You’ll Want to Pay Close Attention at Loie Hollowell’s New Show

It’s commonplace that art—painting, especially—rewards close looking. “To see clearly is poetry, prophecy, and religion, all in one,” art critic John Ruskin wrote in 1856. Still, in American artist Loie (pronounced “Low-ee”) Hollowell’s case, it’s urgently true. On her intricately layered canvases—built up into three dimensions, in some areas, using a mixture of sawdust and high-density foam—expressions of the agony and the ecstasy of being a woman beget a delightfully complex viewing experience.

This weekend, Hollowell helps to inaugurate Pace Gallery’s astonishingly vast new Chelsea headquarters alongside David Hockney, Fred Wilson, and works by Alexander Calder and photographer Peter Hujar. With Plumb Line, on view until October 19, she’ll mark her first major solo show in New York.

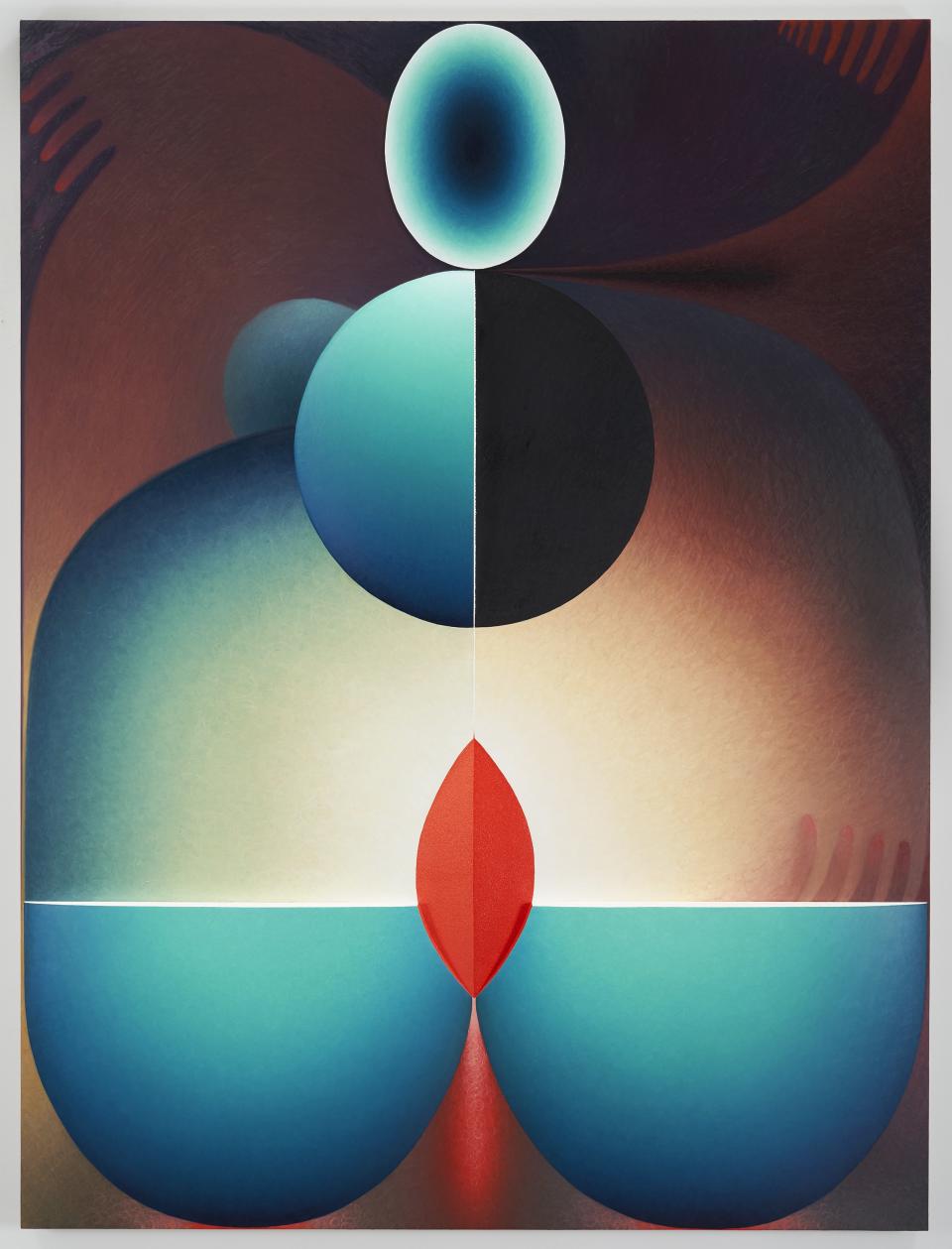

Pulsating with geometric forms in shades of orange, teal, eggplant, red, and green, Hollowell’s compositions announce themselves first as intriguing formal exercises—extended meditations on shape, symmetry, and juxtapositions of hue—only later revealing their shared preoccupation with the human body. “They’re really just my body in different positions,”says the artist. “I use the five elements: the head, the boob, the belly, the vagina, and the butt.” Get right up next to the canvases, which measure a stately (but not unwieldy) 72-by-54 inches each—big enough to fit a person inside—and Hollowell’s brushwork splinters into thousands of tiny curlicues. “I was working with the swirling texture as a blending mechanism,” she says. Now “I swirl everything, and let it be hair.”

The body has long been at the center of Hollowell’s artistic practice, including when she was an undergrad at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in the early 2000s. (Now based in Queens, she was raised on the West Coast.) “I went in as a sculptor, and I made sculptural, performative dresses that I would wear and have people, like, get under and dance around,” she recalls with some amusement. Years later, having segued into “super-didactic” figurative painting—and weathered the traumatic end of a relationship that resulted in an unwanted pregnancy—she began to pare things way down. “[My work] turned into this abstract, geometric painting language to talk about my own body. I took everything else out of it,” she says.

Birthing Dance, 2018

Made of a similar stuff, the pieces on display at Pace are heavily informed by the birth of Hollowell’s son nine months ago. “I started the studies for them in 2007,” she says, when she was just beginning to figure out how to break up her figure within a frame. “But I wasn’t thinking of them as pregnancy paintings. I added elements of the pregnancy later.” Among those elements were almost synesthetic applications of color: “It’s funny, in the ones that I made early on, while I was trying to get pregnant and in early pregnancy, I was using a lot of the yellow, and I feel like the green ones were all made toward the end,” she muses. “The red, I made in the second-to-third trimester, and I was huge. You just feel like death, it’s hot…so it had to be red.”

Bisected ovoids—isolated pregnant bellies—are stacked and fanned about the picture plane, radiating from a strong vertical axis and looking none too different from a diagram of the solar system. And this fits: To be pregnant, Hollowell says, is “otherworldly”—and “creepy as fuck.”

Her representation by Pace, which began in 2017, has also played a role. Since then, Hollowell’s practice has slowly scaled up; with the money from sales brokered by the gallery, she’s been able to work in a larger format, with better materials, and, most important, not entirely on her own. Once, the foam that she used for those slight protuberances came from the discards of a Fischli and Weiss show at the Guggenheim (where her husband, a sculptor, is an installer), and the sawdust was scooped up from woodworkers’ shops all over Bushwick. Now there are systems in place, and she works with a small team. “I’ve got someone who helps me with Rhino [a 3-D rendering program], the miller, my husband, and then a woman who helps me do the sculpting,” she says.

Standing in Blue, 2018

Aesthetically, Hollowell’s influences range from Georgia O’Keeffe and Agnes Pelton to Hilma af Klint, the Italian futurist Giacomo Balla, and the neo-tantric Kashmiri Indian artist G.R. Santosh. Asked how she discovered many of those people—Was it in college? Or while she was earning her M.F.A. at Virginia Commonwealth University?—Hollowell gives an appropriately millennial answer: Instagram. (At 36, she’s among the gallery’s youngest artists.) From Santosh and his transcendentalist cohort, she absorbed the illuminating effects of clear, strong tone against shadowy darkness—“Light [comes] in the form of total, pure, primary color; pure red or pure blue or pure yellow,” she explains—along with tantric motifs like the mandorla and the lingam. But Hollowell has divorced those things from their ancient Hindu underpinnings: In her art, the painted canvas is itself the end. “I’m trying to let the whitest area of the painting speak to some kind of transcendent mind space,” she says, gazing at the magisterial Standing in Blue (2018). Nevertheless, it’s “pure painting as a visually stimulating experience for the viewer,” she urges. “I’m not asking you to learn my religion; it’s all there. That’s it.”

For Pace senior director and curator Andria Hickey, there’s a pleasing continuity between Hollowell’s output and that of the other artists being shown this fall. With Calder, Hollowell shares a fascination with phenomenology and kineticism (over the course of the day, Hollowell points out, ambient light and shadow will play across her surfaces, subtly changing their colors and contours); with Hockney, a fruitful relationship to the digital world; and with Wilson, a willful (but abstracted) engagement with trauma. “It was not intended from the outset that you could walk through the building and experience such formal symmetry,” Hickey says. “But in thinking about how we wanted to tell the story of who the gallery is—what kind of artists we represent—those natural narratives formed.”

Loie Hollowell: Plumb Line, Pace Gallery, New York, NY, 2019

It’s to Hollowell’s credit that her work, personal as it is, has so many ways in. “She’s incredibly open, and she’s treading that perfect point between abstraction and figuration that allows for that openness,” Hickey says. From the viewer’s point of view, “once you’re okay with the fact that your own personal interpretation is good and welcome, other things about how you see the work open up, as well.” She hopes that when people come to the show, they’ll linger a while. “We want people to really spend time with the work,” she says. “It’s intellectual; it’s based in art history; but it’s also about your feelings. You can have a one-on-one experience in a space that’s already meditative, that already lets you go outside, take a break, come back, look again.” (Indeed, the 75,000-square-foot building, designed by Bonetti/Kozerski Architecture, boasts a sixth-floor terrace.)

For her part, Hollowell is just happy to have an audience. When I meet her at the gallery on installation day, she’s using tape to get hair and bits of lint off her paintings—anything to help people see.

Originally Appeared on Vogue