Court, she says, “I didn’t have sense enough not to challenge the incumbent.” She shares this without rancor, a smile on her lips at the memory of her aspirations. Her opponent, she explains, “was doing a terrible job.” She lost but ran the next year for City Council and won. The rest, as they say, is history.

A little more than a decade later, her ambition has been seasoned with experience—and a knowledge that leadership, resistance even, is in her DNA.

Her aunt, Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, is an unsung hero of the civil rights movement. Smith Robinson, while a student at Spelman College, was one of the founding members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, best known for the Freedom Rides in Mississippi to oppose segregation. Despite beatings and sentences that forced her to spend over 100 days incarcerated, Robinson was one of the first to follow the “jail, no bail” strategy of civil disobedience. Although she died at the age of 26, in 1967, three years before Bottoms was born, her legacy was kept alive in Bottoms’s household.

“She was fierce,” the mayor says. “I would always hear the stories of how courageous she was. She was a big part of our conversations. She was always present.”

The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon - Season 7

Public service was a value Bottoms learned at home, not just because of her aunt’s example but because, as she puts it, “it was just how my grandmother raised us to be.” It wasn’t until she went to college and pledged Delta Sigma Theta that she learned there was a formal term for providing assistance to those who needed it: activism. This commitment to the collective has won over her city.

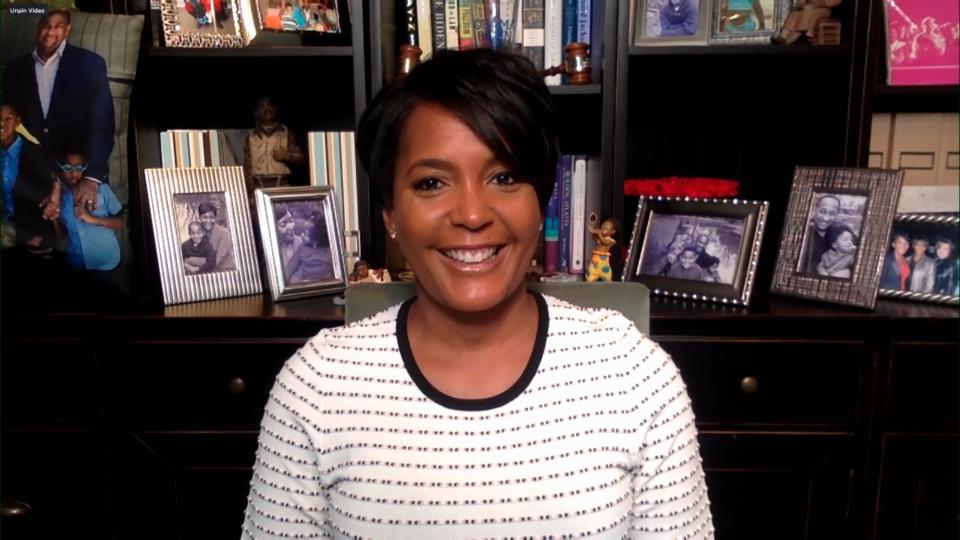

Bottoms is still grounded in those inherited values, and family is central to the mayor’s worldview. This is clear in ways that are both symbolic and demonstrated. When she provides remote commentary to news outlets, she arranges herself before an array of photos of relatives and heroes rather than framed diplomas. In a socially distant era, Zoom backgrounds have become as much of a statement as words spoken aloud, and her perspective is clear: “My people are my credentials,” she seems to say.

Among the smiling faces is always her late father, the Grammy-nominated musician Major Lance. Born in Mississippi to a family of sharecroppers and raised in Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing projects, Lance struggled to support his family while nurturing his artistic aspirations. Against all odds, he opened for The Beatles and even gave an opportunity to a young musician named Elton John to open for him.

Photo of Major Lance

“When I am at my best, I am my father’s daughter,” she has said in the past. She is less restrained on the day of her Glamour Women of the Year shoot. When asked about him, she gets emotional. “My dad always believed in the best in me,” she says. “He was the one who always made me think that everything was possible. And he would say, ‘Did you try, did you ask? All they can do is tell you no.’ And he always pushed me in such a loving, comfortable way. He believed that I could do it all. All I had to do was believe I could do it. And he taught me that it was okay to fail. But the real failure is if you didn’t try. My father wasn’t a perfect man, but he loved me in this perfect way.”

Overcome, she doesn’t elaborate, but she has spoken about her father’s struggle with addiction and incarceration before. In 1978, Lance received a 10-year sentence for possessing and selling cocaine. For Bottoms, these societal scourges are not just ideas or campaign issues; they have been her reality.

“We need leaders with a wide range of experiences,” says Chesa Boudin, district attorney of San Francisco and an admirer of the work Bottoms has done in Atlanta. “I speak often and openly about my personal connection to incarceration. I believe my experience growing up with parents who were incarcerated—my father is still in prison—helped shape my perspective and understanding of the harms mass incarceration inflicts.”

Blurring the lines between public and private has been a hallmark of Bottoms’s approach to governance. Her Twitter profile identifies her as “60th Mayor of Atlanta | Wife & Mommie.” Her children are never far from her mind. “It’s difficult for me not to see everything through the lens of my kids, and how they see our city, and how they feel our city. And right now, what I see with my kids is, I see a lot of anxiousness. I see a lot of uncertainty, and they are looking to me as their mother, and their friends are looking to me as mayor, to make it okay. And I think that’s the responsibility and burden that women often carry. That we’re supposed to be the healers, we’re supposed to make everything okay. That is what I wear. I don’t count it as a negative. I count it as a privilege.”

Similarly, when Atlanta was shut down, Bottoms posted a photo of herself having her hair styled in her mother’s kitchen. The caption of that particular image was a tribute to love between mother and daughter, but the underlying message was clear—during the height of the pandemic, not even the mayor was visiting her hairdresser. In southwest Atlanta, where there is a salon on nearly every corner, this was her way of sounding the alarm, underscoring the urgency of our national predicament with a visual lexicon accessible to all.

Bottoms is a hometown hero, but in 2020 she has also become a national figure. After she endorsed former vice president Joe Biden early in the primary season and gained attention for her bold action in the face of crisis, Biden reportedly considered her as a running mate. As the veepstakes heated up, Atlanta held its breath. When she was not selected, the reaction was disappointment mixed with relief. The city would be able to keep its native daughter at least a little bit longer—although she won her office by the narrowest margin, her second term is all but all assured.

Now when contemplating the future, the mayor named Keisha is sanguine. “I’ve been asking God to show me,” she says. “What I know is that when you don’t know, you just stay still. And there’s so much work to be done here in Atlanta.” Still, everyone knows that she is destined for much, much more.

Photographed by Ari Skin; styled by Kah Li Haslam; hair by Lisa Pope; makeup by Mariela Perez; produced by Brittany Bowman-Harris; mural artist: Shanequa Gay.

Originally Appeared on Glamour