He lived through the Holocaust and died of COVID-19: His story of survival lives on

![Holocaust survivor Laszlo Fischer hugs his granddaughter, Mollie, during her 4-year old birthday party. Laszlo died from COVID-19 on April 5. [Contributed]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/cH5JQpgd_f_ed9TnQBP8hw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTEyNDI7aD0xNjU2/https://media.zenfs.com/en-us/usa_today_news_641/eaa93791fa810f8e0727fc7fbf6536a8)

WEST PALM BEACH, Fla. – Laszlo Fischer knew he was fortunate to live the 81 years that he did.

The Boynton Beach resident was just 6 years old in May 1944 when he, his brother, both sets of grandparents, his mother and an aunt were about to board a Budapest train headed for the Auschwitz concentration camp. A Hungarian soldier yelled “Fischer family,” pulling them out of line. They then spent the next several months at a Jewish ghetto in Budapest until the Russians liberated the city in February 1945.

Fischer was not as fortunate when it came to the coronavirus. He succumbed to the disease on April 5.

Palm Beach County recorded its first COVID-19 case March 12, the same day Fischer woke up with a fever and a cough.

Ten days later, he was admitted to Bethesda Hospital East with COVID-19 and pneumonia. Four days later, he was put on a ventilator.

![Laszlo Fischer enjoys a ride with his son’s family at Disney World in September. They were in Orlando to escape Hurricane Dorian. Laszlo died from COVID-19 on April 5. [Contributed]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/BS6O5vnV5ApMvcjJsJV9cw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0MQ--/https://media.zenfs.com/en-us/usa_today_news_641/8fc88ffe7b247eb8b58dbd8406e93516)

His time at Bethesda was like “a rollercoaster,” daughter-in-law Lauren Fischer said. “There were good days, bad days. Eventually, the virus attacked his kidneys, causing a shutdown of his organs. If he contracted the virus a month later, the outcome might have been different. There was so much back then that they did not know.”

She said her sister contracted the disease as well but was able to overcome it. Fischer’s family wanted the hospital to let her give Laszlo blood plasma to see if it would help but the hospital then did not approve of the procedure.

'Mama, I need you': She was on her deathbed after being run over by a car, but COVID-19 rules kept her family from visiting

Last goodbye: Saying goodbye to dying wife likely cost 90-year-old 'Romeo' his life, but he had no regrets, family says.

“There was an experimental drug we wanted to get him on. The hospital approved it but the pharmacy would not,” Lauren said.

Years ago, Fischer detailed his experience in Nazi-controlled Hungary for the University of Southern California-based Shoah Foundation. He is one of more than 3,000 Holocaust survivors to be interviewed. Researchers met with Fischer in Boca Raton on June 3, 1997. The Shoah Foundation provided a link to The Post to listen to the archived interview.

Fischer said no one knew the soldier who took them out of line that fateful day in May 1944. Even though he was only 6, he vividly remembers the soldier yelling out the family name. He surmises that the solider must have recognized someone in the family as they had operated a well-known bakery in the Buda section of Budapest.

“Standing in line, waiting to get on the train, was the scariest moment of my life. We were so lucky,” he said in the interview.

Life was very difficult for Fischer during the nine months he lived in the Budapest ghetto.

“I saw terrible things. There were as many as 10 people to a room in the apartment we were living in. There was very little food. We took water from the toilet to wash. I can remember how much I looked forward to taking a shower, which was not all that often.

“Then one day, we saw soldiers with different uniforms. It was the Russians.”

Fischer said it was difficult to describe what he went through. “I just don’t want it to be forgotten,” he noted.

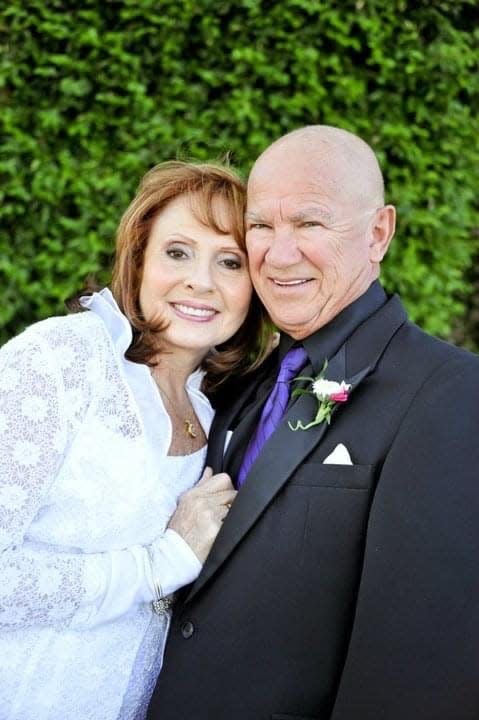

Even after the liberation, he said Hungary was not a good place to be if you were Jewish. Anti-Semitism was rampant. When the Hungarian revolution broke out in 1956, he emigrated to Denmark. He met his wife Vibeke there and they were married in 1965.

Laszlo said Denmark was very kind to Jews during World War II. He thought it would be a much better place to be. He was an outstanding soccer player and in 1967 in Amsterdam, he was part of Denmark’s national team in the Jewish Olympics or the Maccabiah Games.

“We had a wonderful life there,” he told the Shoah interviewer, “but we had a chance to go the United States in 1969 and we decided to go.”

He lived in the New York area and worked as an electrician for UPS for most of his adult life. He purchased a condominium west of Boynton Beach three years ago.

Vibeke called Laszlo her “Superman,” adding: “He was my life. He was my security. He was my love. He would wash the diapers on the stove in Denmark because they didn't have disposable diapers.”

![Laszlo Fischer and his wife, Vibeke, pose for a picture with two of their grandchildren, Mollie and Isaac. [Contributed]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/uMf2L1okFUBxJduNsknD2w--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTcyMA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en-us/usa_today_news_641/57e3cb12ba0599b448e3f6d46e13ff07)

His daughter, Monica, was born in Denmark in 1966. Ten years later, Michael was born in America.

Lauren and Michael married 11 years ago. “I looked at Laszlo as a father,” she said, “and I was like a daughter to him.”

Michael said his father was his best friend and was his best man at the wedding. “I hope that I’m half the man that he was.”

Monica called her father “a quiet and humble man, but always able to touch our hearts with his actions. We will forever treasure our special time with him.”

Vibeke was tested a number of times while Laszlo was hospitalized. She always tested negative but did test positive for the antibodies.

Lauren Fischer remembers one day asking Laszlo how he was doing at the hospital and whether he needed anything. “He wanted so much to take a shower,” she said, noting she couldn’t help but think back to his days in the Jewish ghetto in Budapest when he told the Shoah interviewer how much he looked forward to taking a shower.

Shortly before he passed away, the family was able to arrange a five-way telephone call with Laszlo and a Rabbi who said a prayer. It was all very touching, Lauren said.

![Laszlo Fischer poses for a picture with his extended family in New York City last Thanksgiving. [Contributed]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/VVjm2NigvRIJBkjo9TJoRQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTcyMA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en-us/usa_today_news_641/363a7abf7aed5a8d8e2ab34142e780f6)

Lauren, who writes children books, dedicated a poem to Laszlo a month after he passed. Part of it reads:

“One month ago you became an angel. Words cannot express how empty we feel. We just want one more hug. One more laugh. … One more day. We could not hold your hand when you needed it. Saying goodbye is never easy. But not being able to say goodbye is extremely hard.

“And we will talk about you to our children every day. Watch over us and send us messages that you are OK. You will always be our Superman.”

Fischer is survived by his wife, Vibeke; his daughter, Monica and son-in-law, Jay; his son Michael and daughter-in-law, Lauren and five grandchildren, Sophie, Hailey, Jessie, Isaac and Mollie.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Holocaust survivor, 81, dies from coronavirus in Boynton Beach