Little Oblivions Is the Perfect Vehicle for Julien Baker's Explorations of Faith

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On the second track of Julien Baker’s third album, Little Oblivions, a car engine catches fire and doubt filters in through the smoke. “It's not like what I thought it'd be,” she sings to God about her relationship with her faith, “the gruesome beauty of your face in everyone I meet.”

Victor Hugo wrote that “to love another person is to see the face of God,” but on "Heatwave," the Tennessee singer-songwriter asks what exactly it is she’s seeing when she witnesses the suffering of strangers. Is it “all part of the deal” of following God? Baker wrote the song thinking that a Christian willingness to accept suffering as inevitable “is a huge obstacle to [her] faith and [her] understanding, this insanity and unexplainable hurt that we’re trying to heal with ideology instead of action."

Baker’s latest album feels like the third and final act of her bildungsroman, after 2015’s Sprained Ankle and 2017’s Turn Out the Lights. It’s a work that quietly examines the collapse of faith and trust on a personal and institutional level. It builds to an understanding that we can make our own systems of belief and reason outside the power structure of organized religion—and that we may be better off for it.

She also fuels this insight with a new sound. An organ blast on “Hardline” opens the record with a warning signal that she’s ripping up the rule book of what her music is supposed to sound like. From deceptively light moments of pop rock (“Relative Fiction”) and songs that collapse in a flurry of guitars (“Hardline”), Little Oblivions is gutting music written with a poet’s delicacy, flair, and scalpel, scored by a hardcore veteran who understands thrashing’s cathartic potential.

At 25 years old, Baker writes with remarkable consistency—to the point where people can list all of the things she makes songs about like categories on Jeopardy: religion, addiction, depression, death, redemption, evil. Although her subjects remain similar, what she learns in asking life’s big questions at 17, 19, and 23 is always evolving.

The first time I saw Baker, touring with her sparse debut album, Sprained Ankle, I could feel the audience hold their collective breath when she reached a certain point in the song “Rejoice.” “I think there's a God and He hears either way,” she belted, disrupting the song’s sedate atmosphere. Watching her painstakingly excavate the sort of dark parts of herself that we all have and like to pretend don’t exist, the muscles in her neck straining as she put her faith in God and herself to task at full volume, for a moment, it wasn’t too hard to begin to believe again.

My faith, at the time, had been in doubt. At the same age that Baker was writing “Rejoice,” I was reading Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. In the first chapter, “Heaven and Earth in Jest,” essayist Annie Dillard witnesses a giant water bug eat a frog from the inside out while on a walk. “I watched the taut, glistening skin on his shoulders ruck, and rumple, and fall,” she describes. “Soon, part of his skin, formless as a prickled balloon, lay in floating folds like bright scum on top of the water: it was a monstrous and terrifying thing.”

Her moment of private, childish joy, traipsing down the creek, is interrupted with the banal evil of the animal kingdom, as it will be many times throughout the book. Seven years after reading it, the image of that frog—its body paralyzed, “reduced to a juice,” and sucked out in a single bite—still haunts me, and it prompts Dillard to ask, “If the giant water bug was not made in jest, was it then made in earnest?”

That paradox—Why would a benevolent God create evil and permit suffering?—the question of theodicy, triggered my own crisis of faith. On Little Oblivions, Baker is at her most self-destructive when she assumes that her bad behavior, like the suffering she witnesses on “Heatwave,” is inevitable. She sings, “Start asking for forgiveness in advance / For all the future things I will destroy,” on “Hardline,” and “I've got no business praying / I'm finished being good” on “Relative Fiction.” Crucially, though, she sees the path to her own freedom when she finishes the latter’s couplet with the lyric, “Now I can finally be okay / And not the way I thought I should.”

It’s a startling evolution, even from her most recent work in 2018 with her Boygenius collaborators Phoebe Bridgers and Lucy Dacus on the song “Stay Down.”

So would you teach me I'm the villain, aren't I?

Aren't I, aren't I the one?

Constantly repenting for a difficult mind?

Push me down into the water like a sinner

Hold me under and I'll never come up again

As a once-Catholic, the Protestant emphasis on original sin baffles me. Baptism does the trick for the former, but the idea that we are simply born evil and that the sin was absolved only through the ultimate suffering and death of the son of God seems like more of a burden for the latter. A singular ritual cleansing isn’t enough for Baker; as she sings on “Stay Down,” she might as well stay submerged.

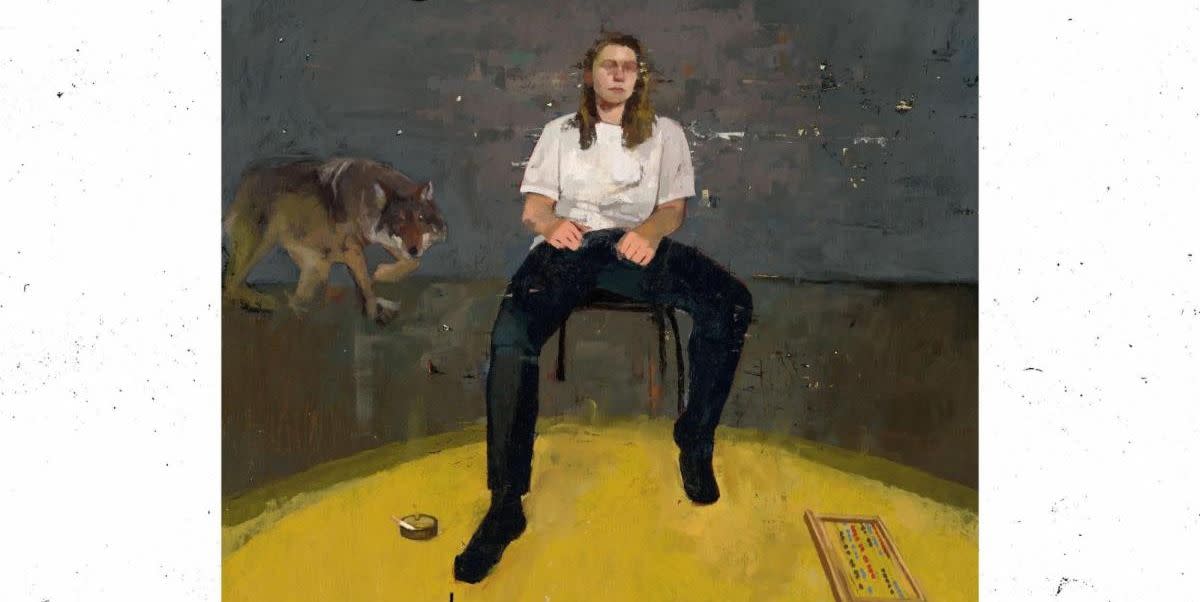

“I find myself, often, wishing for punishment because that would make sense in my brain. That would even out the abacus of right and wrongdoing, and that would make everything feel okay,” she told Uproxx. She reiterates feeling undeserving of forgiveness and being saved on the album closer, “Ziptie,” when see sings, “Oh, good God / When you gonna call it off / Climb down off of the cross / And change your mind?”

“Cruelty is a mystery, and the waste of pain,” Dillard ultimately concludes in “Heaven and Earth in Jest.” The question of theodicy is unanswerable; we create our own suffering if we let it consume us, so Dillard finds the silver lining elsewhere. “The answer must be, I think, that beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.” I think Julien Baker would agree.

“I don’t doubt God,” she told the New Statesman in February. “I am, in fact, certain that there’s something out there, even if it’s just God manifested in the dignity of other human beings.”

If God isn’t there, or simply doesn't care, we still have a responsibility to care for ourselves and others, and search for our own moments of divinity in the lives we do have. If there is a way for us to be saved, it is through our loved ones in the way Baker sings about on “Favor.” Dacus, who sings backup on the song with Bridgers, says the song “makes [her] think about how truth only ever breaks what should be broken, and how love is never one of those things.”

I think the same impulses that drive addiction, power, and control can steer a person’s journey with faith, and that there's a hair's breadth between oblivion and enlightenment. If we get to choose, and I think we do, then maybe to seek little oblivions is to search for God in everything.

You Might Also Like