Little Richard Made Male Vanity Look Like the Coolest Thing in the World

“I’ve been in this business for 20 years,” Little Richard said on The Dick Cavett Show in February of 1970, “and I am the best-looking man in this business, without any doubt. I’m very, very beautiful. And I’m not conceited. I’ve never been conceited—I’m convinced...that I’m the best-looking thing.”

Little Richard, who died this past weekend of bone cancer at 87, was used to insisting on his beauty—it was arguably as important to his set lists as his foundational hits like “Lucille” and “Long Tall Sally.” The show’s audience laughed, delighted by his braggadocio—although you can absolutely tell he’s absolutely serious, in a green suit the color of a fresh tropical sprout, the top cut in a wide V-neck to show off his clavicles, and the pants cropped a bit to show off his little Cuban-heeled boots. In his usual face—pancake makeup, the pencil mustache, hair in that long tall pompadour, with a proud line of eyeliner beneath his bottom lashes—he really did look like the best-looking thing in this business, with his high, gorgeous cheekbones, his eyelashes fluttering like an ingenue’s, and his mouth in a frisky moue. He asked Cavett if he could say something, to which Cavett replied, “Well, you just did, but go on.”

He flung his arms open, and the fringe on his sleeves went wild. “LET IT ALL HANG OUT!” He pawed his wrist in the air, knowing full well the homophobia that might spark in the folks at home. “LET THE BEAUTIFUL LITTLE RICHARD, FROM DOWN IN MACON, GEORGIA! I AM THE BRONZE LIBERACE. SHUT UP!” The audience burst into laughter and applause. “My my,” he said, a preacher recovering after speaking in tongues. “My my.”

Of course, it would be more accurate to say that Liberace was the white Little Richard. By the time he appeared on Cavett, Little Richard’s imitators—namely Mick Jagger and Jimi Hendrix—were doing something a little less studied, and his regime of commanding flamboyance, less obvious in its camp than Liberace’s, was as arresting as it was when “Tutti Frutti” came out in 1955. Little Richard would spend much of his career convincing the establishment and the gatekeepers that he not only belonged in the pantheon, but had in fact laid its cornerstone—that he pioneered the all-consuming male vanity of rock stardom, that he created its unique language by merging shocking sounds with far-out personal style, and that it was criminal that white musicians like Elvis made more money than he did...by recording his songs. He performed a similar monologue in 1990 on The Arsenio Hall Show, with a few updates—the camp is in full session: “I give them two snaps and a broken wrist!”—and other lines chillingly unchanged. But when he landed that line, “I’m not conceited—I’m convinced,” everyone got it, howling in laughter. By then, everyone knew his language.

Little Richard

Getty ImagesGender-fluid fashion, men’s makeup, and personal style are basically mainstream in fashion now. But getting to that place required pioneers to shock audiences by doing and wearing the truly weird. Little Richard held both the value of personal expression and the alienation of being bizarre in the highest regard: He was a great beauty, and a real freak. He had beautiful cheekbones, the kind that launch a lifelong modeling career, and bedroom eyes that he electrified into something maniacally provocative—“Ooh, you like that!” From the beginning, when his colorful suits fit lean and a little baggy, and he’d throw his leg up on his piano while pounding the keys, style was part of what he did, in this art form that launched not simply on radio but also on late-night television. It wasn’t just that he was an original that propelled him forward—he embraced the discomfort of confusing and seducing an audience. Rock ’n’ roll is a story of borrowing (and flat-out theft), of course, and Little Richard himself was a borrower—he borrowed his pompadour and ritzy playing style from the openly gay R&B performer Esquerita. Like many camp icons, Esquerita worked in a secret language, almost designed to be underground. (Indeed, he didn’t even record solo until after Little Richard, who allegedly first saw Esquerita getting off a bus in Macon, had released several of his hits.) But Little Richard wanted his inner freak on display at billboard, rock ’n’ roll icon scale.

PEGGY FLEMING;LITTLE RICHARD;DICK CAVETT

Getty ImagesLittle Richard is the emblem of a time when rock ’n’ roll was dangerous. He was too sophisticated to be a mere provocateur, and his lifelong swerves between proudly proclaiming his sexual identity and renouncing queerness on religious television don’t seem designed to shock so much as to answer some more internal demon. But he fine-tuned and evolved a style that has remained so profound—splashy, elegant, strange, glitzy—it looks revolutionary every time it emerges: the way Elvis wore his suits oversize, and his later dedication to the sequined works of Nudie Cohn. The headband-and-poncho combination of Hendrix; Liberace’s camp; Mick Jagger’s glitter and pout. The quizzical seduction of Bowie. And, of course, the sensual, sexual urgency of Prince. Over the past five years, fashion designers have picked up all these threads to create a newly liberated but manicured vision of menswear, with designers at Gucci and Saint Laurent and muses like A$AP Rocky and Harry Styles. They are all reading from and building on a script that Little Richard wrote.

If Little Richard didn’t invent it, someone else would have. But with clothing, especially menswear, you need that one revolutionary figure to show it’s not only okay to wear something, but to insist on it. Nearly a year after that first Cavett appearance, Little Richard went on again, this time with a bizarre lineup: actress Rita Moreno; Erich Segal, a Yale professor and author of the treacly Love Story; and the literary critic John Simon. Segal and Simon engaged in a debate as old as human language—whether Love Story should be dismissed because it is popular but loathed by critics—arguing in fine-tuned elocution for 15 minutes until Little Richard burst in: “RIGHT ON!” he said to Segal. “Let me say something,” he said. “Y’all been talking all night,” and added that he could clear all this right up.

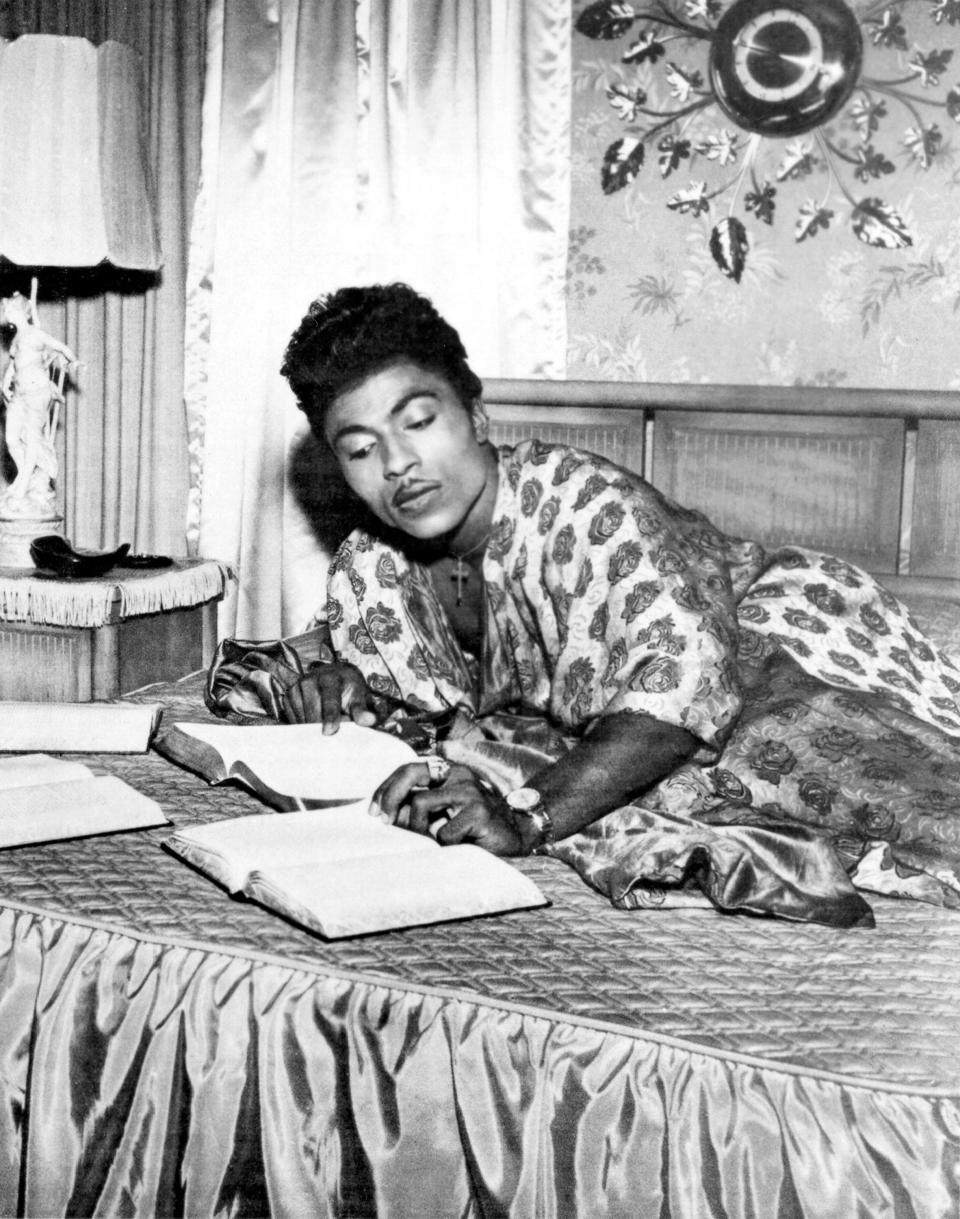

Little Richard Studies The Bible

Getty Images“If I was in a play,” he said to Simon, “I wouldn’t care what you write. It wouldn’t make no difference, ’cause I wouldn’t think you would know anyway.” He went on, “I don’t think that a person can tell how the beans supposed to be in the pot when they don’t even eat beans. You understand that?”

He leapt to his feet. “You see how I dress?” He was wearing gold brocade bell bottoms with a matching tunic whose sleeves unfurled regally into a cape, with a headband and caramel boots. “I do what I feel. I don’t care what critics say—‘He’s awful, he don’t matter’—because most of them, their writing [is] terrible. They’re old and outdated. That’s the truth! They don’t know what’s going on. Never been on, can’t get in, can’t get out.” He ended with his unofficial rejoinder to everyone who’s ever questioned the importance of being truly weird: “SHUT UP!”

Originally Appeared on GQ