Martin Luther King Jr., American Preacher

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article originally appeared in the December 1983 issue of Esquire. You can find every Esquire story ever published at Esquire Classic.

Although the modern civil rights movement was truly popular and spontaneous, its undisputed prophet was the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In the heyday of the movement, despite the violent confrontations that King fought hard to pacify, miraculous changes occurred in a relatively short time. The lunch counter, the public school, the city bus, the voting booth were thrown open to Americans who had been so long shut out. And it was King’s sermons that kept the march going: “Free at last, free at last, thank God Almighty, we are free at last.”

I begin with the first scene in the fall of 1956, when the South was still as it had always been. The Montgomery bus boycott had recently begun; Martin Luther King was just beginning to come to national prominence, and he had come to Nashville, Tennessee, to speak. I am not sure of the date; in the archives of my memory the scene is still black and white, and in part that is because racial scenes from the South remain clearer that way, but also because color television had not yet come to the country.

In those days I covered some aspects of the civil rights movement for the Nashville Tennessean, but when I went out to the black church where King was going to speak, if I recall correctly, I went on my day off. On the Tennessean we prided ourselves, with considerable justice, that we were a good paper, willing, unlike most southern dailies, to cover racial stories. But even a good and courageous paper like the Tennessean did not necessarily look for trouble, and sending a twenty-two-year-old reporter from the North to cover an outspoken young black minister constituted trouble. Besides, good as we were on basic questions such as integrating schools, we had nonetheless a few idiosyncrasies of our own. Just a few weeks earlier I had done a story on four young black women training at Tennessee State who were going to compete in the forthcoming Olympics and who were, in fact, to excel in the women’s events—Wilma Rudolph was among them. In my lead I had referred to “four young coeds” at Tennessee State. The story had been bounced back with orders to rewrite the lead since only whites could rightfully be called coeds. Such were those days, even on a good newspaper.

The black church probably held fifteen hundred people, and perhaps six thousand had turned out. There had been no announcement in the paper or on television, but they knew. It was a very orderly and respectful crowd, including those who knew they would not get in. I went around to a side door, sure that the press—in this case it was likely to be only me, the media battalions would come later—could be squeezed in. As I entered I saw a Nashville cop who was a nemesis of mine, a hard-core segregationist for whom being a cop was as much as anything else a means of expressing racial hatred. He nodded and spoke to me; he favored me because I was the only other white face there.

“All this for a nigger preacher,” he said.

I nodded at him.

He looked around again, saw the immensity of the crowd, and his face hardened for a moment. “I’ll bet he sure can get them going.” That seemed to please him, the idea that it would be some updated version of the old revival meeting, a jackleg preacher holding forth and all kinds of blacks a-whooping and hollering and rolling on the floor. Feeling better, he smiled slightly and waved me in.

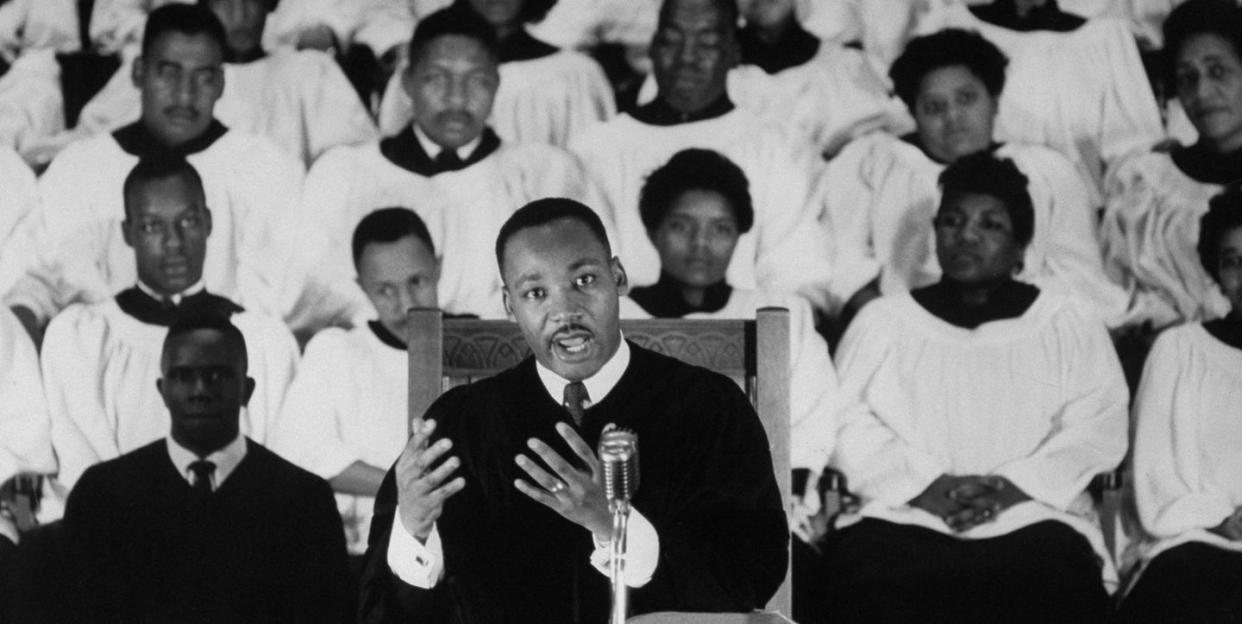

That was the first time I heard the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Now, more than twenty-five years later, it is remarkably easy to recall his impact. The words have gone, but not the power and the intelligence and the force of the performance. In particular, I remember the special communion in that church between minister and congregation as he and his audience shared with each other. He brought to them his high intelligence, his fierce will, his rare capacity to phrase new truths in old ways, and that strengthened them. And they brought to him their abiding dignity, with which they had suffered through years and years of hardship, and that in turn strengthened him.

Martin Luther King Jr., whose father was a famed preacher and whose grandfather was a famed preacher, was bringing the new social gospel to the old southern black cadence. The gospel cadence was time-honored in those churches; it was a way in which a black preacher allowed his congregation to minister to their wounds and express their emotions without confronting the white ruling class. But Martin King was challenging that, for his ideas were powerful and, if acted upon, they meant that everyone in that church was going to have to confront the white community. In the white vernacular of the time, he was stirring them up. Normally they might have been wary of some almost-unknown young minister from another state asking them to take such great risks. But Martin King was special; he was able to speak those new truths and at the same time remain of them, while someone else espousing the same ideas might have seemed desperately alien. What he was saying was simple; it was that the fault for the hardship in their lives lay not with them but with those who mistreated them. That does not seem terribly radical now, but the black-pride part of the movement was still years to come and the average southern black was still mired in terrible self-doubt and self-defeat. So King was in effect giving them back a critical part of themselves. His voice seemed to be as much theirs as his. He was destined to be a Nobel laureate, the most important black leader of his generation; but then, when I first heard him, he was all of twenty-seven.

It was his great victory to strip segregation of its moral legitimacy and in so doing, in a society like ours, to prepare it for its legal collapse as well. That he did this without holding office and in a way that a vast majority of white middle-class Americans did not consider threatening is a sign of his immense skill as a moralist-activist. Indeed, he was able to hold up for their inspection the very core of some of their beliefs and do it in a way that required them, rather than him, to pass judgment on themselves. In America today our racial problems are different and infinitely more complicated. Today every American city, be it northern or southern, seems to have a Martin Luther King Boulevard, and old enemies running for office casually invoke his name. But it is important to remember that when the movement that he led began, he could not drink at a southern water fountain, could not ride in most seats on a southern bus, could not eat at a Woolworth’s lunch counter, and could not use the men’s room in any facility along the highway. Not only could blacks not do these things, they could not do them in a climate that judged them morally and legally unworthy of any such ordinary actions.

In the years before he emerged as a genuine indigenous leader, that is, a native southern son on native southern soil, the leadership of southern blacks was minimal. There were few blacks, no matter how successful they were, whose positions were not in some way or another beholden to the white power structure. The undertakers (business would always be good) and doctors and dentists were successful and relatively free of white pressure, but there was not much leadership there. The old-time preachers, of course, were there and they had their followings, but in the past they had been poorly educated and had served more than anything else as safety valves for their communities’ emotions. More often than not they were burdened with the same doubts that weighed on the members of the congregation. Martin King was different; he was a scion of the new black South; throughout the South everyone knew King’s daddy and granddaddy, if not personally, at least by reputation. He was well educated and confident; he had been to a great university in the North and received a Ph.D. and in the process had found that white people were no better or smarter or more moral than he. He married a black woman who was equally proud and confident and well-educated. Martin, Jimmy Baldwin once wrote, “never went around fighting with himself like we all did.” Nor—as southern whites were now about to find out—was he alone; he was simply the most visible member of a new generation of talented, well-educated, utterly fearless young black ministers surfacing in the South. What distinguished him was the escalating Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott, of which he became the leader. It gave him first a great regional and eventually a great national platform and audience. The more the segregationists of Montgomery resisted, the more his pulpit grew and the more famous he became.

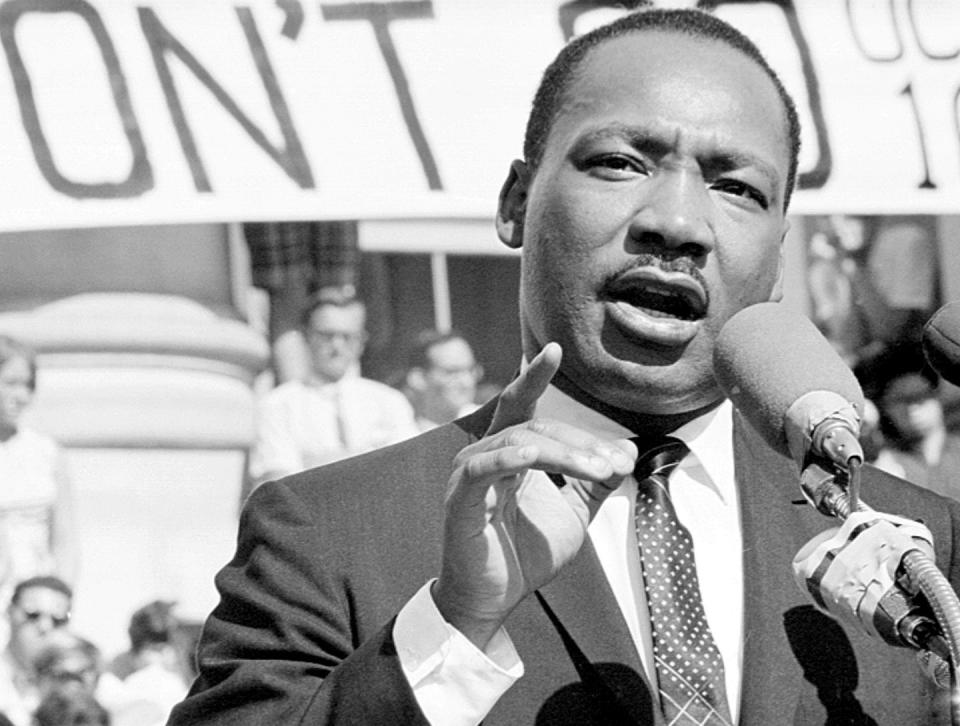

He did a number of critical things in those brief years. If the first thing was to give ordinary oppressed blacks of the South a sense of their own value, then the second thing was to force the white Christians of the South to confront their own beliefs. This was, after all, probably the most seriously religious section of the country. In the beginning he touched a generation of white ministers, forcing them in turn to confront their own congregations. But he was as much a man of broad politics as he was a man of the church, and his greatest victory was in turning the nation’s television networks into his personal pulpit. He and John F. Kennedy were the first great manipulators of modern political television, and Kennedy had several advantages over King: he was overtly in the political arena, he was white, and he was soon President. The years of King’s greatest success—from Montgomery in 1956 to the March on Washington in 1963—almost exactly parallel the rise of television in American homes as the prime new political conduit. When he began, we were effectively without true networks; when he had finished his greatest achievements, it was an accepted part of American political life that one campaigned for public opinion, as well as for political office, by means of television.

He did not do this as others did, by stroking journalists’ egos, by catering to our personal idiosyncrasies and offering us the small pseudo-intimacies that we cherish so much. In fact, he was not very good at traditional courting of the press. It was as if he was always a little too stiff, too aloof, too dignified. Instead, he offered reporters two absolutely irresistible things: ongoing confrontations of a high order and almost letter-perfect villains. In that sense he was more than just a master manipulator; he was, in the television age, as great a dramatist of mid-century America as Arthur Miller or Tennessee Williams. He cast his epics well; impoverished blacks would wear white hats and white police officers would wear black ones. He chose his villains carefully; they more often than not proved to be as primitive as their behavior was predictable.

So it was that without holding office he took a powerful existing social order and showed how it really operated and what the human price was. In effect, he took the terrible beast of segregation, which had always been there just beneath the surface, and made it visible. It was not so much that he slew that beast but that, instead, he brought it to the surface, and the beast, forced to reveal its police dogs and cattle prods and water hoses, exposed, died on its own.

It was classic media manipulation, and in subsequent years, as the immense impact of television upon our politics has become a central theme of our time, I have pondered the fairness of what he did. What he did, I am convinced, was more than legitimate, for the other side up to then had manipulated and coerced in its own way. The white power structure that owned all the television stations and newspapers in the South had over many years chosen not to listen to any legitimate black voices and not to hear the growing feeling of black protest. The white press of the South had never reported the thousands of informal meetings or the telephone calls the newspapers had received from mayors and police chiefs and judges and county attorneys and heads of chambers of commerce about what to cover and what not to cover and how best to deal with some local protest—protests that in the past had never become protests because they were never reported. The white manipulation that King was confronting existed in the form of a vast conspiracy of silence in virtually every town and city in the South.

Those early years brought his greatest victories. As he destroyed the moral legitimacy of segregation so too did the legal basis for it begin to come apart. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a direct result of King’s victories throughout the South. Part of his strength in those early years came from the absolute certainty of his belief. It was as if he believed so strongly in the essential goodness of America on this question that others must see it too, and in time his vision did become true.

Later in his career, as he turned to the North, he came upon harder times, and his leadership and his voice faltered. In the North the task was more complicated. It was no longer a problem of legal or political inequality: blacks had the right to vote. Rather, the problem was of age-old injustices becoming a hardened part of the culture and of the growth of a hard-core underclass. In the North the good old churchgoing blacks who trusted and abided and who had been at the core of his constituency did not exist. Instead, they had become bitter, alienated young blacks who saw the darkness ahead, who knew that the only job they probably had a chance at was as a parking lot attendant. They did not believe that the answer would come through love and goodness and nonviolence and Jesus Christ. They were the children of Malcolm, and King knew it.

The last time I saw him was in the spring of 1967. He was already speaking out against the Vietnam War, which cost him powerful allies in Washington and in the more traditional civil rights movements. He was trying to help organize various groups in northern cities without noticeable success. The simple evil of legal segregation, which had bound all blacks together in the South, was gone. The complexity of the problems in the North splintered the black leadership. The problem in the North, he told me one day, was what he called slumism—a bad job was a bad education was a bad home. He still gave the same soaring speeches, but now there was less community with the audience; and as there was less community with the audience, there was, I sensed, a greater interior doubt on his part. There was less resonance to his words. Martin King was, after all, a shrewd tactician and a shrewd politician, and I think he knew that he had come to the end of a certain era and that, from then on, the way of a moderate Christian was going to be much harder in this country.

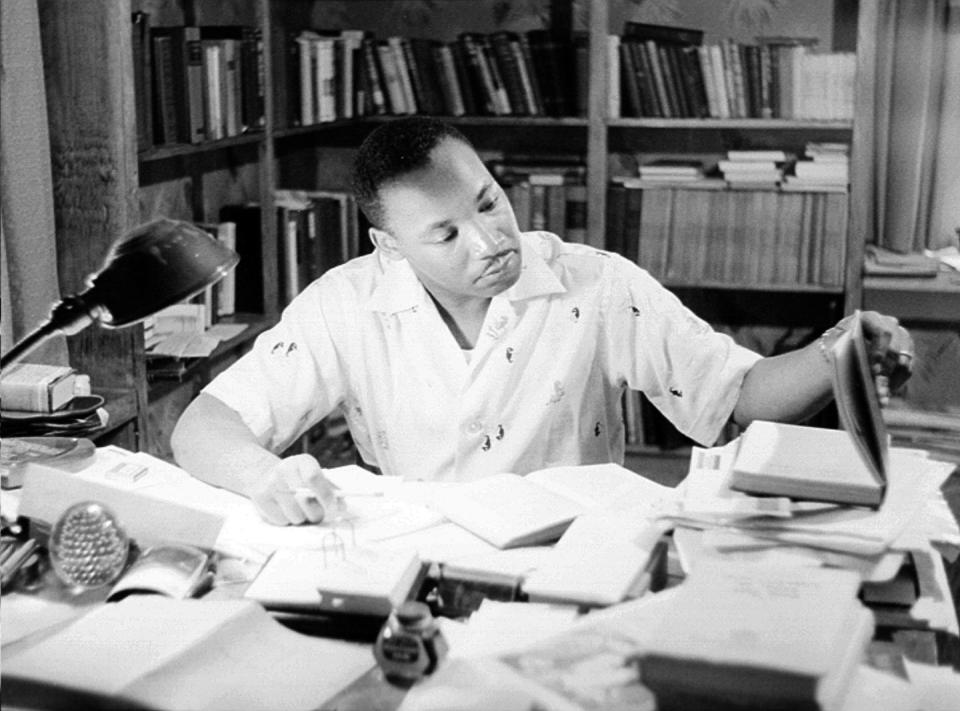

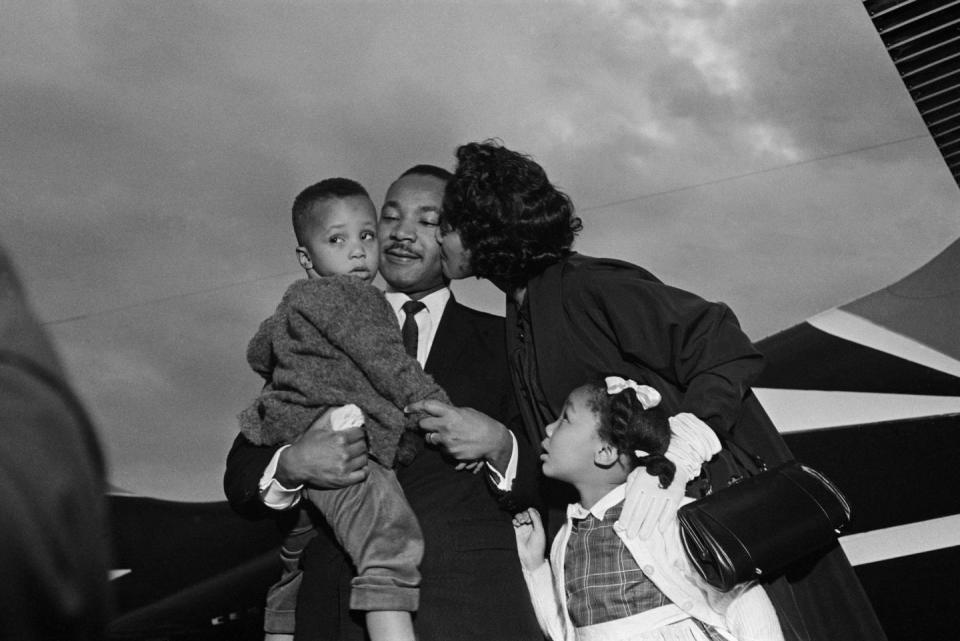

I was working on a piece about him at the time, and I came home after several weeks on the road to write it. When I was finished, I was satisfied with the piece—except that I did not have him. He had remained, as ever, personally elusive, formal, gracious but distant. It was as if any small talk or laughter might detract from the movement and might come at the expense of his own dignity, and thus the dignity of all blacks. (Because of that tendency, the younger black leaders in SNCC had always called him de Lawd. ) So I decided to give it one more shot, and I caught a plane to Atlanta; Andy Young took me to be with Martin and his family and many of their friends at someone’s swimming pool. He was more relaxed that day than at any time I had seen him before. I have a memory of a young King daughter hurting her knee and Martin going over and comforting her and giving her a piece of fried chicken. “Let’s put some chicken on that,” he said. “Yes, a little piece of chicken, that’s always the best thing for a cut.” In the background a photographer from Ebony was shooting pictures of the home of the wealthy black contractor whose pool it was. It was quid pro quo; the contractor always helped bail out King and his people when they were arrested; now they were giving the forthcoming spread in Ebony a little Nobel laureate class. I have since thought often of that gentle day, of Coretta King teasing Martin about what a poor dancer he was, of little black children running in and out of the pool, of how southern, how middle-class, and, finally, how American it all was.

You Might Also Like