Matthew McConaughey Has No Regrets

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

THE FIRST OF HIM we ever saw was a hand. Matthew McConaughey’s right hand resting open across his tuxedo buttons in a commercial for Al’s Formal Wear, in 1991.

Back then, they were working hands. Playing hands. They’d built tree houses and spun truck wheels and driven golf balls far down Texas fairways. They had not yet gripped trophies or pounded bongos or worn handcuffs. They were not yet movie-star hands.

Perhaps there exists a universe in which that hand is all we ever saw of McConaughey, a universe in which that was all we remembered or judged him by. But that universe was not to be ours. In our universe, it was the face that paid the bills. It was the face by which he would be judged.

The hands are 50 now (and some change). The fingers swell around two rings—one silver and copper to protect the owner from evil thoughts, the other a wedding band.

They rise now in front of the screen on a Zoom interview, when McConaughey is asked about the first time we ever saw him. “Al’s Formal Wear. And it paid 150 bucks,” he says with a grin. “My hands. They didn’t pay the rent, but they bought me a few drinks.” The grin seems to linger forever.

MCCONAUGHEY MOVED to Austin 12 years ago, and he’s been home nonstop since spring—save for “one little out to Hawaii for a week and a half to get outside and get some sun.” He’s “hunkered down” now with his wife, their three children, and his 88-year-old mother. He’s recruited his kids (7, 10, and 12) to handle all his photo shoots and commercials—so far, one for Longbranch Whiskey and some pics for People magazine. He told them they’ll get paid, but only if the photos run. Fifty bucks for inside the magazine, he told them. Seventy-five for a cover.

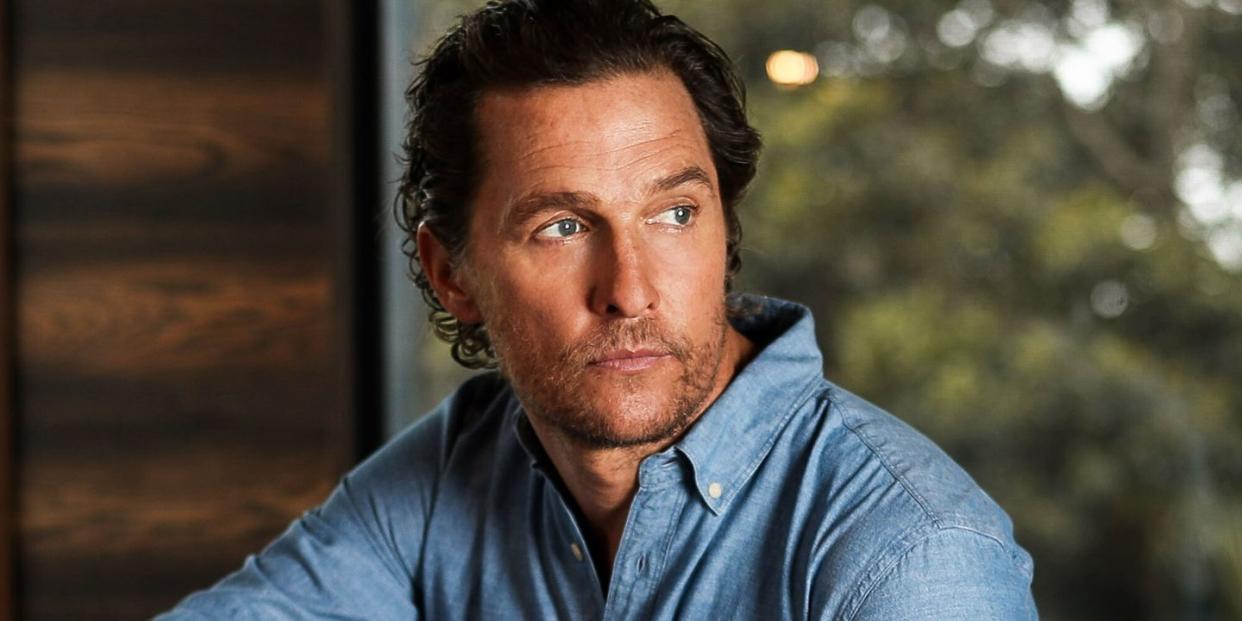

He is now full-time homebody but somehow still looks peak McConaughey. His long hair is permanent pomade. His beard is eternal scruff. His shirt an untucked button-down—unbuttoned one on top, one at the bottom. He’s sitting in what looks like a study and wearing his dark-rimmed glasses, which make him look especially professorial.

McConaughey just authored his first book, Greenlights, a memoir that earnestly shares a sort of philosophy he’s developed over the years. How various obstacles and tragedies in his life (red lights) actually turned out to be opportunities for growth and understanding and success (green lights). Once you accept that the red light is there, you can prepare to change it and move forward.

For McConaughey, the red lights have ranged from feeling lonely and isolated on a year-long high school exchange trip in Australia, to the unexpected death of his father while he was busy seizing his debut role in Dazed and Confused, to that moment, on the edge of 30 years old, when he realized he was typecast as a RomCom Guy and being passed up for the serious scripts he desired. As he puts it: “All the stories are true. They’re mine. I told them.”

But the way he tells them is important, too. His philosophy is delivered with a self-awareness that some people still might not be expecting a Matthew McConaughey book to contain. And he leans into that. In an epigraph immediately after his memoir’s intro, he quotes, unironically, his own much-parodied Lincoln advertisement. (“Sometimes you gotta go back to actually move forward.”)

When we talk, he brings up his 2014 Oscar acceptance speech after winning for his depiction of Ron Woodroof, an AIDS patient struggling through the 1980s, in Dallas Buyers Club. Anyone who saw the moment should remember that it included a repeat of his now practically trademark catchphrase (alright-alright-alright!) that McConaughey fans could add to the meme cannon. But he made everyone wait for that, while first sharing something seemingly far more important: He tries to get better each day by chasing the idea that whoever he becomes might have been an inspiration to his former self. That message, he emphasizes, is the most valuable thing. “As I said in the Oscar speech, my hero [should be] me in 10 years—ooh, who am I in 10 years?’” he says. “I’m 50 now. What if I had a conversation with my 70 year old self? That’s a great fun exercise to do.”

This might seem strange coming from a man whose life already seemed pretty enviable during the jacked and shirtless rom-com years of the early aughts. What’s so wrong with making millions for playing an affable sex symbol confident enough to also play the bongos naked? What no one realized until he went rogue for two years, turning down huge paydays and taking a risk to see if directors would begin to think about his other strengths, was that anything that superficial might also be a trap. Eventually, even sex symbols may feel stagnant. “I’ve had times where I’m complacent,” he says. “And if I’m complacent, that usually means I’m being lazy.” He whistles. “Well, right when you do that, life, hell, deals you a frickin’ joker.”

Outwardly at least, McConaughey never seemed particularly concerned with people laughing at him. In fact, each of his wayward heroes seemed to arrive onscreen with just enough of a wink for us to know that McConaughey was probably chuckling alongside us. But he’s a strong believer in the power of self-reflection. “That’s a form of prayer,” he says. “That’s a form of writing a diary. That’s a form of looking in the man in the glass, the man in the mirror.”

In practice it’s allowed him to become a 50-year-old who continues to take more risks—in his career, in how he relates to others, in how open he is to admitting he still doesn’t have it all figured out. While we might roll our eyes at his earnestness, we all have red lights in our own lives, and sometimes we’re too intimidated or insecure to work through them. The path to green starts with finding the courage to address our own insecurities. And luckily, McConaughey has an accessible koan for that. “As I say, life is a verb,” he says. “We never get to a spot where we have the answers and we all got it all figured out. We’re constantly working. And that’s, I believe, the best we can do.”

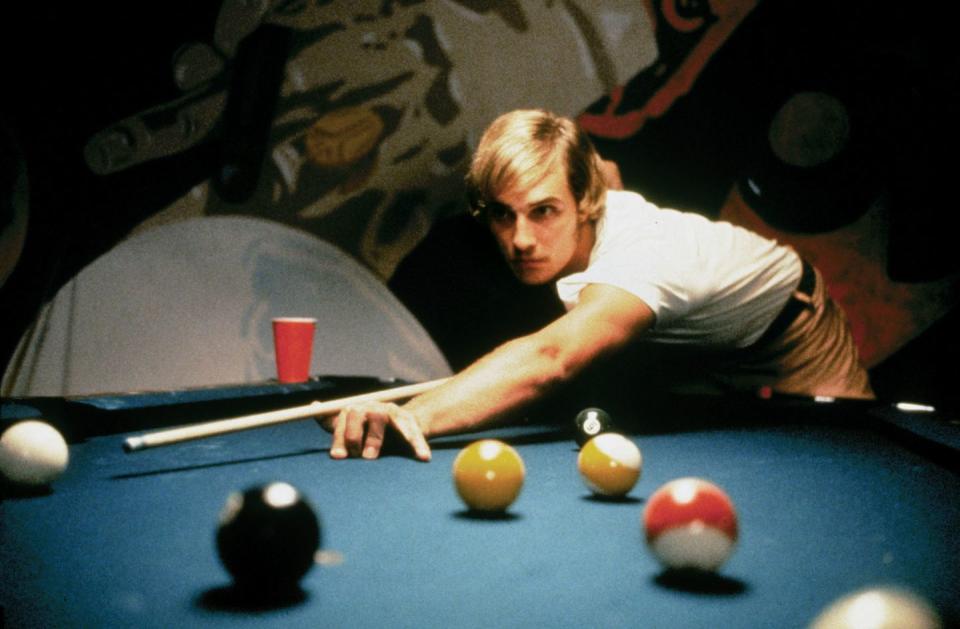

THE FOUNDING LEGEND of McConaughey, which is retold yet again in his memoir, starts inside the bar at Austin’s Hyatt Regency hotel. The 22-year-old found himself sitting next to Don Phillips, the casting director for Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused. The two got so uproariously drunk that management kicked them out. But the two kept the night going anyway. McConaughey was later cast as infamous high school partier David Wooderson.

In 1996, after McConaughey scored his first serious dramatic praise for A Time to Kill, Philips told Vanity Fair what he saw in the young man, aside from just a great human being: “Let’s face it. Matthew’s got those three things that make a star: you got to be smart, you got to have talent, and the girls have got to want to fuck you.”

By 2008, many were convinced McConaughey had settled on that last condition. He’d spent the better part of the decade playing various shades of hunky. (See: The Wedding Planner, How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, and Fool's Gold, among so many others.) It seemed like Oscars weren’t important. And offers like A Time to Kill certainly weren’t arriving.

“No one will ever give a good-looking guy, especially a leading man, credit for acting ability,” Linklater, McConaughey’s first director, said later, summarizing the actor’s general typecasting. “The advantage that a Philip Seymour Hoffman would have is that he can just disappear in the character. But people don’t want Matthew to disappear. They want to look at him.”

I ask McConaughey about this sexualization now, years later. In a time when intimacy coordinators are rethinking how Hollywood shoots sex, I ask how he remembers those moments—pre-McConaissance—when the market value of him was his grin and his unbuttoned chest.

“I grew up [shirtless] long before I ever had pictures of me on the beach with my shirt off. I grew up wearing cutoffs and no shoes and no shirt. I mean, every picture of my childhood, I barely have a shirt on. It was hot in Texas.” He pauses, thinking. “No, I never had that feeling through work like, you know... that I was being exploited.”

But although he reveals many stories about his life in his memoir, there are some events McConaughey isn’t all that interested in expanding on. In an opening chapter titled “How Did I Get Here?” McConaughey makes a list of surprising facts about himself. He says he wanted the chapter to destabilize readers. Shake the floor. Make you question whom you envision when you envision “Matthew McConaughey.”

In successive lines, McConaughey describes two abusive experiences. The first reads: “I was blackmailed into having sex for the first time when I was fifteen.” The next line reads: “I was molested by a man when I was eighteen while knocked unconscious in the back of a van.” McConaughey never mentions the experiences again.

“That’s not a story that I care to share right now. Or in this book,” he says, when I ask him why he chose not to revisit the second sentence later in the work. “It’s not a story that, as far as I can tell, has left any scar of victimhood on me. It’s not a scar that I’ve carried through my life, that is psychologically holding me back.”

At the time, he says he talked to some close friends about being molested but never brought it up with his parents. “It wasn’t permanent in my brain,” he says. “I was able to go, ‘Nope, that’s done. That’s not gonna be something that defines me.’ It was a fucked-up moment. It was a fucked-up time. I am glad I got out of it without being really, really harmed. I moved on. Turned the page on that. Didn’t really look back at it.”

His father’s death in 2002, however, changed his outlook dramatically. From there, he began a different thought process. “I better man up,” he recalls thinking. “[I better] put into action and own more of myself and own what I’m about and own what I’m for and what I’m against.”

All of this may have eventually played into him quitting rom-coms cold turkey after Ghosts of Girlfriends Past in 2009. A couple years later, after turning down payouts as large as $14.5 million while waiting for the phone to ring with more serious offers, he reemerged in the title role of The Lincoln Lawyer, a totally different legal thriller. Enter the McConaissance: Mud, True Detective, Dallas Buyers Club, The Wolf of Wall Street.

“I don’t believe I would have the courage that I’ve had to try and be the man that I am if [my dad] had still been alive,” McConaughey concludes. “Because I would have relied on him to be there, to be my crutch, to catch me when I fall. I was like, Oh, the crutch is gone.”

WITHOUT THE CRUTCH, McConaughey stumbled a bit as he learned new lessons on his quest for perpetual progress. “I'm not making straight A’s in these,” he says about the ideals outlined in his book. “Sometimes I'm making C’s.”

Case in point: In June, he appeared on Emmanuel Acho’s YouTube show Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man. McConaughey called Acho after seeing the first episode, which encourages candid discussion about race. “Ah, this is just great,” he remembers thinking at the time. “Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. This is constructive.”

McConaughey wanted to learn more about how he could be a better man, a better father, a better human. “I’m here to learn, share, listen, understand,” he said, after Acho introduced him as the first guest to appear on the show. McConaughey’s first question: “How can someone like me, how can I do better as a human? How can I do better as a man? How can I do better as a white man?”

Acho challenged McConaughey to recognize a problem—a difference in the professional treatment of Black job applicants—and asked him rhetorically how he, as an employer of others, contributes to that problem—how he reads an application, how he may hold racial bias. The 12-minute discussion has since drawn 2.3 million views. When I ask McConaughey if he’s still thinking about what he and Acho discussed, he tells me another story about his children taking virtual classes.

“Online school. My son and daughter each have a person that they’ve become friends with in their class. And talk to a lot. Even after class, they’ll talk and they’ll Zoom or FaceTime each other. All I could do is hear the voices talking.”

One day, McConaughey asked them who they were talking to. They answered “Terrance” and “Judy,” and they told their dad about how funny and smart Terrance and Judy are.

“A month of this goes by,” continues McConaughey. “I walk by the screen one day and they’re talking to those friends. And [I see] they’re both young Black children. What was beautiful and simple is that my children told me—when I said, ‘Who is that?’—they said their names. And they talked about what they liked about the person. … The color of the skin never came up. It wasn’t part of the definition from my kids’ eyes.”

It was another moment that led to more self-examination. “I thought back about times when maybe I have defined someone by the color of their skin or their sex” he continues. “When, ultimately, it ought to be how my kids told me about their friends.”

THE MCCONAISSANCE may be as much a personal evolution as a professional one. McConaughey still thinks about if he's happy with his own reflection. If he’ll be happy with the man he sees in the future. But he has one more tool he likes to use to drive all of this home emphatically. When he’s flowing, McConaughey will speak in staccato as if he’s dictating to a scribe and will often raise his voice as if to signal an underline.

“We’re writing our résumé with our life every day,” he says. “Once we die, someone else will introduce us for the rest of time. It is a good process, I believe. A prudent process. To go there and [ask], ‘Ooh, what do I hope they say? Ooh, what’s my eulogy gonna be?”

“When it comes to living for your eulogy,” he asks, “who is the one person we’re stuck with?” The answer is yourself. You are the one person who can control how you’re remembered. But as McConaughey sees it, that shouldn’t stop you from pushing yourself in new ways, even if it leads to failure.

“None of us are ever going to be our ideal self,” he says. “That’s the deal. That’s what I'm saying—‘Don’t be best, be better.’ There’s no best. There’s no perfection. There’s no landing spot we go ‘Tadaahhh, I’m enlightened, I found it, I got it figured out.’ Bullshit!”

But there are little ways you can probably make life easier on yourself. “I mean, let’s talk about a simple thing. Simple tee-up of a green light you can do for yourself: Put coffee in the coffee filter in the coffee maker at night before you go to bed! Doesn’t it feel great when you come out the next morning and you go, ‘Ooh, all I gotta do is press the button’? Boop! Doesn’t it suck when you’re going, ‘Jesus, where’s the coffee?’ ... Like, ‘Dammit, why didn’t I just do this last night?’ Because: Sometimes it’s hard to make your coffee when you haven’t had your coffee!”

The most important part seems to be celebrating the journey along the way. “Sometimes doing something for pleasure’s sake [is good],” he adds. “Yes, eat the fucking ice cream. It’s good. ‘Yeah, but tomorrow?’ No, shut up. Don’t hem and haw about tomorrow and looking in the mirror feeling like you put on a pound.”

But the next time you see your reflection, what will you say to it? What would McConaughey say? What would he ask himself?

“Here’s the question I would ask. I think everyone should just ask themselves. It’s a two-word question.” He takes a pause … “I value?” As in: What do I value? “The asking of that question is never going to go out of style,” he says.

McConaughey says his answer is his book. But he knows the answers will change as he keeps trying to grow, keeps trying to be better, not best.

“The [thing] I’m ultimately chasing? On my deathbed, I look back and I go, “Alright, good job, McConaughey.” The [thing] is, if there’s a place to go after this life, that I’m welcomed in. And whoever’s there goes, “Good job, McConaughey.”

You Might Also Like