Lisa Taddeo Is Saying The Quiet Parts Out Loud

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Lisa Taddeo’s work is addictive. Once you start reading, you (legally) cannot stop. You’ll find yourself flipping through the crisp pages of her books late into the night, devouring the inner psyches of her haunting, irresistible female leads—both fictitious, like in Animal, and adapted from journalistic pursuits, like the New York Times bestseller Three Women.

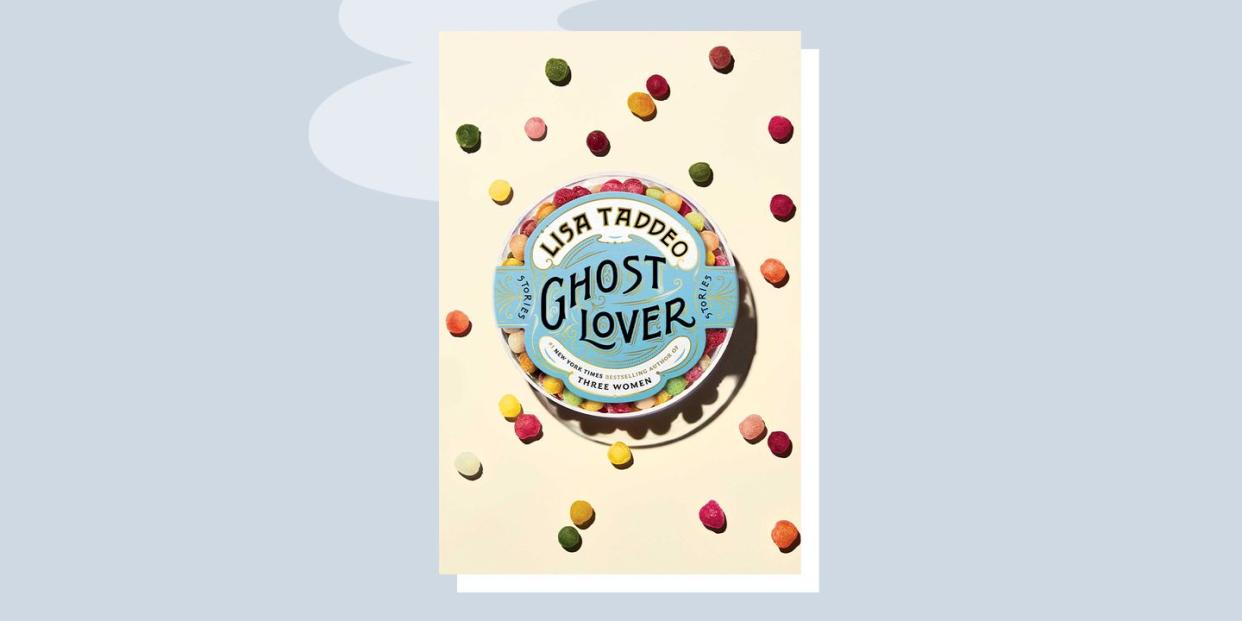

Taddeo’s prose speaks to the seedy core of us, capturing the experience of being a woman in a world that hates women, but simultaneously loves to fuck them, both literally and in the abstract. And for fans hungry for more from the author, there’s news: a collection of Taddeo’s selected short stories, Ghost Lover, has just landed. The anthology includes previously published works like the dark, sexually charged friendship romp “Suburban Weekend,” as well as a meditation on aging and women’s social capital, “Forty Two.” You’ll also find exciting new stories like the titular work, “Ghost Lover,” which employs a striking second-person framework to narrate the thoughts of a woman who creates a dating app where hot girls craft indifferent messages to men on your behalf.

Ultimately, if you’re won over by gorgeous sentences and fiction so true to your experience it feels real, there’s something for you in Taddeo’s work—particularly this collection examining a breadth of characters, all connected by Taddeo’s talent for capturing the heterosexual female psyche at its best and its grueling, unspeakable worst. Speaking by Zoom after a morning on set (the rights of both Animal and Three Women were acquired by MGM for adaptation), Taddeo spoke with Esquire to discuss Ghost Lover in depth. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Esquire: A theme of this collection is women trying to control their own bodies by manipulating them through starvation, over-exercise, dieting, and the like. Your characters’ desire for thinness seems to be tied to attracting men. Is writing about the lengths women go to in order to manipulate their bodies intentional for you? Or rather, as a woman yourself, is writing about this catharsis?

Lisa Taddeo: It's a bit of both. We're living under this patriarchal hangover right now. Something I said in Three Women is that heterosexual women look at each other the way that a man does. A lot of our gaze is still the male gaze. I came of age in the 80s when there wasn't social media. There was no Instagram. But all the books and stories that we read told us that beauty was a commodity. One of the reasons I write a lot about looks and the way that women feel about the way they look is because it's what we all talk about.

Someone just asked me what advice I would give to young women, and I have tons of advice. But I also said that I would like to ask them for advice, because I think that younger generations are so much more self-aware of where their value lies. There's a lot of ageism in Ghost Lover, and there's a lot of material about the way that we look. I think we have been raised to believe beauty is one of our largest commodities, and when we go out into the world, it is reinforced in so many ways. It's so infuriating to me that there's no control of it. The only way that I can control it is to write about it. My generation and beyond, there's a cattiness there. I think the younger generations don’t do it as much. It's self-sabotage, and we use our own strengths against each other.

ESQ: It’s interesting to hear you say that the younger generation doesn't pick each other’s physical appearance and sex appeal apart. It’s a faux pas to do so, but it's still done. Maybe you're not going to voice it, but I feel really seen in these pages, because I'm like, "Oh thank God, I'm not like a bitch for thinking this way."

LT: I'm so grateful to hear you say that, because I think we can feel like bitches. Whenever I'm like, “Oh my god, I look terrible, and then there's 75 other women going, 'No, you're beautiful!'” It's like okay, thank you. But there's something to be said for allowing someone to say out loud, “I am feeling unattractive.” It doesn't make you a non-feminist. I think it makes you a non-feminist to excoriate another woman for having a feeling that she wants to communicate.

ESQ: I think Ghost Lover is a deeply feminist work. It would be a misreading to think that you're promoting negative thought processes or actions. You're shedding light, which is important.

LT: I knew there was a potential for misreading. I think that the same thing is true of whenever there's violence toward women on television or in movies. There's this whole, “Oh, we can't show that” instinct. If we don't show it, we're not making it not happen. We're just quieting that thing and making people who it has happened to feel like they're the only ones. That's how I look at everything I write.

ESQ: You capture the essence of U.S. cities like New York, Los Angeles, and many other parts of the world so beautifully. How do you decide where a story’s setting will be? What does setting mean to you, seeing as you’ve traveled so much?

LT: Setting is so wildly important to me. Whenever I think of love stories that I've had, or obsessions I've had, the place has been so important. It just sticks with you, like the first bar where you meet the guy that you get obsessed with. Whenever and whatever the place is, it lives in you. Now that I'm married, when I visit new places, I’m not having any of those new love experiences. I'm just having fights or calm emotional safety with my husband and kid.

When I was in LA, it was very difficult for me, and also so beautiful and unknowable and mysterious. I wanted to know more about it. I say to my husband every time we go to New York, “New York is over.” He hates when I say that, because all he wants to do is go back there. For me, I feel like I excavated New York for myself. I went to every bar, I went to every restaurant, I looked for love around every single street corner. It holds so much of those feelings and emotions for me. New York is always going to be the big one.

When I say New York is over, I don't actually mean it. I’m just trying to get my husband to not want to move back there. It's weird because New York is both the epicenter of the universe and also not. Having traveled so much, I feel like no matter where you are, you're still coming back to yourself. Moving around to different places gives you different experiences. I think that if I'd stayed in New York the whole time, I wouldn't have gotten out of my career what I got out of it.

I was constantly like, “Should I leave? Should I stay?” And every time someone left, it was like “Why would you leave New York?” It’s crazy, because you can do whatever you want. I mean, obviously I don't know what your restrictions are, familial and otherwise, but one can technically do what they want. And that is a scary, scary notion.

ESQ: The juxtaposition of women at the beginning of adulthood versus those enmeshed in adulthood is so clear in your writing. Many of your stories follow women who are hyper aware of their youth and attractiveness, as well as those who are mourning the loss of youth. What makes you write about the perceived competition between younger and older women?

LT: I grew up with a mom whose main commodity was her beauty. She was the most beautiful in her family and the most beautiful woman in her town. Her beauty was the incredibly objective kind, very much like Sophia Loren. Men always looked at her on the street. A cornerstone would be watching my mom, watching other people watch her, and going “Wow, that's what beauty does.” When she started getting older, she would talk about losing her looks and feeling very upset about that. She would call herself vain and say, “I hate that I feel this way.” Her growing insecurities as she got older made me very sad.

For me, I've never felt that way about myself. If I lose my ability to write, that's my commodity, that's what I feel that I'm good at. If I lost that, or if age was taking that away from me, it would make me feel awful. My mother's commodity was her looks. I don’t think we should judge. This is mine, that’s hers.

When I was 24 or 25, I went to the Kentucky Derby to cover it for a story. I remember walking by a couple eating steak. I just took the man’s fork and put it into a piece of steak, then put it in my mouth. Then I put the fork down and I kept walking. Not drunk, just testing what I could do. I'm now on the flip side of that. There was a young waitress the other night with me and my husband, and she was being flirtatious. I was just like, “Oh my God. I was there. Now I'm here.” And that's the thing I'm interested in in my writing. We are all going to be there.

When we’re young, we act like we're never going to get old, and when we're old, we act like we were never young. That, to me, is the big misfortune. We are removing the potential and the great hope of having intergenerational friendships with each other by doing that. There's nothing more exciting to me than having younger friends or older friends.

ESQ: Two of these stories focus on dating apps and how people rely on them to weed out the messiness of dating, as well as the pitfalls in the very premise of many dating apps. What do dating apps say about our patience for modern dating?

LT: After my parents died, I was very sad. I didn't want to go out. I wanted to find someone, but I wanted to do it while I was inside my house, so I was on Match.com. I wanted to find someone who was going to love me and care for me because I was this wounded dying animal.

I didn't really find anything too exciting, but I remember the excitement of going, “Oh, maybe on page 27 is where I’ll find the guy that's going to be perfect.” There was just something about clicking into the wee hours of the evening and feeling like I could look, instead of being looked at. Post-marriage, I went on to Bumble because my brother had recently separated from his wife and was in a really bad place. I made a profile for him and I responded to the women that wrote to him. I was batting 1000. I was like, “Oh my god. I'm married to a man, but someone should have told me I could get any woman.” It would just be me and this woman talking about Elena Ferrante.

ESQ: Close female friendships are so essential to our survival, though they are also some of the more grueling connections in our lives. You capture them so well: all the points of contention, the hurt feelings that go unaddressed, the passive aggression, the resentment. What makes you want to write about these dynamics?

LT: We are currently still best friends, but I had a very close female friendship that, when I met my husband, exploded because of hurt feelings. We were single together and we were also so attached to one another. We were always going out to meet people and also hanging out with each other, fully excited to be in one another's company.

When that friendship took a timeout, it was really awful for both of us and left a mark on me. I think what that experience taught me is to be super honest going into a friendship with a woman. We do the same things with non-platonic love. We show our best selves, right? So what I do now with female friends is I tell them upfront, “Hey, here's my list. It's my top ten list of faults and things that I will do. I will have panic attacks and I will not be able to go out one night because I'm thinking that I'm going to die.”

With a friendship with a woman, if they find out something about you that they don't feel like they knew the whole time, it's almost more of a betrayal. I think female friendship is so beautiful and haunted at the same time. I could just think and write about it forever.

ESQ: You’ve said that you prefer the short story structure to novels. What do you love about the short story format, and what are your hopes for this collection?

LT: I have always loved short stories since I was a kid. I don’t know why more people don’t read them. What I love about the form is that you have the ability to create a world very quickly. A really good sentence is so important to me. All of the people I admire write the most beautiful sentences. In a short story, you have more time to do that. In a novel there's less space. There needs to be more space for plot. In a short story, it's compact, and you can say more.

I think about my daughter, and I think about what it's going to look like out there. I don't know if she's going to be gay or straight or what, but for me, it's like “Here's a primer. Here is what I've been through and seen, so that if you see some of these things, you won't go, ‘Oh fuck.’ You might go ‘Oh, okay. I've heard about this before. Thanks, mom.’”

You Might Also Like