Life after Sandy: How New York is preparing for the next superstorm

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy reminded the nation’s most populous urban area that it wasn’t immune to the whims of nature. The storm left more than 100 people dead, destroyed entire communities, crippled infrastructure and caused billions of dollars in damage. It underscored the importance of fortifying the tristate area’s coastal communities against storms and sea-level rise in a way that no amount of climate research could ever do.

Over five years later, the region is still dealing with some of the effects. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority plans to shut down the popular L train, a vital connection between Manhattan and Brooklyn, for 15 months of repairs starting in April 2019. During Sandy, the century-old Canarsie Tunnel under the East River was flooded with 7 million gallons of salt water, causing lasting damage.

Jimmy, a retired construction worker, lost his rented home of four years on the East Shore of Staten Island in Sandy. His landlord took a government buyout and a friend took Jimmy in. “There is no home. I’m staying with somebody,” he told Yahoo News. “It’s good and bad. More bad than good. It’s the way it is. You know?”

Photos: Hurricane Sandy on Staten Island: Then and now »

When asked if the city has prepared well for another superstorm, he responded, “I believe that they have, but there’s a lot more to do. You know? Just in case another one hits us like that.”

The 2018 Atlantic hurricane season, which officially begins on June 1 and ends on Nov. 30, is expected to be more turbulent than usual — with estimates for the number of tropical storms ranging from 14 to 18. The average for named storms from 1950 to 2017 is 11, according to researchers.

New York and New Jersey have made significant changes to protect against the next superstorm, but no two storms are the same. Planners have to think in terms of centuries, and to consider long-tail threats such as earthquakes and tsunamis as well as hurricanes and the Atlantic coast’s notorious nor’easters. Some planners worry that in preparing for another catastrophe that may be 100 years off, the region is overlooking the risk of smaller, more frequent storms and tidal flooding from rising sea levels.

Yahoo News contacted the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the New Jersey Office of Emergency Management (NJOEM), the New York City Office of Emergency Management (NYCEM), the Mayor’s Office of Recovery & Resiliency (ORR), the New York State Division of Homeland Security & Emergency Services (NYS DHSES) and various experts on storm surge and sea-level rise to find out what’s been done and what still needs to happen. But the most important question can only be answered by the next superstorm: After all that work, just how vulnerable is the region to another catastrophe?

Part I: Building back stronger, higher

The most important task after Sandy was rebuilding what had been lost but with sturdier foundations, higher elevations and stronger protections.

Megan Pribram, assistant commissioner for planning and preparedness at NYCEM, told Yahoo News, “After any emergency, we do an after-action review and look at what went well and where we can make improvements. And we learned a lot from Hurricane Sandy.”

Jainey Bavishi, the director of New York’s ORR, said that although no two storms are the same, “New York is certainly safer since Hurricane Sandy.” She said the city strengthened its coastal protection, streamlined access to critical services in the event of an emergency, upgraded city-owned buildings to withstand extreme impacts and invested in stronger emergency plans at the local level.

“We’re making sure neighborhoods are safer and can thrive in the event of a disaster,” Bavishi told Yahoo News. “We have work to do. We have coastal protection projects underway on the east side of Manhattan, Red Hook [Brooklyn] and on the East Shore of Staten Island.”

Laura Connolly, a public information officer for the New Jersey State Police Emergency Management Section, said they’ve made many changes to keep New Jersey safe, such as raising homes off the ground, buying property in flood-prone areas and installing better drainage for roads. The Long Branch boardwalk, which was destroyed during Sandy, has been rebuilt with sheet-piling for its entire length to protect against waves.

“Public assistance traditionally brings a structure back to the way it was. But what we’ve tried to do is enhance it so we don’t have the same problem over and over and over again,” Connolly said.

In the storm’s aftermath, New Jersey established a huge initiative with $1.34 billion in federal funds that allowed home owners to repair or rebuild their properties.

“We’ve really been able to increase elevation in the flood-prone areas,” Connolly said.

Some high-risk areas have opted for green infrastructure, which reintroduces natural elements to manage storm water where possible. This involves planting trees and restoring wetlands and floodplains — instead of building more water-treatment plants and increasing the height of levees. Though not a cure-all, rain gardens and permeable pavements, unlike concrete or blacktop, can absorb excess water and control runoff.

The NYS DHSES has managed more than 4,700 projects under the FEMA Public Assistance program totaling in $13.8 billion and more than $1.4 billion in hazard mitigation.

Part II: Changing priorities

According to the FEMA Region II, which covers New Jersey and New York, Sandy fundamentally changed the attitudes of all levels of government workers in favor of resilience.

In January 2013, then President Obama signed the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act and the accompanying Disaster Relief Appropriations Act into law. This legislation expanded FEMA’s power and approved $60 billion for disaster relief agencies.

Recovery programs were begun in the offices of New Jersey’s governor, New York State’s governor, New York City’s mayor and at the federal level.

Ken Rathje, the federal disaster recovery coordinator for FEMA Region II, which is also helping Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands rebuild after Hurricanes Irma and Maria, said regional administrators and technical review teams regularly meet to discuss projects in and around New York City.

“I personally think New York and New Jersey are much more prepared for the next disaster,” Rathje said. “We have a lot of activity going still for Sandy recovery.”

FEMA’s National Disaster Recovery Framework guides states and local jurisdictions on procuring recovery support after a disaster — as well as pre-disaster recovery planning.

Part III: Efficiency

The Stafford Act of 1988 created a system for FEMA to deliver financial assistance and disaster relief in the aftermath of a natural disaster, but it wasn’t perfect. The Presidential Policy Directive 8 of 2011 improved it by making it easier for FEMA to transfer money where it is needed.

Andrew Martin, acting chief of FEMA Region II’s Risk Analysis Branch, said they’ve taken steps to make sure that this money is properly allocated. For instance, their group dedicated to protecting the region’s infrastructure has been subdivided into various sectors — such as power, waste water and transportation.

“That will allow us an extraordinary amount of efficiency in terms of how we fund the recovery and also how the recovery is managed. It will bring everything under one roof for each of those sectors, and make sure we’re injecting mitigation activities into each and every project where we can and where it makes sense,” Martin told Yahoo News.

Shelters have been stockpiled with many things that were in high demand immediately after Sandy, Pribram said. This includes clothing, baby cribs, durable medical equipment and administrative supplies.

In addition to long-term capital projects, NYCEM and ORR are working together on interim flood-control measures, such as deploying large sandbags ahead of storms.

“It’s really about fortifying some of that critical infrastructure,” Pribram said. “We’re a lot more prepared than we were. Every time we learn something from this. So, a lot of those things I talked about put us in a better position.”

Part IV: Refining evacuation zones

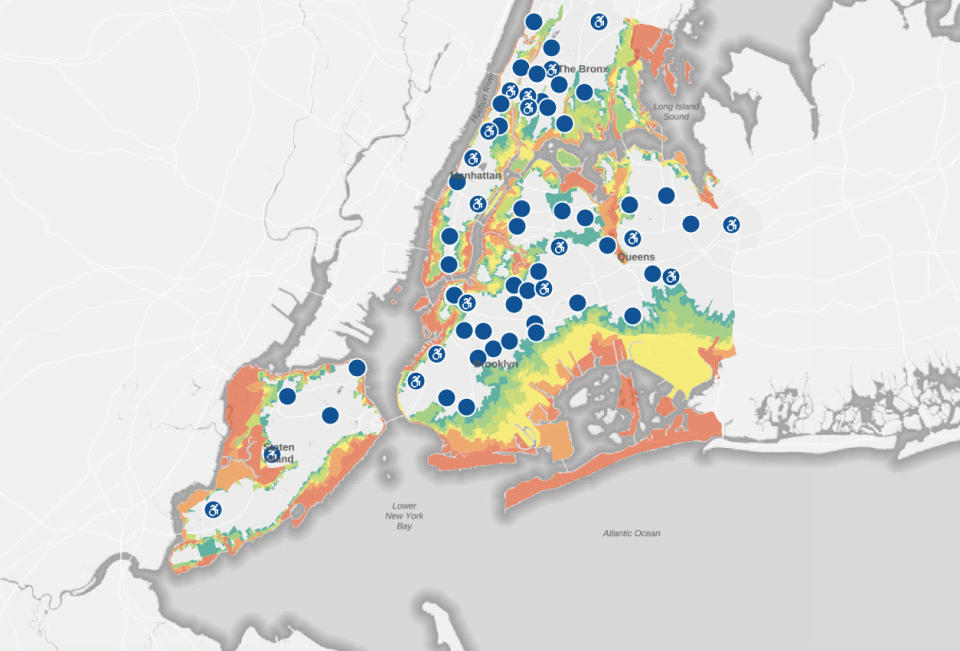

A major change after Hurricane Sandy was the introduction of hurricane evacuation zones. Pribram, of the NYCEM, explained that there used to be three evacuation zones (A, B and C), but NYCEM worked with the National Hurricane Center to increase that to six (now designated 1 through 6), a move to give the city more flexibility, improve its decision making and avoid over- or under-evacuation.

The overall evacuation area has been expanded as well. Almost 2.4 million New Yorkers lived in the previous zones but about 3 million live in the new ones. NYCEM uses the Sea, Lake, and Overland Surges from Hurricanes (SLOSH) model to outline thousands of storm scenarios for the region with a variety of variables, such as wind categories and community characteristics, to determine which areas are at highest risk of flooding.

Zone 1, which covers low-lying shorefront communities such as the Rockaways, has the greatest risk of flooding. Zone 6, which includes parts of Harlem and the South Bronx slightly further inland, is expected to be safe from all but the strongest storms.

“This allows us to evacuate for different types of scenarios and not over-evacuate. Soon after that, we tried to get information out about those zones. We have increased outreach in those communities to make sure people are aware of what zone they are in,” Pribram said.

New York launched the “Know Your Zone” and “Ready New York” campaigns to help residents figure out the risk factor of their zone and how they can make an emergency plan if necessary: gathering supplies, preparing a “Go Bag” and choosing a meeting place.

Part V: The civilian’s responsibility

The obligation to repair what has been damaged and protect against future storms also falls on businesses and homeowners.

Robert Freudenberg is the vice president for energy and environment at the Regional Plan Association, a nonprofit that creates long-term plans for health, sustainability and prosperity in the tri-state area.

Freudenberg said people with seaside property can expect a lot of troubled times ahead, and it may be time for them to reevaluate how long they want to stay in their homes or neighborhoods because “we can’t wall off the entire coastline against these challenges.”

“It sounds gloomy. We don’t know exactly when things will strike but we’re at a point where storms are more intense and the sea levels are rising. It’s not just going to be the storm. At some point, when the sea-level rise reaches a certain point, it’s going to be every high tide that causes damage to neighborhood,” he said.

Financial services companies like Moody’s have already started reevaluating properties along the waterfront and whether they are worth the investment.

Freudenberg is also concerned about the financial impact future storms will have for people with low incomes, who cannot afford to protect their own homes as wealthier homeowners might, through elevations and sturdier foundations. This variable could exacerbate the already stark societal challenge of income inequality.

The NYS DHSES’ Citizen Preparedness Program has trained nearly 275,000 with resiliency skills — preparing for, responding to and recovering from disasters — since it was launched by New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo in 2014.

Part VI: Addressing various hazards at once

Patrick Tuohy, a federal disaster recovery officer for FEMA Region II, said they assess the risks and estimate the likely needs for any given area as a disaster approaches. Nevertheless, it’s impossible to prepare for every contingency, which is why it’s important to embrace an all-hazards approach.

“Typically, some of the preparation and even in the building efforts that you do for a hurricane have benefits across earthquake risks, tsunamis so you’re taking a comprehensive approach to risk reduction rather than a siloed approach to one risk,” Tuohy said.

With Sandy such a recent memory, most public attention is focused on the risks of another superstorm, but the city faces other climate threats as well.

The New York City Panel on Climate Change projects that by the 2050s New York City will see a 4.1- to 5.7-degree Fahrenheit increase in average temperatures, a 4 percent to 11 percent increase in annual average precipitation and a one-to-two-foot sea-level rise.

Sea-level rise is not the same across the globe. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that sea-level rise worldwide will be five to 32 centimeters by 2050.

Hurricane Sandy caused the worst flood in New York City’s nearly 400-year history. It was four feet higher than any flood in the past hundred years and several feet higher than anything in previous centuries.

Philip Orton, a research assistant professor at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J., researches storm surges, climate change and ocean physics. After Sandy, he said, authorities started to make ambitious plans to prepare for another storm of that magnitude. His research indicates that Sandy was a once-in-300-year flood, and that vulnerable areas around New York (such as the Meadowlands, eastern Staten Island, Red Hook and the Rockaways) need more immediate changes to prepare for smaller but still consequential 30- and 50-year storms.

“The ultimate thing would’ve been if [former New York Mayor Mike] Bloomberg instead of having this one megaplan had a protection-against-common-floods plan and a protection-against-big-floods plan. But I think the sense was that it was climate change and we needed to protect against the next Sandy and that was all we need to focus on,” Orton told Yahoo News.

Orton, who is on the New York City Panel on Climate Change, said New York has plans to erect higher barriers in the short term to stop smaller floods, such as a sea wall along the eastern shore of Staten Island. But he wishes that those kinds of projects received more attention.

“When you want to build your waterfront up by 10 feet around Red Hook, that’s going to take a lot of time and effort. There’s a program called Raising Shorelines, which is really excellent. These programs should already be built as far as I’m concerned. They’re not, because so much attention has been placed on preventing the next Sandy,” he said.

According to Orton, Hoboken and the Meadowlands have smaller projects to handle these 20-year floods but they deserve additional attention throughout New Jersey.

“There’s too high of a probability of it happening if you sit around trying to do bigger things for 10 years and you don’t make sure you have a comprehensive plan for the smaller event too,” he said.

Part VII: The outlook

When asked about climate denialism in the executive branch, Bavishi said New York needs the federal government to do its part in combating climate change and thinks that denigrating science constitutes an “abdication of responsibility.”

“New York is not waiting for Washington, D.C., to address the impacts of climate change. We are moving forward with our $20 billion resilience plan and we’ll continue to advance efforts to protect the city,” she said.

According to Orton, the forecasts for Sandy were accurate but failed to make it clear how devastating the storm surge would be. Now, ensemble forecasts and cooperative storm-surge models will give the public a better idea of the dangers.

“Another Sandy? No, we’re not ready. We’d be better off. I can’t say how much less damage there would be. But we are certainly better off than we were when Sandy hit,” Orton said.

One of the challenges is we don’t know what’s coming. Most New Yorkers were taken by surprise by Sandy. Last August, Houston wasn’t prepared for 60 inches of rainfall from Hurricane Harvey.

“Everything that we’ve built to guard against another Sandy, very little will protect us from the kind of storm that Harvey was,” Freudenberg said. Despite our many investments, he continued, there’s no way the region will be completely “Sandy-proof.”

“After all that, there’s still a tremendous amount of work to do to make us Sandy-proof. It’s very difficult to make the kinds of investments and changes that need to be made to protect us, because we’ve built in places that are essentially at the front lines of climate change. As these things get worse, we’re going to have to do more than just recover and rebuild. We’ll have to change the way we do things. We’re better off than we were before Sandy, but there’s still a long way to go.”

Read more from Yahoo News:

‘That’s ridiculous’: Key Obama adviser dismisses Trump’s ‘Spygate’ claim

Judge in Michael Cohen case admonishes Michael Avenatti over his ‘publicity tour’

Study on hurricane casualties fuels talk of statehood for Puerto Rico

Bai: ‘Roseanne’ shows what the media got wrong about Trump voters

Detroit’s mayor takes on gentrification as his city bounces back from bankruptcy