Loretta Lynn Made the Mundane Incendiary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

“Well here’s the story of my life, listen and I’ll tell it twice,” wrote a 27-year-old Loretta Lynn in one of her earliest compositions, “The Story of My Life.” How the young singer, at that point still working barrooms in rural Washington logging towns, could foretell that her story would become one of the best-known in popular music history is hard to know. What is clear from that 1959 chronicle, though, is that her story’s prevailing themes were already obvious: she described Kentucky as a “paradise,” and motherhood with a raw quip: “Got kids of four, and I’m tellin’ you I don’t want no more.”

When we try to define what country music is, what could possibly tie together a genre with such wide aesthetic variance and complex history, those two occasionally contradictory arcs—nostalgia for some mythic, bygone rural idyll paired with unapologetic candor and sharp observation—more or less sum it up. When we’re looking at Loretta, we are indeed looking at country, and that should have been obvious to everyone from just about the moment she got to Nashville and immediately befriended Patsy Cline.

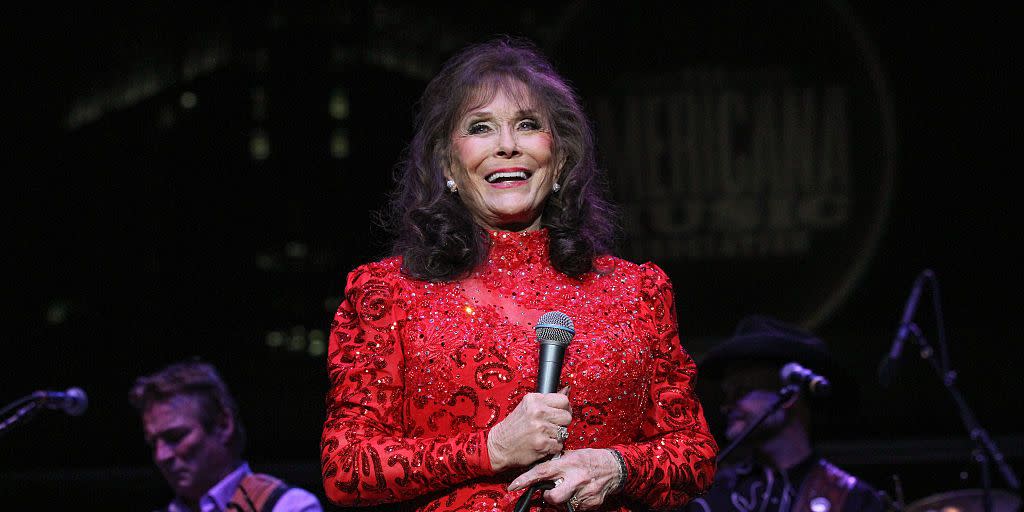

Six-plus decades and 50 albums later, Lynn is gone, having died at 90 on Tuesday at her ranch in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee. With her goes a singular, irreplaceable cornerstone of country music history that every artist and, especially, every woman artist has built upon as they seek to channel that same pair of inspirations. There was no big picture angle or mission to Lynn’s work besides telling her story over and over and over again with the kind of honesty and wit that made it feel not just fresh but revolutionary, every single time.

Or as she put it, “I’m not a legend, I’m just a woman.” For those that would laud Lynn as a trailblazer, she was. But her inventiveness was in bringing the kind of plainspoken women’s wisdom that had long flourished on country and folk music’s margins to the big stage; she wasn’t the first, but she was original in her verve and confidence—and had one of the most powerful voices in country music history, ensuring that she was both heard and remembered. Simply by singing her truth, Lynn completely remade the genre in her own image.

Lynn’s early years are the most familiar, thanks to her own frequent chronicling of Butcher Holler, Kentucky and its environs. “It was a lot sadder than what it looked like on film,” Lynn would say later—but the rosy nostalgia that colored “Coal Miner’s Daughter” (the song, book and movie) still helped consolidate a kind of rural pride that pervades country music to this day.

Self-mythologizing, even to the point of eliding her true age to make her early marriage and musical savant status more impressive, served an important purpose. Like Kitty Wells before her, Lynn backed up her challenges to the status quo with an unimpeachable backwoods pedigree and bone-deep domesticity, having had four of her six children and been married over a decade by the time she first saw fit to write that early story of her life; to be fair, she’d already lived a lot of it.

When a world-weary Lynn arrived in Nashville almost a decade after Wells’s surprise hit “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” supposedly opened Music Row to women, she still faced considerable skepticism. Cline was the only woman in town, as far as record executives saw it; women artists were considered such a liability that few songs were written with female singers in mind.

Luckily, Lynn had long since been writing her own. What was first a creative outlet for a homesick Blue Kentucky girl became the linchpin of her success, both a necessity given the dearth of good material and a pleasure. “There ain’t one thing in life that brings me as much joy as writing,” Lynn wrote in the introduction to her recent anthology of songs, Honky Tonk Girl: My Life In Lyrics. “I’d rather write than sing.”

It took a few years after her Nashville arrival for both her songwriting style to come into focus and the industry to catch up with her, but there were glimpses of the radical self-assurance that would define her signature hits. “Two Steps Forward,” a deceptively peppy ode to the challenges of leaving a bad relationship, previews the brasher tone of her mature work, as does “Night Girl,” a candid rebuke of would be sugar daddies. (Also, “You were born into a wealthy family/I was born into a world of poverty” is more cogent than 90% of what’s on country radio today.)

No surprise, then, that her greatest success came once her label, Decca, finally started releasing her own compositions as singles. “Dear Uncle Sam,” a folksy, functionally anti-war lament (“I really love my country, but I also love my man”), started the avalanche of hits in 1966; “You Ain’t Woman Enough” hit No. 2 on Billboard’s country chart that same year, and then “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ On Your Mind)” flew up the charts, becoming not only the 7th ever No. 1 Billboard country song recorded by a woman, but the first written and recorded by the same woman.

What “You Ain’t Woman Enough” had hinted at—a kind of femininity that embraced confrontation in place of moping and handwringing—“Don’t Come Home” shouted from the rooftops, giving Lynn her first taste of controversy alongside then-unprecedented success. Clear to both Lynn and her label was the fact that the song’s success could be at least partially attributed to the listenership of women who heard themselves in its almost uncomfortable honesty. It’s hard not to cringe when Lynn sings, “You come in a-kissin’ on me/It happens every time,” thinking about how recently that expectation, of women as living sex dolls for their male partners, was the norm.

Those two songs marked a turning point for Lynn, and for country music: The irrevocable acknowledgement that women are a credible country audience and deserve to be taken seriously in the genre (and all genres). No surprise, then, that Dolly Parton’s first charting single, the similarly bold “Dumb Blonde,” followed hot on the heels of “You Ain’t Woman Enough”—Lynn helped usher in a spate of country songs about women staring down their adversaries, standing their ground and even threatening to make good on some violent promises, carving out space for women artists and listeners in the process.

That was what it took, frankly. Sexism in country music was impenetrable enough that being exceptional, as Lynn was, was not enough. Only after Loretta told the country industry she’d take it outside—and found they absolutely loved Fist City—was she able to find sure footing on Music Row. (“I’ve been in a couple of fights in my life,” she mentioned oh-so-casually in Coal Miner’s Daughter, which opens with the perfect sentence, “I bloodied my husband’s nose the other night.”)

It is hardly a reach to explain that before there were any “outlaws” in country music, there were the genre’s women, who challenged every Nashville status quo simply by making music in the first place. Lynn took that knowledge and ran with it, careening through barriers instead of delicately trying to hop over them—and skillfully capitalizing on her “bad girl” reputation once she’d earned it.

Almost without exception, her most successful songs were her most provocative, which she had surely noted by the time she released “The Pill” in 1975. The first single she put out after being named the Country Music Association’s first woman Entertainer of the Year in 1972 was “Rated X,” a tawdry ode to the challenges of life as a divorcée (“Why us women don’t have a chance,” she says frankly as the song fades out). There is an easy parallel to be drawn between Lynn’s rise and the ascendance of the women’s liberation movement. She saw it, too: “This woman’s liberation, honey, is gonna start right now,” she quipped on 1973’s “Hey Loretta”—whose lyrics also include, “Instead of loving just one man, I’m gonna love ‘em all.” It was undoubtedly strategic to toy with these taboos, and yet it was just as undoubtedly honest and true. After all, they wouldn't have rattled the earth if they weren't.

Yet there was a divide between the Lynn persona, in which she teased free love and casting aside hapless husbands, and Lynn’s reality. She remained married to Doolittle Lynn from the age of 15 until his death in 1996, all while candidly discussing his abuse and alcoholism. To whatever degree her songs present a progressive politic, it wasn’t borne out at the polls: She stumped for George H.W. Bush and Donald Trump.

Her radicalism was a personal one, hinging on the observations of one very tired wife and mother who could depict in intimate detail the dual weights of poverty and systemic sexism. To bear witness to that specific experience on a grand scale not only invented a specifically feminine perspective in popular country music, it also seemed to give the entire genre a dose of truth serum. Lynn’s sharp wit and pointed takes made some of her peers’ pop shlock look even fluffier by comparison, paving the way for more clear-eyed country songs to come.

For Lynn to pass now, as women’s bodies and our autonomy are once again front page news, adds an extra degree of potency to the candor and nonchalance with which she discussed women’s sex lives in song. “I knew that song was gonna be big,” Lynn said at the time. “Why, everyone takes The Pill these days—there’s nothing dirty about it.” That pragmatism has always been so rare in popular music, and yet incredibly necessary; every movement needs its anthem, and whatever her own voter registration card looked like, one of the most important artists in country music history made an anthem for every woman who wanted the choice not to be pregnant—a choice that is still far from secured.

She rejected labels like feminism and women’s liberation while also rejecting the gender orthodoxies that she saw as fundamentally impractical—one of which was women not having a place in Nashville. That certainty and self-assurance in a world that told her she’d be much better off cowering in fear was what allowed Lynn to completely reshape the genre, to write a new blueprint for women country singers and a slew of timeless songs for them to use as a jumping off point. It speaks to the continuing necessity of her work that so many of those songs are still rarely covered, too aggressive and provocative even now to be deemed crowd-pleasing.

In a genre where women had too often been relegated to being either chaste maternal figures or wily honky tonk angels, Lynn made a new archetype—one that was relatable to a great deal more women than either of the previous ones. “I know what it’s like to be pregnant and nervous and poor,” as she put it, before singing yet another song for all the pregnant, nervous and poor women she knew were listening. It’s hard to even name a true heir to her legacy, one that has ascended to the same heights while perpetually poking Nashville’s bear—surely an indictment of the contemporary country industry, but also a testament to the pure, impossible-to-misinterpret nature of her provocations.

We are lucky “to live in a time where Loretta Lynn songs have always existed,” as Madison Vain put it in the anthology Women Walk the Line. Perhaps we’ll be lucky enough to see someone take up the mantle of those songs in her honor, exposing the clear truths that country, and popular music, would rather ignore through bright, swinging, addictive music.

You Might Also Like