How Marie Dutton Brown Changed the Literary World

When I approached Marie Dutton Brown’s Sugar Hill, Harlem brownstone on a recent Tuesday evening, I wasn’t sure what to expect - but I knew I had to look presentable. The iconic editor and literary agent is one of the most well-known and respected African American gatekeepers in the publishing industry. She’s a living legend who’s spent the past 50 years paving the way for marginalized writers and editors in an industry constantly trying to push us out.

And now, she’d invited me into her home.

As I reapplied my lipstick, a young man, also nearing the front door, asked me if I was supposed to be seeing someone. When I explained that I was meeting Brown, he asked if she was expecting me (Brown, as it turns out, gets a lot of unexpected visitors). The man indicated for me to wait on the lower level. Suddenly, a head peeked out from over the bannister, and a sweet voice exclaimed, "You don’t have to wait down there. Come up!"

Playing to type, Brown’s apartment is pleasingly filled with seemingly countless books; they're stuffed into shelves and piled high on tables, alongside pictures of her with legends like Ed Bradley Jr. and Walter Cronkite. Her cat Barbara came out of hiding to greet me. "She doesn’t do that often," Brown explained. "She must have sensed the good vibes." Before I knew it, the 77-year-old was offering me chamomile tea with honey and homemade lemon pound cake.

Brown sat across from me on her couch and started at the beginning: She’s the eldest of three children, born in 1940 to two teachers, one who taught English and the other civil engineering. After graduating from Pennsylvania State University with a Psychology degree within the institution’s School of Education in 1962, Brown taught junior high in Philadelphia and served as an education coordinator for the Office of Intergroup Education, an initiative throughout the Philadelphia public schools in order to teach children not to be bigoted through multicultural - the predecessor to the term "diverse" - curriculum.

Through this position, she met Loretta Barrett, then an editor at Doubleday. The rest was destiny: Years earlier, Barrett and Brown’s mothers had worked as schoolteachers at the same high school. So, in 1967, when Barrett came to an interservice training seminar where Brown was working to enhance the reading curriculum, Barrett encouraged her to reach out if she ever visited New York. Brown took her up on the offer later that year. After their lunch, Barrett asked Brown to come to the Doubleday offices the following day to meet with her colleagues. By the end of those meetings, Brown was offered an internship. She was 27 years old: "I thought, 'I could always come back to Philly but I will never have this opportunity to come to New York and work in publishing again.' Black people - we didn’t have those kind of connections. There was no access. So I decided to do it."

Brown moved with a friend to the Upper West Side in a $250-a-month apartment - a price I gasped at - and started at Doubleday the following month. She recalls her internship position as an "affirmative action hire" because she gained entry into publishing at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Back then, the goal was not diversity in publishing, but "multi-ethnic literature." During this time, most images of black people in textbooks were of slaves, and very few biographies and autobiographies of and by African Americans were being published. Brown hoped to change that.

At Doubleday, she worked under Zenith Books, an imprint geared towards African American youth. She was one of ten interns in her program - the only black woman, and one of only two who remained by the end of the year. Brown vividly remembers one cocktail party where an editor of another imprint at Doubleday called Loretta Barrett "a n*gger lover" while Brown was standing right beside her: "It was like someone had hit me over the head with a 2 x 4. Everybody looked at me. I said, 'I have to go.' The next day, the President of the company came to apologize to me." Brown told me that she believed that this was what we would call a "microaggression" today, but I pointed out to her that there was nothing micro about that experience.

Despite this racist moment, Brown persevered, and soon became Barrett’s assistant. She remained at Doubleday until 1969, then moved to Los Angeles, got married to an artist, and had her daughter (who followed in her mother's footsteps and is now a publicist at Hachette). While she was freelance editing in Los Angeles, two black women were hired to replace her at Doubleday, but both left because of the changing times - "the microaggressions," as Brown called them.

When Brown returned to Doubleday in 1972, she was told that "the black thing was over," and that she had to diversify her list with more non-black authors. In her words, "African American history and culture had diminished considerably. It was basically the category [of the books] and not the ethnicity or the racial identity of the authors. Many published African American titles, particularly [in] categories of history, sociology, and education, were being written by white authors. So, it was a matter of acquiring and publishing fewer books about the African American experience... [I wondered:] Were black people not reading anymore? Were black people not writing?"

At Doubleday, Brown worked with Marita Golden, Emeritus of the Hurston/Wright Foundation, scholar Mary Helen Washington, and Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, while bonding with other black editors and writers, such as Charles F. Harris and Toni Morrison, over drinks and phone conversations. She published titles like the Darden sisters' "Spoonbread & Strawberry Wine," Smart-Grovesnor's cookbook-memoir "Vibration Cooking," and Mari Evans's "Black Women Writers."

But despite this, Brown emphasizes that during that time, when black books became trendy, other editors would acquire books without taking into account their audience. Brown argued that many of the books coming out were dispersing information that black readers already knew about. "It was hard for many black editors," she said. "Many were hired at the time but they just left. They dropped out."

In 1982, Brown left Doubleday as Senior Editor, the first black woman to hold the position. "Doubleday was in the midst of being sold," she said. "The business of publishing seemed to be shifting and we editors didn’t know why. All these other editors were being offered other jobs but no one offered me anything. Having had candid discussions of job opportunities with several former colleagues, who had varying experience and success as editors at Doubleday, but were being hired throughout the industry, [combined with] my having multiple interviews and being asked to make presentations on marketing, et cetera, that I know others were not required to do, [I knew] that it was a matter of race."

But then an opportunity came along for Brown to become Editor-in-Chief of "Elan," a magazine for black women. She and her team only published three issues before the entire magazine was shut down. Afterwards, Brown became a bookseller at Endicott Books (now Book Culture), before her contacts, including her former mentor Loretta Barrett and a young African American associate editor named Gerald Gladney, asked if she would represent their authors.

In the 1980s, the proliferation of copy shops had begun. Unlike the sixties and seventies, writers were now making copies of their manuscripts to send to various publishing houses. Without agents to keep track of which editors had said manuscripts and which ones had interest, the responsibility fell on writers’ shoulders, which made for an unchecked and messy system. To fill what she saw as an industry need, in 1984, Marie Dutton Brown Associates was born. Brown evolved into a literary agent, reading and copying authors’ manuscripts, serving as a bridge between writers and editors, and always making a point to lift up the marginalized.

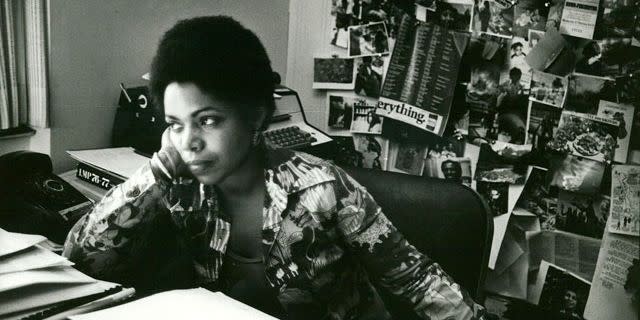

Back at her apartment, Brown proudly declared her dedication to black literature and identity. "I love my blackness. I stand up in my blackness," she said. Today, Brown is a one-woman machine, working from her home office, while shuffling interns, assistants, and aspiring writers - all of whom she considers her mentees - in and out of her brownstone. In the meantime, she is in the midst of writing her memoir. The woman never stops.

Before the end of our interview, she left me with sage advice: "I don’t compare myself to anybody," she told me. "Know what you like. Stick to it. Don’t always chase trends. You have to be fully exposed to what is going on where, and what you’re really interested in. Build on what you know - I’ve been really consistent in that."

Morgan Jerkins’s debut essay collection, “This Will Be My Undoing,” is forthcoming in January 2018 from Harper Perennial.

You Might Also Like