Long Before The Devil Wears Prada, This Iconic Movie Pulled Back the Curtain on the Fashion Industry

Looking back on 1994, the year of InStyle's birth, if I were to choose another event that had a lasting impact on the world of fashion, it would have to be the Christmas Day release of Robert Altman's trussed-up turkey of a film, Ready to Wear.

Surprised?

Offensive, overwrought, and just plain obnoxious, the cinéma à clef nevertheless managed to strike a nerve with its paint-by-numbers stereotypes of industry insiders, from the pretentious designer (Richard E. Grant) to the sleazy photographer (Stephen Rea) to the brainless TV fashion reporter (Kim Basinger). The movie critic Roger Ebert, referring to a running gag in which the characters, while doing the rounds of Fashion Week, literally step in excrement, began his review with this gem: "The truth is, there is a lot of doggy-do in Paris."

Likewise, the movie stank. And it also stuck. Despite its dismissive tone — even the title had been dumbed down from Pret-a-Porter at the last moment — Altman's attempted roast of the fashion world and all its absurdities inadvertently revealed a simmering societal distrust of the apparel industry that would, 25 years later, erupt into a full-blown revolution. Witnessing the great changes sweeping through the industry today, as the important stakeholders race to embrace ethical standards thanks to consumers' holding them accountable for their actions, the sort of fashion immorality and comeuppance portrayed in Ready to Wear — the vicious editors squabbling over a photographer and rival critics falling into bed with one another — now seems rather quaint.

"Paris fashion," says Basinger's Kitty Potter in one scene, "is a thrilling bore."

But at the time, fashion was exactly that: a big, glamorous, colorful business, not just yet the mega-industry that would become defined over the next decade by giant luxury conglomerates and globalization. The curtain hadn't been pulled back all that far for the general public to see, not in the way The Devil Wears Prada would do more than 10 years later. And Ready to Wear only hinted at the tension of that somewhat innocent, somewhat cynical time, as the lines between the mainstream and the elite were beginning to blur and the term "luxury" was naïvely being applied to almost anything, from cups of coffee to computers.

In retrospect, 1994 seems like a turning point anyway, when designers were becoming more attuned to the importance of public perception, for better or worse. The ravages of the AIDS era were starting to fade, yet drug abuse was on the rise within the industry and the glamorization of "heroin chic" was on the horizon. In fact, something of a tug-of-war was happening behind the scenes over the aesthetic extremes, between glamour and grunge.

In fashion a backlash was brewing against the prevailing (and commercially disastrous) "waif" look, and there was a concerted call among editors and retailers for a return to a classical sense of beauty, as documented by the acclaimed journalist Amy M. Spindler in The New York Times that year. The editors of Vogue and Harper's Bazaar, she revealed, had specifically pushed retailers to buy into red lipstick, diamonds, and more romantic designers like John Galliano in response to frustrated readers and concerned advertisers.

"It explains why the model Kate Moss, in her usual position reigning over Times Square in a Calvin Klein jeans billboard, suddenly looks a lot less like last year's waif and a lot more like Patti Hansen circa 1978," Spindler wrote.

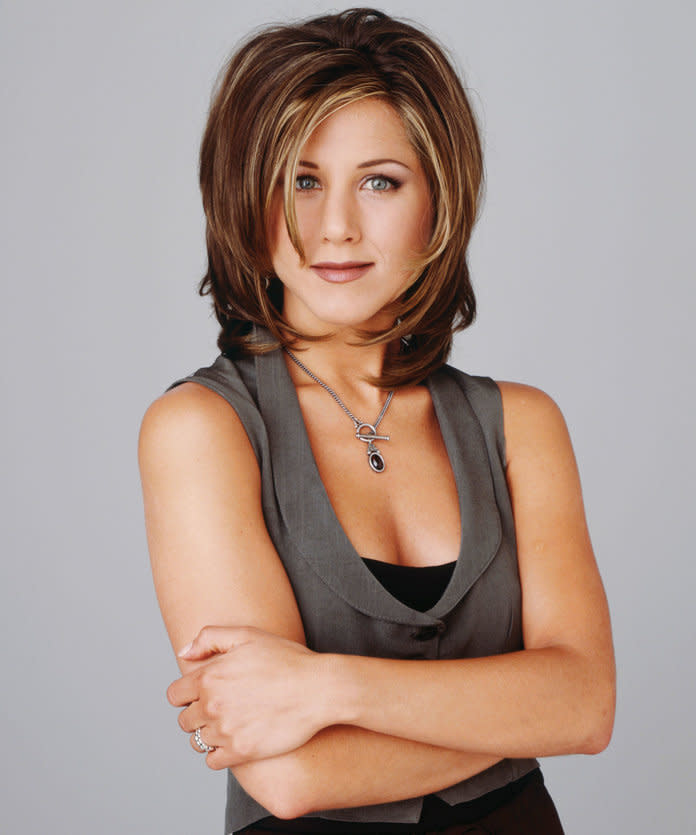

On television, Friends arrived with its sunny, optimistic view of young urbanites, featuring Jennifer Aniston's trend-setting character, Rachel Green, who would go on to work for Ralph Lauren. And on film there was the Gen-X glass-half-empty angst of Reality Bites, with Vickie Miner (Janeane Garofalo), who considers a promotion to a manager at a Gap store a high-water mark in her career. The show My So-Called Life offered a glimpse into the psyche of a high school antihero like Angela Chase (Claire Danes).

It was a year of surreal moments and sometimes startling contrasts. Kate Moss and Johnny Depp became a couple. Lisa Marie Presley married Michael Jackson. Prince Charles and Princess Diana confirmed their respective affairs. Sassy ended. InStyle began. Jackie Onassis, high priestess of glamour, died. Kurt Cobain, of grunge fame, committed suicide. Much of 1994 wasn't pretty, not Tonya Harding or O.J. Simpson or Lisa "Left Eye" Lopes, who set fire to a pair of sneakers in Andre Rison's Atlanta mansion and burned it to the ground. And yet these moments still resonate despite the fact that pocket-size cell phones were just becoming popular and most newspapers did not yet have websites.

Even before the dawn of social media, all the howling that ensued over Ready to Wear, both inside the industry and out, reflected a sentiment that seems as true today as it did then: People may love to complain about the absurdity of fashion, but they also love the absurdity. It's not for nothing that Altman's movie included a runway show where the models wore nothing, and that one, at least, was deemed a critical success.

For more stories like this, pick up the September issue of InStyle, available on newsstands, on Amazon, and for digital download now.