What We Lose When We Ignore the Real Roots of Murder Ballads

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When I first mentioned writing a podcast about murder ballads to people—spoiler: it actually happened, it’s called Songs in the Key of Death, and it’s out now—I would invariably get one of three responses. Most common: What’s a murder ballad? Then there was, oh, so like, “Goodbye Earl?” (Which, yes, but that song is about a made-up murder, and the ones in my podcast are about real events that inspired songs, as well as much, much older.) Or, finally, oh, so like Nick Cave’s Murder Ballads album? This line, in particular, was frequently paired with some mention of “Stagger Lee.” (Also, yup, but prepare to have your bubble burst on that song.) What took me by surprise, both as people asked these questions and as I researched for my podcast, was how much Black culture's influence is ignored despite its formative role in the genre.

Okay, so, what is a murder ballad? They are, of course, a sub-genre of ballads, which are poems and songs, that go back much further in history than we will travel here—you can get your 17th century Europe kicks on another part of the internet. And while they can be about the death of anyone, historically, the variation of the format that became the most popular in our culture is murdered girl ballads (think of songs like “Delia’s Gone” by Johnny Cash, “Omie Wise” as performed recently by Okkervil River, or Eminem’s “Kim.”)

These works frequently moralized and idealized behavior for women. They are all about a woman or girl killed for some transgression and come in broad themes like drowned girl ballads, cheating wife ballads, a woman who got pregnant out of wedlock ballads—generally any behavior not condoned by the patriarchy or the church, which were, of course, the same. The point was to make it clear to everyone that stepping out of your expected gender role or the rules of society would be met with severe punishment, often death. People repeated these stories to keep that message alive, and to keep women powerless. But dead women weren’t the only people about whom murder ballads were written, and America isn’t the only culture to favor them.

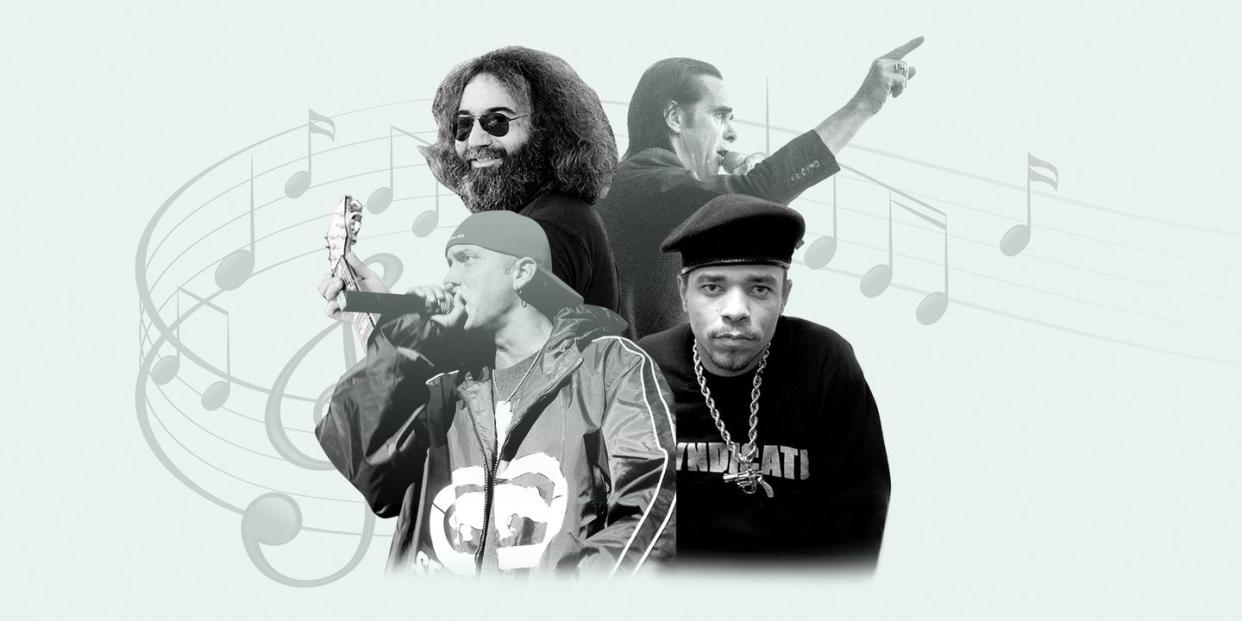

The genre first became popular in the oral tradition in Britain, Ireland, Scotland and Scandinavia in the 16th and 17th centuries. (“Henry Lee,” one of the saddest and most beloved songs from Cave’s album, sung in duet with PJ Harvey, is an interpretation of a song that actually originated in early 19th century Scotland.) When those predominantly white and European people immigrated to America, they landed in the Appalachian region, planting roots in New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, the Carolinas, Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee. That tradition came with them and those stories, handed down for generations, were meticulously collected by European historians, the most significant among them being Francis Child, whose collection of ballads is the backbone of the folk tradition in Europe and America. But just because Europeans were the most prolific documentarians doesn’t mean they invented the practice. The notion of singing to carry a story or retain a memory is a practice widely known among African, Indigenous, Asian, and Hispanic cultures worldwide.

Which brings us back to “Stagger Lee,” which happens to be the focus of the final episode of Season One of Songs in the Key of Death. Cave’s take on the well worn legend is notable for its explicit and violent lyrics, warping a bar fight-turned-deadly to the furthest extreme and trading in the insults of toxic masculinity. But when you hear Cave singing “Stagger Lee,” who do you imagine Stag is, in your mind’s eye? If you’ve watched Peaky Blinders and listened to the cut, as well as heard Cave’s “Red Right Hand” which serves as the TV series’ theme song, you might imagine it’s some turn of the century, white gangster covered in soot, not unlike Thomas Shelby and his band of brothers. You would, however, be wrong.

Lee Shelton, a.k.a. “Stack Lee,” was a real guy who killed another real guy, Billy Lyons, after a fight in a bar in the “Bloody Third District” of St. Louis in 1895 on Christmas night. They were both Black. The person who originally wrote the song is thought to have been a Black troubadour, one of many prolific songwriters who were the heart and soul of the ragtime music movement exploding in the city, a scene from which white songwriters liberally and brazenly stole to create pop and big band music.

The version of the song Cave sings is taken from a book of toasts passed among Civil Rights leaders in the ‘60s, written expressly to be performed in exclusively Black spaces and lionize Stack Lee as a Black folk hero. When white people co-opt the song, the Blackness inherent in it is stripped away. It becomes colorless, and removed from the context in which it exists, in part to better appeal to white audiences. That’s nothing new; the song has been passed from Black to white audiences for generations as the Clash, the Grateful Dead, Jerry Lee Lewis, and even Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger have each adapted it into counterculture scenes for consumption by, primarily, politically left-leaning white audiences.

That the legend would divide in music between Black and white audiences and creators is no surprise when you consider how the record industry segmented itself in the early 20th century. Before record players, people went out to hear music. They went to interracial bars and clubs that sometimes doubled as bordellos, exclusively white clubs, or juke joints for Black audiences—and a lot of people were listening to music on jukeboxes in lunchonettes, diners, bars, wherever. Sheet music was where artists made their money. But education for the Black population was, at the time, still sparse, so there weren't a ton of Black lawyers and managers, or even swathes of highly literate Black members of the population, to explain to artists of color that they should copyright the broadsheet ballads they were selling so as to avoid having them stolen by white musicians.

Record players became a thing in the late 1870s, and by 1895, when Stack killed Billy, they were mass-produced. To convince people to buy them, companies like RCA and Victor soon figured out that they needed to press some vinyl for people to play. (Welcome to the origin story of record labels.) Under a social rule of separate but equal, music for white audiences was performed by white people, sold in white record stores, and filed under white genres like pop, hillbilly/country, and big band. In contrast, Black music was segregated, and filed into race records like jazz, bebop, and ragtime. Songs written across color lines could be adapted and repackaged across audiences, but in stores and later on radio, genres remained separate both because it was the law of at least part of the U.S. and so advertisers could then reach their preferred audience.

We lost much when capitalism enforced segregation to the point of turning it into folk tradition. Namely, the truth. Murder ballads are part of Appalachian, hillbilly, and country music traditions. But they also exist in blues, spirituals, and slave song traditions. It's wrong that no one mentions TLC’s “Waterfalls” or any of the prolifically violent body of work from the gangsta rap era when murder ballads come up. Instead, Ice-T still faces derision for writing a song from the point of view of someone who is fed up with abuse from the police but Johnny Cash is a hero for singing the lyric, "I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die." ("Cop Killer," an excellent protest song, is still unavailable to stream because it’s considered too incendiary.) Murder ballads have collectively come from Black and white cultures to paint pictures of small segments of society, to memorialize important events, and to pass along the legends of crimes. Until that becomes widely accepted, our view of the genre is incomplete.

You Might Also Like