The Long and Happy Life of Maida Heatter

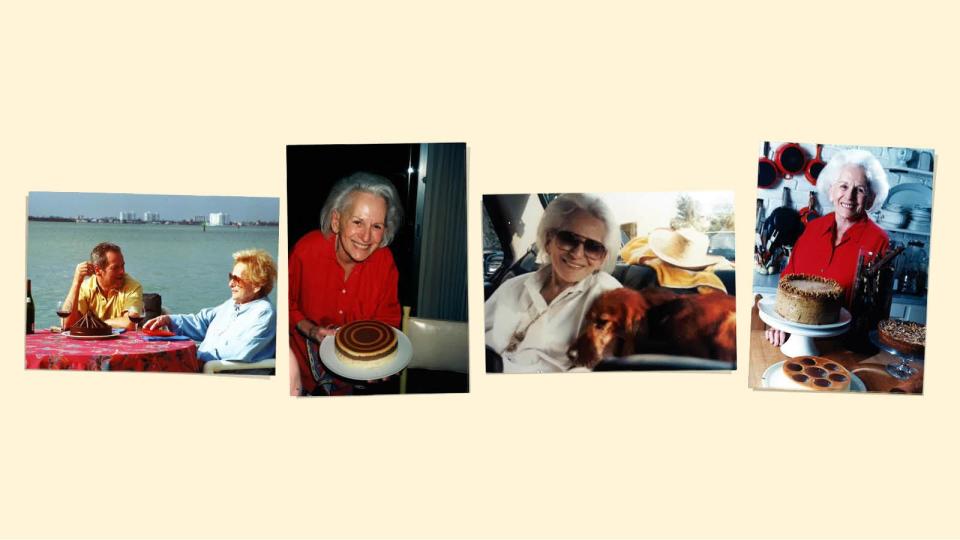

Maida Heatter always had brownies in her bag. Or biscotti. Cookies. You know, the portables. She handed them out to her mailman, people she ran into on the street, new friends, old friends, Wolfgang Puck. She flung brownies filled with York Peppermint Patties off the stage at the James Beard Awards in 1998 wearing Versace and a mischievous grin. Sharing her baked goods—straight from her bag, or through her recipes, published in nine cookbooks during the 1980s and ’90s—was the whole point. A self-taught baker, she became a household name, charming audiences with her saintly halo of white hair, her foolproof layer cakes, and her real-talk recipe instructions. Her recipes went pre-internet viral and inspired many of our current queens of desserts, including Dorie Greenspan, Alice Medrich, and Christina Tosi.

Heatter passed away at 102 this week in her Florida home. For the past few years, she spent most of her day resting in bed. This spring, her final cookbook, Happiness Is Baking—a compendium of her most beloved recipes pulled together by Maida’s niece and caretaker, Connie Heatter—came out from Little, Brown. The writing is Maida’s, tightened and updated here and there from previous books, but there are no new recipes or reflections on a life long- and well-lived. Sadly, Maida didn’t even seem to know the cookbook existed. That’s what Connie told me when I spoke to her recently. She had shown Maida the bright red cover with her name in big yellow letters, but there was no recognition from the baker.

What was Maida’s final cookbook was the first for me. I admit I didn't know much about her, but the sass, vibrancy, and utter delight in life that radiates from her words pulled me in immediately. I wanted to find out what Maida Heatter was really like, behind the sugarcoating. So I searched for her voice in her cookbooks and past interviews, and tried to paint my own memory of the queen of desserts.

The Palm Beach Brownies

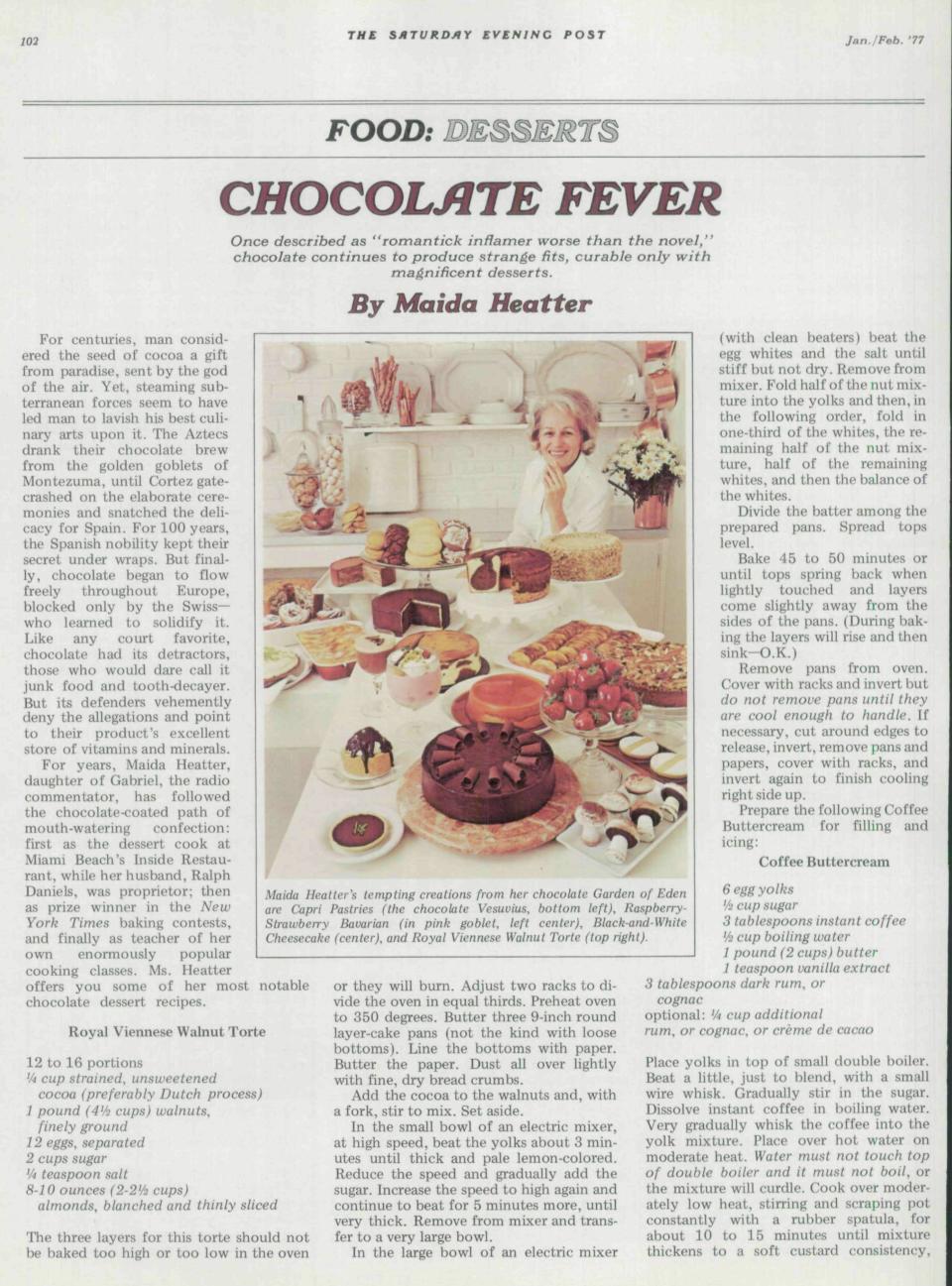

Maida Heatter grew up in New York on Park Avenue, the daughter of radio commentator Gabriel Heatter. Her mother, Sadie, was a wonderful cook and Maida’s biggest influence. Maida studied fashion illustration at Pratt and was soon illustrating scarves and designing jewelry. If you come across a pair of vintage David Evins pumps, the loopy logo with circle-topped i’s is Maida’s handwriting. She eloped with Evins in 1940. In the newspaper announcement her father is quoted: “He’s a fine fellow and it’s all right with us.” They divorced five years later. Always, Maida was baking at home and begging restaurants for recipes, amassing a collection that would make up her first books.

She married again and moved to Miami. She divorced again and remarried once more. According to lore, when she met Ralph Daniels, a retired pilot and “tall, rangy Texan,” she reached into her pocketbook and offered him a brownie. “That’s what did it for him,” Heatter said.

The Palm Beach Brownies were Maida’s mascot. The recipe originally came from a deli in the ritzy Florida town, but she’d tinkered with it over the years. “People have told me that when they hear my name, they associate it with that one recipe,” she said on NPR in 1998 before adding that she had some in her pocketbook.

“Open a coffee shop,” she told Ralph, “and I'll make brownies, and you can just read the newspaper and pour coffee.” In the early 1960s they opened Inside, a café in Bay Harbor Islands. Maida baked the restaurant’s dozen daily desserts in their home kitchen, and Ralph carefully transported them “either by car or boat,” an arrangement that lasted about a decade.

Her local baking reputation grew. Friends, neighbors, and restaurant patrons asked for copies of recipes. She taught cooking classes and sold Palm Beach Brownies to the Jordan Marsh department store, packaged in a white box with a copy of the recipe. She gave up the brownie business when she started writing cookbooks. “But it was wonderful while it lasted,” she said.

The Elephant Omelet

In the myth of Maida, there is one event that set the course of her career: the elephant omelet. Made with real elephant meat, canned (that she bought from a warehouse in New Jersey), for a 1968 Republican convention stunt menu item at Inside. No one even ordered the dish—which is too bad; it was pretty good, she told the Miami Herald—but the story spread, and the New York Times sent food editor Craig Claiborne down to Florida to investigate.

“Craig thought he was coming to my house for an elephant-meat omelet,” Heatter told the same paper more than a decade later. “He didn’t know he was coming to see my desserts. I had about 30 cakes on the table—the most impressive things I could arrange.” When he asked for one of the recipes and saw her extensive files, he was “bowled over.” “You should write a cookbook,” he told Maida. So she did.

Maida baked 12 to 14 hours a day in a kitchen that hadn’t changed since she designed it in the 1950s. She had a clear view of Biscayne Bay. Two eye-level Thermador ovens held court. The layout was open before open kitchens were the norm. The trusty Sunbeam stand mixer was always at the ready. She’d bake in pull-on pants and men’s shirts from the J. Peterman catalog.

A driven, ambitious, meticulous Virgo, Maida churned out that cookbook and mailed it to a publisher in a big heavy box. She received a $5,000 advance for Maida Heatter’s Book of Great Desserts, a hardcover with 416 pages, nearly 300 long and conversational recipes, and 35 pen-and-ink illustrations by her daughter Toni Evins, which was published by Knopf in October 1974. On the cover, Maida grins behind a table filled with cakes, cookies, and other groovy treats. It might be a smile of relief: She had to rebake every recipe when she found out her oven was 35 degrees off.

In a short piece about the book, Claiborne called her “one of the world’s best home dessert makers.” A great compliment, but also a slightly condescending one: home. Like a pat on the head. The book became a bestseller, and Maida was 58—her career just taking off as those around her were retiring.

By the time she turned in a manuscript for one book, she was keeping files for the next, and her second soon followed: Maida Heatter’s Book of Great Cookies, 1977. In 1980 came Maida Heatter’s Book of Chocolate Desserts, which was a smash, selling 100,000 copies the first year. Her recipes ran in Bon Appétit, Gourmet, The Saturday Evening Post, and Ladies’ Home Journal. In 1980, Woman’s Day ran a fabulous spread of chocolate cakes, glistening like Fabio, set on a damask tablecloth. In 2002, Saveur dubbed her the Queen of Cake—and it stuck like cocoa powder on one of her mushroom meringues.

The East 62nd Street Lemon Cake

One of the first recipes she published in the New York Times, with Claiborne’s encouragement, was the East 62nd Street Lemon Cake (named after her daughter’s New York address; she was the originator of the recipe). The crust is crisp from the lemon-sugar glaze, the cake inside unbelievably moist and lemony. It’s been a sensation since it originally ran in 1970, Margaux Laskey wrote in a Times look back about the cake.

You can get a sense of Maida’s attention to detail in that recipe when she makes sure it comes out of the Bundt unscathed by buttering and coating the pan in breadcrumbs. Pie crust instructions run five pages. Recipes include addresses of stores where you can source chocolate by the ton, sugarless cider jelly from Vermont. Notes explain why you should buy whole dates instead of diced. Each recipe promises to be the best of your life. (Maida is a study in self-promotion.) Joe’s Chocolate Fudge Pie “creates ecstasy.” Cookies called Tulipes that look like taco salad bowls are “the height of swank and elegance.” Date-nut spice cookies have a “perfume during baking [that] can turn strong men into pussycats.” “Have your camera ready for this” Mile-High Cinnamon Bread.

Whether they live up to their promise is in the eye of the cake-holder. A Washington Post reporter in 1982 felt them overhyped, writing, “Having tested over a dozen of the desserts, we found only four of them uniquely delicious, the rest perfectly good and attractive, but nothing that would send us begging for the recipe.” When the writer confronted Maida about it, she replied: “I do exaggerate.” And what’s so wrong with that?

Skinny Peanut Wafers

“Everything Maida Heatter touches turns to high calories,” wrote Suzy Kalter in People. Nearly every early interview with Maida brings up her diet, her weight, how many pounds she’s gained or lost, how many pounds Ralph gained by simply being in her presence. From those pieces I know Maida swam, ran on a treadmill, and worked with a handsome trainer named Jean-Claude who loved her Skinny Peanut Wafers. She ate a high-protein diet to lose weight, had only one bite of dessert at restaurants, and tended to yo-yo diet. She seemed reluctantly aware of her body—but perhaps only because everyone else seemed to pay so much attention. One article ended with this cringeworthy line: “The Today Show was still several days and 17 pounds away.” Still, she never bent her recipes to the diet trends of the time.

Maida approached exercise as diligently as her baking, but “I hate everything about it,” she told a local reporter in 1998. “When I get on the treadmill I always say, God I’m so bored. This is what willpower is. Nobody’s going to know if I get off and go into the kitchen and have a cookie. But I stay on it.”

Multigrain and Seed Biscotti

“Ah, there’s good news tonight,” was Gabriel Heatter’s on-air radio introduction during World War II. During one of the darkest times, he squinted for light. Maida Heatter did the same. “I’ve had a few problems in my life, but what to do with cookies has never been one of them,” she writes in Maida Heatter’s New Book of Great Desserts. When her mother died in 1966, her father moved in with the Heatters until he died in 1972. After a massive stroke, he needed constant care from Maida, who never left him home alone. In between looking after him, she baked.

Then in 1989 Maida’s daughter Toni died in a glider accident in Colorado. Two years later, her husband Ralph died of cancer. Heatter’s writings never gave away her grief. After Toni’s death, she spent some time in Maine where her niece Connie told me she “walked around like a zombie.” After Ralph’s death, she went to Canyon Ranch in California, where she came up with a recipe for Multigrain and Seed Biscotti. Her Brand-New Book of Great Cookies was published in 1995, her first book since losing them both. It opens, “Happiness is baking cookies.” She illustrated it herself this time, in a similar style to Toni’s, but with more cross-thatched shadows. Her friend and neighbor Hope Fuller told me “she never talked about anything sad.”

“I am so lucky, I can’t tell you,” Maida told the Miami Herald in 1997. “I know women my age who are bored. [She was 81 years old.] They have nothing to do. Even if they have family, their families are somewhere else—their kids, their grandchildren. I really don’t [have family]. But I always have so much to do, even if it’s that I’m going to go into the kitchen to bake a cake. I’m in seventh heaven—I’m having so much fun, and it doesn’t matter if I give it to the mailman...When you’re busy and you’re being creative, that’s something the outside world can't compete with.”

The September 7th Cake

In 1986, Maida wrote a letter to the editor in the New York Times. “Your story on artists and old age broke me up—and I cried. Do you remember when they asked Churchill how it felt to be 86 years old? He answered, ‘In lieu of the alternative, it feels pretty damn good.’” She was 70 then and only a decade into her cookbook career. That’s one hell of a way to spend your golden years.

In Maida Heatter’s Book of Great Chocolate Desserts there’s a recipe for September 7th Cake, named after her birthday to ensure its perennial appearance. (She had it on her 102nd birthday surrounded by a few close friends and family, Connie told me.) It’s a flourless chocolate soufflé-like layer cake with a gelatin-bound whipped cream filling and coffee-chocolate whipped cream icing. It's texturally playful and a celebration of fluff—whipped cream, two ways! But it's a complicated recipe, meticulously constructed and labor intensive.

Despite her hustle, Heatter’s always perceived as this sweet old lady in Florida who bakes polka-dot cheesecakes. She wasn’t a studied pastry chef with French training; she was just your friend. And it’s easy to dismiss that, a blip in American cooking history as cute as a dated sitcom that plays late at night. But hopefully we don’t. Because sometimes the influence of friends is far greater than the influence of strangers in tall toques.

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit